Women's Bodies, Women's Wisdom (103 page)

Read Women's Bodies, Women's Wisdom Online

Authors: Christiane Northrup

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #Personal Health, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Specialties, #Obstetrics & Gynecology

Gayle Peterson, in her book

Birthing Normally,

points out that women labor in the same way they live. Labor is a crisis situation for most women. They approach it the way they approach any crisis: Some believe they are powerless, while others try to assume control. A study of the differences between women who had chosen to induce labor and those who had chosen to let labor come spontaneously showed that those who chose induction lacked trust in their own reproductive systems. They were more likely to complain during their menstrual periods, had more complications in their obstetrical history, and had more anxiety about going into labor.

49

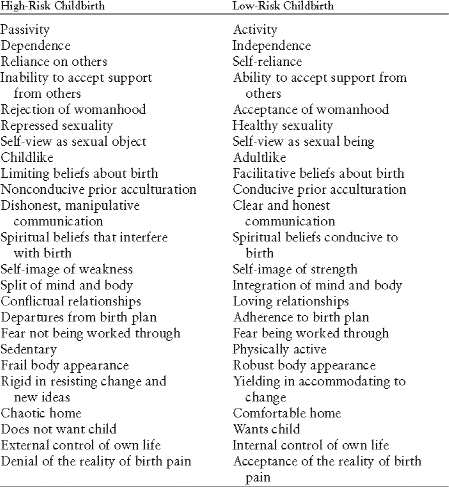

Gayle Peterson and Lewis Mehl-Madrona did a study of pregnant women in which they were able to predict with 95 percent accuracy which of them would get into trouble during labor based on the criteria in table 7, which is supported by the many stud ies on individual complications.

50

T

HE

C

ERVIX

I

S A

S

PHINCTER

Midwife Ina May Gaskin coined the term “Sphincter Law” to explain why so many women’s labors stop progressing the minute they get to the hospital and why so many experience “failure to progress” and end up with interventions. The reason is that the cervix is a sphincter—just like the ones that control urination and elimination. It’s impossible to let go and relax a sphincter unless you feel totally relaxed and safe. That’s why so many people get constipated when they travel.

P

OTENTIAL

R

ISK

F

ACTORS IN

C

HILDBIRTH

“Rescuing” Women from Labor

Not uncommonly, a woman in labor will demand that her partner do something to “rescue” her from the situation she’s in. How well I remember husbands whose wives sought out their support during their contractions by crying something like “Jer-ry—

do

something!” These men then yelled at me and said, “How much longer is this going to go on? You’d better take care of this soon, or you’re going to hear from me.” I’ve been threatened repeatedly by husbands who wanted me to “fix” their wives’ labors as soon as possible— or else!

Unable to control their wives’ discomfort, and angry at their own feelings of helplessness in a process about which they can do nothing, these men become abusive to the obstetrician—“End this misery!” Their wives, unable to continue their usual roles as male emotional shock absorbers, watch helplessly or expect their husbands to play their Mr. Fix-It roles. These women become even further out of touch with themselves. Labor is

not

an ideal time to educate a couple about transformative experiences. However, if a couple can be encouraged between contractions simply to stay with the process, understanding that it is normal and natural and not life-threatening, then sometimes they can be helped to work

with

the contractions and the process of labor, and not against them. My associate Bethany Hays, an obstetrician-gynecologist and medical director of the True North Health Center in Falmouth, Maine, reminds husbands or partners that they can’t have the baby for their mates, nor can they take away the pain. But what they can do is love their partners. This is a very big gift for most women in labor—simply to feel loved through the entire process. Women who are totally supported in labor emotionally and physically have the op portunity to be transformed forever by the knowledge that they

were

able to go through with it, that they have the inner resources after all. Every woman deserves this loving support—and studies show that such women are more loving with their children as a result. Labor lasts a relatively short time. Yet it’s powerful enough to transform a woman’s entire relationship with her body and its processes. After having her baby normally, one woman told me, “I have never felt so powerful in my whole life. I was so energized by the process. I was flying. I wanted to call everyone I knew and share my joy with them.”

Reversing a lifelong pattern of coping behavior during labor, how ever, is not always possible. When I was still delivering babies, I found that no amount of cajoling, education, or pleading on my part could reverse many women’s inherited belief that they

cannot

give birth normally, that they must have drugs and anesthesia to do it.

The medical system participates fully in treating childbirth as an emergency needing a cure. Because of its patriarchal nature, the med ical system too often becomes the symbolic “husband” for all the women crying “Jerry,

do

something!” And believe me, doctors are trained in many ways to “do something.” Each of our doings has a price. Some studies show, for instance, that epidural anesthesia increases the rate of cesarean section because this anesthetic relaxes the pelvic floor muscles, causing the baby to engage with the head in what’s called the occiput posterior position—facing up. It’s much harder to push a baby out when he or she is in this position; it also slows down the process and may add to the baby’s distress. Epidurals are also a metaphor for our current mind-body split approach to childbirth: “I want to be awake and intellectually aware, but I don’t want to feel my body.” This was illustrated recently when a family practitioner friend of mine was attending the delivery of a woman with an epidural who was almost ready to give birth. She was watching a soap opera on TV and completely unaware of anything going on below her waist. At the point when the baby was crowning and actually being born, she asked my friend, the delivering physician, to please move out of the way so that she could see the TV screen. Though the epidural is not the villain here, it clearly made it much easier for this new mother to stay out of touch with her baby and her birth process—and also made the new mother much less aware of her newborn baby than she otherwise would have been. Pain medications also cross the placenta and may af fect the baby. Forceps, episiotomies, vacuum extractors, oxytocin augmentation of labor, and unnecessary cesarean sections are other interventions that are not without risk.

A woman has the power within to birth normally and needs to know that drugs and anesthetics have potential adverse side effects. When I was delivering babies, I was frustrated by women who had no intention of delivering normally, and I tried to change them through education. But this was

my

problem, not necessarily theirs. They wanted all the technology that the hospital could offer. I now realize that it was not my job to change them or anyone else. Each woman must look inside and see where she is—and be as honest with herself as possible. My job is to present alternatives in every situation and let each woman choose.

Fetal Monitors and Cesarean Sections

There is no more striking example of the overuse of technology in childbirth than the high cesarean section rates at many U.S. hospitals, a result of the medicalization of childbirth, fueled by fear of lawsuits if a baby is not perfect. Although the cesarean section rate in most teaching hospitals is now 33 percent, in some cities a white woman with insurance has a 50 percent chance of having a cesarean.

51

During my residency training, when fetal monitoring hit the scene and the cesarean section rate began to soar, I remember thinking, “How can it be that such a large percentage of women aren’t able to go through a normal physiological event without the aid of anesthesia and major surgery? How could the human race possibly have survived if this many women really need major surgery to give birth? What is going wrong here?”

I was taught that I must treat everyone as though she was going to have a potential complication, as if a normal labor could turn into a crisis at a moment’s notice. Whenever a woman arrived in labor, we immediately put in an intravenous line, drew blood, ruptured her membranes (broke the amniotic sac, or “bag of waters” surrounding the baby), screwed a fetal scalp electrode into the baby’s head, and threaded a catheter into her uterus to measure intrauterine pressure on the fetal monitor. Then she and her family, the doctors, and the nurses all fixed their gazes on the monitor and pretty much relied on

it

to tell us what to do next. The woman was asked to labor in the position that gave the best monitor tracing—not the one that felt best to her. I recall trying to get these monitoring devices even into women whose babies were about to be delivered when they came through the door. If I didn’t have a monitor strip for documentation and there was a bad outcome, I knew that I would be in trouble with my attending physician. So of course I performed all these procedures, including breaking the amniotic sac, even though during my second year of residency, I had gone to a meeting of the International Childbirth Education Association (ICEA) and learned that babies whose mothers’ membranes have been artificially ruptured show evidence of more stress in utero—the pH of their scalp blood sam ples is lower. I also learned at this meeting that the amniotic fluid is the best “packing material” available. It cushions the baby’s body during contractions. Why were we so eager to mess with nature’s protection? So that we could put in our technological monitors!

Is it any wonder that when you hook up a vulnerable laboring woman to three or four different tubes and wires and then rupture her membranes, she, and subsequently her baby, might get a little scared—resulting in some fetal distress? To make matters worse, there’s something about that monitor screen that draws everyone’s attention to it—and away from the laboring woman. So despite the data showing that it’s not really helping, the hospital staff and the laboring woman herself all pay more attention to the monitor screen than to the mother’s own internal experience. Technology designed to help has actually succeeded in cementing a mind-body split in place.

Later, studies would show that electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) does not actually improve perinatal outcome when compared with a nurse listening to the heart rate periodically.

52

What it does do is increase cesarean section rates—a great example of technology catching on before all the data were in. George Macones, M.D., who headed up the development of the latest fetal monitoring guidelines for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, summarized it quite nicely: “Since 1980, the use of EFM has grown dramatically, from being used on 45% of pregnant women in labor to 85% in 2002. Although EFM is the most common obstetric procedure today, unfortunately it hasn’t reduced perinatal mortality or the risk of cerebral palsy.” (Back when fetal monitoring was introduced, cerebral palsy was thought to be related to obstetrical trauma. Hence, obstetricians were blamed for it. Subsequent large-scale studies have now proven that cerebral palsy results from in utero neurologic damage that happens long before labor and birth.) “In fact, the rate of cerebral palsy has essentially remained the same since World War II despite fetal monitoring and all of our advancements in treatments and interventions.”

53

A survey of 1,600 women conducted by Harris Interactive for the nonprofit Maternity Center Association showed that 61 percent experienced between six and ten medical interventions during their labor and deliveries, including being hooked up to an IV and being given Pitocin to speed labor— which makes contractions more painful and increases the risk of fetal distress and neonatal jaundice. (In addition, 43 percent had between three and five major interventions—including induction, episiotomy, C-sections, and forceps delivery—and eight out of ten women, including 91 percent of first-time mothers, had pain relief medication during labor.)

Many cases of fetal distress could potentially have been reversed by soothing the mother and asking her to focus inside on how her baby is and send it messages of reassurance. Biofeedback has documented the profound effects of thoughts on body systems such as blood pressure, pulse, and skin resistance. The baby is

part

of a woman’s body. Her thoughts and emotions can and do have large effects on her baby.

Many obstetricians feel inherently that vaginal delivery is just plain dangerous, leading to increased fetal trauma. I’ve been in discussions with male and female colleagues who believe on some very deep, prob ably unexamined level that abdominal delivery is the superior mode of arrival. Recently some are strongly advocating elective cesareans as a matter of preference.

Unfortunately, you have to be quite resilient and self-assured to resist the environment of inductions and planned C-sections that is now common in far too many hospitals. The newly pregnant daughter of one of my friends went to a hospital in Texas for her first prenatal visit. The doctor asked, “Would you like to schedule an induction or a C-section?” The idea of going into spontaneous labor was simply not entertained. Another young woman I know was told that the skin on her vagina was “too thin” to withstand a vaginal delivery and that a vaginal birth might result in tears. The doctor then scheduled a C-section for her. How could one possibly suggest major abdominal surgery (talk about tears!) as a preventative for a possible vaginal laceration that could be easily repaired? And more important, how have we women become so brainwashed about labor that we simply go along with this?