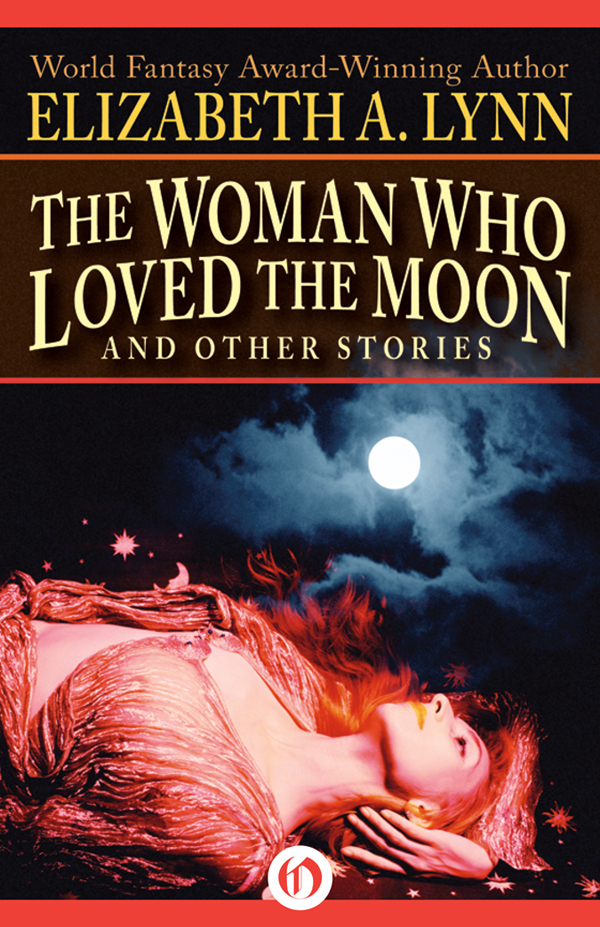

Woman Who Loved the Moon

Read Woman Who Loved the Moon Online

Authors: Elizabeth A. Lynn

Elizabeth A. Lynn

The author would like to thank the two people most responsible for the appearance of this collection: Winifred N. Lynn and Robert W. Shurtleff.

This book is for Richard Curtis

Wizard’s Domain

This story is first in the collection, although it was published in 1980, because it is the first piece of fiction I completed. Before this, everything I began ended in the middle. I was living in Chicago; it was 1971. I can still recall the sense of intense satisfaction that filled me when I wrote the final sentence and realized that yes, it was done. I started submitting the story to markets in 1972. It was rejected everywhere for four years. (Ted White lost it.) In 1977 David Hartwell accepted it for

Cosmos,

but the magazine folded before it could appear.

It had gone through several rewrites by this time. In 1979 Ellen Kushner, then assistant editor at Ace, read it and liked it. After requesting some revisions, which were made, she bought it for the fantasy anthology

Basilisk.

It is a story about power, and is set in the imaginary country of Ryoka.

* * *

They tell this story in the Eastern Counties of Ryoka. The house by Kameni Bay is gone, covered by the restless sand. If Shea Sealord lives, he is old, and his power gone. But the bay remains, gray and cold. Froth-white curls rise from it and ride to shore again, and again. Wind whips the surface of the vagrant sea, and if you stand on the rocks that breakwater the bay, you will hear that it does, indeed, make the sound of a man sobbing.

At the time of the making of this tale, there were wizards in Ryoka, greater wizards and lesser. Some had names that folk could say. Others were nameless. Some lived in caves, and fields, and mountains. And some lived in houses, wearing the guise and speaking the language of mortals. One of these was Shea. No one is quite sure when he first appeared, riding his ship

Windcatcher,

sailing up to the harbor in Skyeggo, not tall, not small, a silent man dressed in gray. He built a house on the shore of Kameni Bay, and hired servants to tend it, and commissioned a ship to be built in Skyeggo harbor, and when it was built he hired sailors to sail it. He paid in gold that did not melt. The ship sailed south, and there were those that swore it would not return. But when it did, laden with spice and timber and silver ore and all manner of precious things, the whispers ceased. When Shea built a second ship, and a third, the merchants of Ryoka wondered. The second ship sailed, and the third, and they both returned. In this manner Shea Sealord drew people to his service, and they say few regretted it. Thieves and knaves found no place with him, but honest folk were well-rewarded. In time there were a few such folk who could, if asked, call Shea “friend.”

One of these was Rhune. He had captained the first ship, not knowing where he was going or what he would find, trusting the word of the wizard. (What he found, in the southern lands, is not a part of this tale.) He was a big man, silent, slow to anger, but feared on the docks for his skill in combat. He was often seen walking through the city or on the shore of Kameni Bay with Shea. No one on the docks was surprised when Shea named him master of his fleet.

But one autumn Rhune was gone—vanished overnight, they said—and it was whispered through the city that he had somehow offended his wizard master, and had paid an unnameable and terrible penalty for that offense. Folk said he was dead, or worse, that he was not, but prisoned somewhere, in some hell known only to magicians. The whispers swelled until they seeped through the Eastern Counties. But they stopped wherever Shea turned his cool, sea-gray eyes. Folk learned not to say Rhune’s name where the Sealord might hear it, and Birne, another of Shea’s captains, was named the new master of the fleet.

But memories fade, and human loyalties are fickle. New tales filled the marketplace and docks of Skyeggo. One autumn afternoon Shea said to his servants: “I shall be walking by the bay. Do not disturb me.” And the servants bowed, and did not wonder at the order, for they had heard it many times, though (to tell the truth) not so often of late.

Shea walked to the edge of the sand. He watched the rush and retreat of the waves. They swirled around him, never touching him, always leaving him a clear space in the wet sand. He stepped forward. They retreated.

He spoke aloud. “Rhune?”

In his mind the water answered.

Come to gloat, Shea? Does it give you satisfaction to know me imprisoned here?

Shea said nothing, but he gestured with one hand. The sea changed. The wind stormed and sang and scraped the waves. They flung themselves against the rocks.

He calmed them. “You are still angry.”

Have I not cause?

cried the voice only he could hear.

“Had I not cause?” Shea responded.

A long time passed before the answer came into his mind.

You had cause.

Shea half-smiled. “Rhune, would you be free?”

Silence.

“You will never ask it, though,” he said softly. “I know you. Will you buy it from me. Rhune? I will free you now, for a price.”

What price?

“I need your help.”

My help?

“I need your skills, and your strength. I need your knowledge of men. I need your guile, my traitor, and your deceit.”

The water sobbed. For a long time there was no reply. Finally the words came.

I will help you, Lord.

Shea smiled truly, and lifted his hands to call the winds.

In the bay, a great whirlpool of water rose, like dark and liquid smoke, sucked out of the ocean by the wind. It was huge, and black. It sank lower, and lower. When it reached the height of a tall man a head emerged from it, and when as it sank further there appeared shoulders, chest, waist, until a naked man stood knee-deep in the waves. Slowly he waded to shore. He was tall and broad, with fair hair that fell past his shoulders. He was breathing hard, and shivering.

Shea took off his gray cloak, and swung it over those muscular shoulders. “Come.”

Together, neither looking back, they walked across the beach to the house.

* * *

The morning sun came through the eastward windows: also came in the sound of the sea. Rhune sat by the window, listening to the sound of the waves. He had not heard that sound for a year: the sea does not hear its own music.

There were clothes laid out for him at the foot of the bed. He remembered, with some amusement, the look on the faces of the servants when he walked into the house, naked, dripping. Shea had given a few orders and vanished into the back of the house. Servants, all of whom he knew, brought Rhune a towel, clothing, food. He had almost forgotten the taste of bread, the feel of silk.

With sunlight streaking the colored floor tiles, he dressed now and went out through the terrace doors to find the master of the house. As he had expected, Shea was sitting on the beach.

The Sealord turned as Rhune padded across the sand. “Good morning,” he said politely. “Did you sleep well?”

Rhune smiled. “Yes. Thank you.” Quietly he settled himself beside the wizard.

Shea said, “Your reappearance has somewhat shaken my household.”

“Where did they think I was?” Rhune asked.

“They do not think about such things,” said the wizard.

Rhune looked down at his hands. They were no different than when he had last seen them, a year back. As I should not have thought about wizardry and the things of wizardry, he thought.

He held his anger silent, and said, “They are wise. I’m sure the sailors and captains on the docks will be equally surprised.”

“I did not bring you back to be captain, or sailor,” said Shea.

“Why did you bring me back?” said Rhune.

Shea said, “To be a warrior, To join me—if you will—in a task of great import and high adventure.”

Rhune cocked his head and glanced at the wizard somewhat quizzically. Shea was not wont to speak dramatically, except in jest. But the gray, changeful eyes were serious. Shea pointed at the water.

“Look,” he said.

Rhune looked at his prison, and saw a volcano, all green and gray and moving, rise from the waves, spewing wet fire.

It fell into the bay again, and the waves made by the fall surged up the beach, detouring around the two seated men.

“Of what does that remind you?” said Shea.

Rhune said slowly, “That’s easy. The Firemountain.”

Four days’ journey off Ryoka coast the great volcano sat. It was ruled by the Firelord, Seramir. The volcano lay quiescent now, its fire seeming spent. Yet once Seramir had been very powerful. Seventy years back his ships had sailed from the Firemountain, black ships with red sails and brightly painted dragons on their bows. Grim men with weapons had tramped from the ships to strip the wealth and beauty from the towns of the eastern shore.

Khelen the Sorceress, greatest magician of her day, had come from the west to pit magic against magic. Tales of that battle are still told from one end of Ryoka to the other. It was a terrible fight. But Khelen prevailed. Ships smashed, men beaten, drowned, or buried, Seramir had begged peace. By the terms of that peace he was confined to the Firemountain, forbidden to sail or to cause others to sail beyond a day’s journey from its shores.

Yet he was still feared in the coastal counties. People spoke with fear of the red-eyed lord of fire. And trading ships sailing to and from Skyeggo paid a toll in gold to the captains of the tall dragon ships.

“The Firemountain, yes,” said Shea. “Where Seramir Firelord lives, and watches—and hates.”

“Hates?” said Rhune, who knew something of hatred.

“Hates—the land, its cities, its people. He ages now. His power wanes, and so he loves it more, and craves its increase. Yet the only power he has over all Ryoka is the power of the toll—he who is lord of Fire! It galls him. He does not need gold, what is gold to a wizard? I can make gold out of sand. So can he. He craves mastery.”

The certainty in Shea’s voice made Rhune shiver. “Is he mad?” he asked.

“A little. Even magicians were born human.”

I can understand him, then, Rhune thought. I was mad, once. “You spoke of war,” he said. “I thought, when Khelen bested him, Seramir swore never to make war upon Ryoka again.”

“He swore never to send ships or men to bum cities and plunder the land. He keeps that oath. Only”—Shea shifted, and sand slid down the side of the dune—”it seems that the fires of earth itself have of late grown restless. From all over Ryoka, out to the very edge of the Western Counties, come reports of crevices opening in the earth, rocks shifting and falling, streams steaming. The cliffs at Mantalo erupted a month ago, drowning ships and men in spouts of liquid fire. Forty died. A little firemountain grows now in the harbor.”

Rhune remembered the harbor of Mantalo, blue and white and gold, filled with tall-masted ships bobbing in the sun. A horror filled him. “Seramir has done this?”