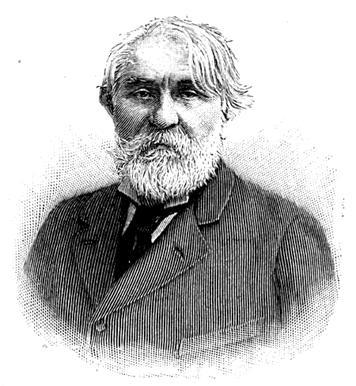

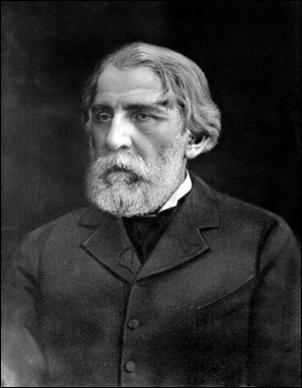

Works of Ivan Turgenev (Illustrated) (394 page)

Read Works of Ivan Turgenev (Illustrated) Online

Authors: IVAN TURGENEV

Calmly and gracefully thou movest along the path of life, tearless and smileless, and scarce a heedless glance of indifferent attention ruffles thy calm.

Thou art good and wise … and all things are remote from thee, and of no one hast thou need.

Thou art fair, and no one can say, whether thou prizest thy beauty or not.

No sympathy hast thou to give; none dost thou desire.

Thy glance is deep, and no thought is in it; in that clear depth is emptiness.

So in the Elysian field, to the solemn strains of Gluck’s melodies, move without grief or bliss the graceful shades.

November 1879.

Stay! as I see thee now, abide for ever in my memory!

From thy lips the last inspired note has broken. No light, no flash is in thy eyes; they are dim, weighed down by the load of happiness, of the blissful sense of the beauty, it has been thy glad lot to express — the beauty, groping for which thou hast stretched out thy yearning hands, thy triumphant, exhausted hands!

What is the radiance — purer and higher than the sun’s radiance — all about thy limbs, the least fold of thy raiment?

What god’s caressing breath has set thy scattered tresses floating?

His kiss burns on thy brow, white now as marble.

This is it, the mystery revealed, the mystery of poesy, of life, of love!

This, this is immortality! Other immortality there is none, nor need be.

For this instant thou art immortal.

It passes, and once more thou art a grain of dust, a woman, a child…. But why need’st thou care! For this instant, thou art above, thou art outside all that is passing, temporary. This thy instant will never end. Stay! and let me share in thy immortality; shed into my soul the light of thy eternity!

November 1879.

I used to know a monk, a hermit, a saint. He lived only for the sweetness of prayer; and steeping himself in it, he would stand so long on the cold floor of the church that his legs below the knees grew numb and senseless as blocks of wood. He did not feel them; he stood on and prayed.

I understood him, and perhaps envied him; but let him too understand me and not condemn me; me, for whom his joys are inaccessible.

He has attained to annihilating himself, his hateful

ego

; but I too; it’s not from egoism, I pray not.

My

ego

, may be, is even more burdensome and more odious to me, than his to him.

He has found wherein to forget himself … but I, too, find the same, though not so continuously.

He does not lie … but neither do I lie.

November 1879.

What an insignificant trifle may sometimes transform the whole man!

Full of melancholy thought, I walked one day along the highroad.

My heart was oppressed by a weight of gloomy apprehension; I was overwhelmed by dejection. I raised my head…. Before me, between two rows of tall poplars, the road darted like an arrow into the distance.

And across it, across this road, ten paces from me, in the golden light of the dazzling summer sunshine, a whole family of sparrows hopped one after another, hopped saucily, drolly, self - reliantly!

One of them, in particular, skipped along sideways with desperate energy, puffing out his little bosom and chirping impudently, as though to say he was not afraid of any one! A gallant little warrior, really!

And, meanwhile, high overhead in the heavens hovered a hawk, destined, perhaps, to devour that little warrior.

I looked, laughed, shook myself, and the mournful thoughts flew right away: pluck, daring, zeal for life I felt anew. Let him, too, hover over me,

my

hawk…. We will fight on, and damn it all!

November 1879.

Whatever a man pray for, he prays for a miracle. Every prayer reduces to this: ‘Great God, grant that twice two be not four.’

Only such a prayer is a real prayer from person to person. To pray to the Cosmic Spirit, to the Higher Being, to the Kantian, Hegelian, quintessential, formless God is impossible and unthinkable.

But can even a personal, living, imaged God make twice two not be four?

Every believer is bound to answer,

he can

, and is bound to persuade himself of it.

But if reason sets him revolting against this senselessness?

Then Shakespeare comes to his aid: ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,’ etc.

And if they set about confuting him in the name of truth, he has but to repeat the famous question, ‘What is truth?’ And so, let us drink and be merry, and say our prayers.

July 1881.

In days of doubt, in days of dreary musings on my country’s fate, thou alone art my stay and support, mighty, true, free Russian speech! But for thee, how not fall into despair, seeing all that is done at home? But who can think that such a tongue is not the gift of a great people!

June 1882.

THE END OF PROSE POEMS

ARKADY SERGEYITCH ISLAYEV, a wealthy landowner, aged 36.

NATALYA PETROVNA, his wife, aged 29.

KOLYA, their son, aged 10.

VERA, their ward, aged 17.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA ISLAYEV, mother of Islayev, aged 58.

LIZAVETA BOGDANOVNA, a companion, aged 37.

SCHAAF, a German tutor, aged 45.

MIHAIL ALEXANDROVITCH RAKITIN, a friend of the family, aged 30.

ALEXEY NIKOLAYEVITCH BELIAYEV, a student, Kolya’s tutor, aged zi.

AFANASY IVANOVITCH BOLSHINTSOV, a neighbour, aged 48.

IGNATY ILYITCH SHPIGELSKY, a doctor, aged 40.

MATVEY, a manservant, aged 40.

KATYA, a maidservant, aged 20.

The action takes place on Islayev’s estate.

There is an interval of one day between

ACTS I

and

II, ACTS II

and

III,

and

ACTS IV

and

V.

A drawing - room. On Right a card - table and a door into the study; in Centre a door into an outer room; on Left two windows and a round table. Sofas in the corners. At the card - table

ANNA SEMYONOVNA, LIZAVETA BOGDANOVNA

and

SCHAAF

are playing preference;

NATALYA PETROVNA

and

RAKITIN

are sitting at the round table; she is embroidering on canvas; he has a book in his hand. A clock on the wall points to three o’clock.

SCHAAF. Hearts.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Again? Why, if you go on like that, my good man, you will beat us every time.

SCHAAF

[phlegmatically].

Eight hearts.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA

[to

LIZAVETA BOGDANOVNA]. What a man! There’s no playing with him. [LIZAVETA BOGDANOVNA

smiles.]

NATALYA PETROVNA

[to

RAKITIN]. Why have you left off? Go on.

RAKITIN

[raising his head slowly],

‘Monte Cristo se redressa haletant. . . .’ Does it interest you, Natalya Petrovna?

NATALYA PETROVNA. Not at all.

RAKITIN. Why are we reading it then?

NATALYA PETROVNA. Well, it’s like this. The other day a woman said to me: ‘You haven’t read Monte Cristo? Oh, you must read it -

- it’s charming.’ I made her no answer at the time, but now I can say that I’ve been reading it and found nothing at all charming in it.

RAKITIN. Oh, well, since you have already made up your mind about it. ...

NATALYA PETROVNA. You lazy creature!

RAKITIN. Oh, I don’t mind. . ..

[Looking for the place at which he stopped.]

‘Se redressa haletant et. . . .’

NATALYA PETROVNA

[interrupting him].

Have you seen Arkady to - day?

RAKITIN. I met him on the dam.... It is being repaired. He was explaining something to the workmen and to make things clearer waded up to his knees in the sand.

NATALYA PETROVNA. He gets too hot over things, he tries to do too much. It’s a failing. Don’t you think so?

RAKITIN. Yes, I agree with you.

NATALYA PETROVNA. How dull that is!... You always agree with me. Go on reading.

RAKITIN. Oh, so you want me to quarrel with you. . . . By all means.

NATALYA PETROVNA. I want ... I want ... I want

you

to want. ... Go on reading, I tell you.

RAKITIN. I obey, madam.

[Takes up the book again.]

SCHAAF. Hearts.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. What? Again? It’s insufferable!

[To

NATALYA PETROVNA.] Natasha . . . Natasha! . . .

NATALYA PETROVNA. What is it?

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Only fancy! Schaaf wins every point. He keeps on -

- if it’s not seven, it’s eight.

SCHAAF. And now it’s seven.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Do you hear? Its awful.

NATALYA PETROVNA. Yes ... it is.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Back me up then!

[To

NATALTA PETROVNA.] Where’s Kolya?

NATALYA PETROVNA.

He’s gone out for a walk with the new tutor.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Oh! Lizaveta Bogdanovna, I call on you.

RAKITIN

[to

NATALYA PETROVNA.] What tutor?

NATALYA PETROVNA. Ah! I forgot to tell you, while you’ve been away, we’ve engaged a new teacher.

RAKITIN. Instead of Dufour?

NATALYA PETROVNA. No ... a Russian teacher. The princess is going to send us a Frenchman from Moscow.

RAKITIN. What sort of man is he, the Russian? An old man?

NATALYA PETROVNA. No, he’s young.... But we only have him for the summer.

RAKITIN. Oh, a holiday engagement.

NATALYA PETROVNA. Yes, that’s what they call it, I believe. And I tell you what, Rakitin, you’re fond of studying people, analysing them, burrowing into them. . . .

RAKITIN. Oh, come, what makes you . . .

NATALYA PETROVNA, Yes, yes.... You study him. I like him. Thin, well made, merry eyes, something spirited in his face. . . . You’ll see. It’s true he is rather awkward . . . and you think that dreadful.

RAKITIN. You are terribly hard on me to - day, Natalya Petrovna.

NATALYA PETROVNA. Joking apart, do study him. I fancy he may make a very fine man. But there, you never can tell!

RAKITIN. That sounds interesting.

NATALYA PETROVNA. Really?

[Dreamily.]

Go on reading.

RAKITIN. ‘Se redressa haletant et...’

NATALYA PETROVNA

[suddenly looking round].

Where’s Vera? I haven’t seen her all day. [

With a smile, to

RAKITIN.] Put away that book. ... I see we shan’t get any reading done to - day. . . . Better tell me something.

RAKITIN. By all means. . . . What am I to tell you? You know I stayed a few days at the Krinitsyns’. . . . Imagine, the happy pair are bored already.

NATALYA PETROVNA. How could you tell?

RAKITIN. Well, boredom can’t be concealed.... Anything else may be, but not boredom. . . .

NATALYA PETROVNA

[looking at him].

Anything else can then?

RAKITIN

[after a brief pause].

I think so.

NATALYA PETROVNA

[dropping her eyes].

Well, what did you do at the Krinitsyns’?

RAKITIN. Nothing. Being bored with friends is an awful thing; you are at ease, you are not constrained, you like them, there’s nothing to irritate you, and yet you are bored, and there’s a silly ache, like hunger, in your heart.

NATALYA PETROVNA. You must often have been bored with friends.

RAKITIN. As though you don’t know what it is to be with a person whom one loves and who bores one!

NATALYA PETROVNA

[slowly].

Whom one loves, that’s saying a great deal. . . . You are too subtle to - day. . . .

RAKITIN. Subtle. . . . Why subtle?

NATALYA PETROVNA. Yes, that’s a weakness of yours. Do you know, Rakitin, you are very clever, of course, but . . .

[Pausing]

sometimes we talk as though we were making lace. . . . Have you seen people making lace? In stuffy rooms, never moving from their seats. . . . Lace is a fine thing, but a drink of fresh water on a hot day is much better.

RAKITIN. Natalya Petrovna, you are . . .

NATALYA PETROVNA. What?

RAKITIN. You are cross with me about something.

NATALYA PETROVNA. Oh, you clever people, how blind you are, though you are so subtle! No, I’m not cross with you.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Ah! at last, he has lost the trick!

[To

NATALYA PETROVNA.] Natasha, our enemy has lost the trick!

SCHAAF

[sourly].

It’s Lizaveta Bogdanovna’s fault.

LIZAVETA BOGDANOVNA

[angrily].

I beg your pardon -

- how could I tell Anna Semyonovna had no hearts?

SCHAAF. In future I call not on Lizaveta Bogdanovna.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA

[to

SCHAAF]. Why, how is she, Lizaveta Bogdanovna, to blame?

SCHAAF

[repeats in exactly the same tone of voice].

In future I call not on Lizaveta Bogdanovna.

LIZAVETA BOGDANOVNA. As though I care! What next! . . .

RAKITIN. You look somehow different, I see that more and more.

NATALYA PETROVNA

[with a shade of curiosity].

Do you mean it?

RAKITIN. Yes, really. I find a change in you.

NATALYA PETROVNA. Yes?... If that’s so, please. . . . You know me so well -

- guess what the change is, what has happened to me . . . will you?

RAKITIN. Well. . . . Give me time. . . .

[Suddenly

KOL YA

runs in noisily from the outer room and straight up to

ANNA SEMYONOVNA.]

KOLYA. Granny, Granny! Do look what I’ve got!

[Shows her a bow and arrows.]

Look!

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Show me, darling. ... Oh what a splendid bow! Who made it for you?

KOLYA. He did ... he. ...

[Points to

BELIAYEV,

who has remained at the door.]

ANNA SEMYONOVNA. Oh! but how well it’s made. . . .

KOLYA. I shot at a tree with it, Granny, and hit it twice. . . .

[Skips about.]

NATALYA PETROVNA. Show me, Kolya.

KOLYA

[runs to her and while

NATALYA PETROVNA

is examining the bow].

Oh, maman, you should see how Alexey Nikolaitch climbs trees! He wants to teach me and he’s going to teach me to swim too. He’s going to teach me all sorts of things.

[Skips about.]

NATALYA PETROVNA. It is very good of you to do so much for Kolya.

KOLYA

[interrupting her, warmly].

I do like him, maman, I love him.

NATALYA PETROVNA

[stroking

KOLYA’S

head].

He has been too softly brought up. ... Make him a sturdy, active boy.

[BELIAYEV

bows.]

KOLYA. Alexey Nikolaitch, let’s go to the stable and take Favourite some bread.

BELIAYEV. Very well.

ANNA SEMYONOVNA

[to

KOLYA]. Come here and give me a kiss first. . . .

KOLYA

[running off].

Afterwards, Granny, afterwards!

[Runs into the outer room;

BELIAYEV

goes out after him.]