Wonder Woman Unbound (35 page)

Read Wonder Woman Unbound Online

Authors: Tim Hanley

This kind of revision was common among believers in originary matriarchy. Discussing the liberal feminist focus on past matriarchies, Joanne H. Wright states that this past offered “a glorified image of woman on which a new identity could be based.” She continues:

The new identity being forged has little to do with past matriarchy, but is rather a construction, one which is then read back into the past and sanctified for the future.

In the few snippets of myths and ancient history that referred to female rule, liberal feminists built a history of universal matriarchy that reflected, and in turn legitimized, their own values. The details of the actual past were revised or, as Wright says, sanctified to allow the modern values to shine through.

Steinem and her friends did the same with Wonder Woman. They transferred their own values onto the original Wonder Woman stories, creating a historic icon that reflected their own beliefs instead of accurately depicting her original feminism. They were interested in the similarities between Wonder Woman and themselves, not the differences. As such, their image of the Golden Age Wonder Woman was based on selective readings and, at times, inaccurate discussions of the character’s history.

One of the ways the original Wonder Woman was reconciled with modern values was by downplaying parts of the comics that a modern audience might find offensive. Coming on the heels of the civil rights movement, the women’s liberation movement was very concerned with racism. Like most comic books in the 1940s,

Wonder Woman

often portrayed nonwhite characters in stereotypical and racist ways. Case in point: the sinister Japanese soldiers Wonder Woman regularly faced, with their savage appearance and exaggerated dialogue, like: “So the gr-reat

Wonder Woman

is-ss pris-soner at las-st! Will be pleas-sure to s-see you die s-sslowly!”

Steinem and Edgar both addressed the problem, with Edgar mentioning “the distorted and villainized Nazis and Japanese” and Steinem discussing “highly jingoistic and even racist overtones.” However, this was quickly tempered with excuses. Steinem put the blame on the artist, writing that “Wonder Woman’s artists sometimes fell victim to the patriotic atmosphere of World War II.” After discussing the problematic art of these stories, Steinem began the next paragraph by stating that “compared to the other comic book characters of the period, however, Wonder Woman is still a relief.” While they acknowledged the problems, the immediate downplaying swiftly brushed them aside as inconsequential.

It was a similar situation with Wonder Woman’s nationalism and participation in the war effort. With America in the midst of the wildly unpopular Vietnam War, peace and nonviolent conflict resolution were prevalent trends. Again, Steinem acknowledged Wonder Woman’s involvement in the war, writing that “some of the Wonder Woman stories preach patriotism in a false way,” and that these stories contained “superpatriotism.” However, she downplayed these problems by arguing that “much of the blame rests with history” and “a nation mobilized for war is not a nation prepared to accept criticism.”

However, Wonder Woman fought in World War II more than any other DC Comics superhero, both on the front lines as Wonder Woman and in the defense department as Diana Prince. Many in the 1970s were upset about a war in Vietnam to depose a leader with anti-American beliefs, but Wonder Woman did that often in the 1940s. She regularly ousted local leaders across the globe who worked with the enemy or promoted un-American ideals, replacing them with American-style democracies and leaders who supported the Allies. The Golden Age Wonder Woman was more than patriotic; she was a bona fide agent for the American military, fighting its wars and spreading its values.

After running through the potentially problematic aspects of Marston’s Wonder Woman, Steinem wrote that “all these doubts paled beside the relief, the sweet vengeance, the toe-wriggling pleasure of reading about a woman who was strong, beautiful, courageous, and a fighter for social justice.” Troublesome aspects of the past could be downplayed because there were so many better things to talk about. To be fair, the degree of racism in early Wonder Woman comics is debatable and her superpatriotism, however prevalent, really wasn’t the main point of the character. However, this tendency to dismiss parts of Wonder Woman’s past put Steinem and her friends on a slippery slope to missing Marston’s message entirely.

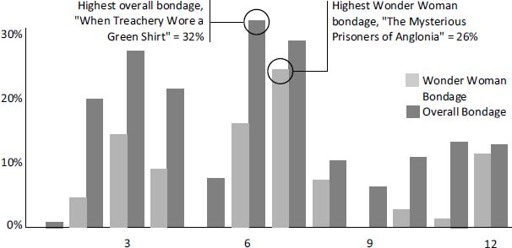

Racism and superpatriotism were at least mentioned before being downplayed, but there was no discussion of bondage in any of the celebratory Wonder Woman articles, despite the fact that there was a fair bit of bondage in the

Ms. Wonder Woman

book. Overall, 15 percent of the panels in the book had bondage imagery. The chart above also shows some impressive individual numbers, with someone tied up in 32 percent of the panels in “When Treachery Wore a Green Shirt” and Wonder Woman herself tied up for 26 percent of “The Mysterious Prisoners of Anglonia.”

The

Ms. Wonder Woman

book well represents Marston’s use of bondage, ranging from the fun binding games of Paradise Island with Wonder Woman tied to a pole to the brutality of Dr. Psycho ripping the soul from her body and chaining it to a wall.

*

Even though they didn’t directly address bondage, Steinem and her group nonetheless showcased it, but omitting bondage from their discussion led to ignoring submission as well. The heart of Marston’s feminist theories, submission was the thread that connected nearly everything he ever wrote. He was an advocate of the loving authority of women and the world peace that it would bring, but no one mentioned submission, DISC theory, or his utopian vision of the future.

This omission may have been intentional. Both Steinem and Edgar quote Marston’s distaste for the “blood-curdling masculinity” of other superhero comics, a line from an article he wrote for the

American Scholar.

In the next paragraph of that very article, Marston talked about the appeal that a strong heroine had for boys, writing, “Give them an alluring woman stronger than themselves to submit to and they’ll be

proud

to become her slaves!” Neither Steinem nor Edgar brought up that bit.

Having left out bondage and submission, there was no groundwork laid for Marston’s message of female superiority. Steinem saw traces of such a message but was unsure about it. She wrote that “females were sometimes romanticized as biologically and unchangeably superior” and that the comics “hint that women are biologically, and therefore immutably, superior to men,” but “sometimes” and “hints” are hardly strong terms. Ultimately, Steinem asked incredulously, “Is the reader supposed to conclude women are superior?”

The answer, of course, is yes. That was the entire point. The superiority of women was the core message of the book, and Steinem kept missing it. She concluded that Wonder Woman was so busy stopping bad guys and saving the world that she “rarely has the leisure to hint at what the future social order ought to be,” but the entire purpose of Wonder Woman comics was to prepare young readers for the inevitable coming matriarchy. It was squarely focused on the future social order, and everything Marston said about his comics reinforced that point.

An important component of this disconnect between Marston and

Ms.

was who they believed the book was for. Marston was writing for boys, to get them used to strong, loving women and to prepare them for the transition to matriarchy. For Steinem, Chesler, and Edgar, however, Wonder Woman was meant to be for girls.

The most prominent theme that ran through all three women’s essays was that Wonder Woman was a role model for female readers. Reflecting on reading Wonder Woman comic books as a young girl, Edgar asked, “Who could resist a role model like that?” Chesler wrote that “the comic also underlines the importance of successful female role models in teaching women strength and confidence.” A huge portion of Steinem’s essay was about reading Wonder Woman comics as a young girl and how much Wonder Woman meant to her growing up. She called Wonder Woman a “version of the truisms that women are rediscovering today: that women are full human beings; that we cannot love others until we love ourselves; that love and respect can only exist between equals.” When Steinem put Wonder Woman on the first cover of Ms. and adopted her as a feminist icon, it wasn’t because the mod Diana Prince desperately needed some feminism. It was because women and girls needed the Amazon Wonder Woman as a role model. As originary matriarchy shows, liberal feminists were always in search of a feminist past; with Wonder Woman they found an established role model who could be a symbol for everything they were trying to become.

Steinem listed the values that Wonder Woman represented; not surprisingly, they were the core tenets of liberal feminism:

- “Strength and self-reliance for women”

- “Sisterhood and mutual support among women”

- “Peacefulness and esteem for human life”

- “A diminishment both of ‘masculine’ aggression and of the belief that violence is the only way of solving conflicts”

Sisterhood and self-reliance were especially emphasized in the

Ms. Wonder Woman

book. The largest section of the book was titled “Sisterhood,” and in her preface Steinem wrote that “Wonder Woman’s final message to her sisters almost always contained one simple and unmistakable moral: self-reliance.” Which is true. However, Marston’s focus on self-reliance was because women were superior and could do a better job than men. For Steinem and her friends, self-reliance was a key part of their belief in self-improvement. It was to make them less dependent on men, not to ready them to take over the world.

This association of Wonder Woman with the liberal feminist focus on self-improvement caught on quickly. For example, in the July 1973 issue of

Sister: The Newspaper of the Los Angeles Women’s Center,

a cartoon showed Wonder Woman snatching a speculum from a male doctor and announcing, “With my speculum, I

am

strong! I

can

fight!” Taking control of your sexual health was an important principle in liberal feminist self-reliance, and Wonder Woman was right there, a role model leading the way.

Self-reliance and sisterhood were important components of Marston’s Wonder Woman as well. The liberal feminist version of Wonder Woman wasn’t a radical reinterpretation of the character; she was a modern update, building on certain aspects of the old while setting aside others. Compared to Kanigher’s Wonder Woman or the mod Diana Prince, this incarnation of the character probably had the most in common with Marston’s vision.

It’s quite impressive that Steinem and company were able to translate Marston’s particular feminism into something that resonated with a modern audience. It was a fascinating evolution of the character, and one that made Wonder Woman relevant for the first time in decades. While it may have been an inaccurate depiction of Marston’s Wonder Woman, what’s more significant is that Wonder Woman meant so much to these women and that they were able to remake her into a massively popular feminist icon. Authorial intent is important, but writing isn’t a one-way street. What resonates with readers and what they see in a character is just as relevant, and Steinem and her friends saw a fantastic role model in Wonder Woman.

However, one problem remains: the articles were written as if these liberal feminist beliefs were Marston’s actual intent. They celebrate the “original” Wonder Woman but are fairly inaccurate in that respect. What’s happened since is that the

Ms.

take on Wonder Woman has overwritten Marston’s actual intent for Wonder Woman.

The

Ms. Wonder Woman

book has been the premier resource for the history of Wonder Woman for some time. For decades, there was nowhere else to see the old comics, and Marston’s other writings were largely unknown. As such, the articles by Steinem and her friends are often viewed as definitive accounts of the early years of Wonder Woman. This cleaned-up, role-model Wonder Woman has become the only Wonder Woman. Much like Steinem and her friends read Wonder Woman comics through the lens of their own feminism, many since have read the same comics through the lens of Steinem. Marston’s brand of feminism is largely forgotten, and it is often quickly dismissed or downplayed when it comes up.

Epic Comic Book Fail