Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (10 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

In the restaurant the black waiters are dressed in white with pink sashes

and caps to match the tablecloths. So humble, so eager to please. In

England, diners are terrorised by the waiters, here vice versa.

One of them is asked to take a photo of another table. We all watch

nervously in case he doesn't know how to do it. Then, as the shutter

clicks, Yvette turns to me and says, `Easy to teach monkeys to press

buttons.' Smiling, she dares me. I smile back.

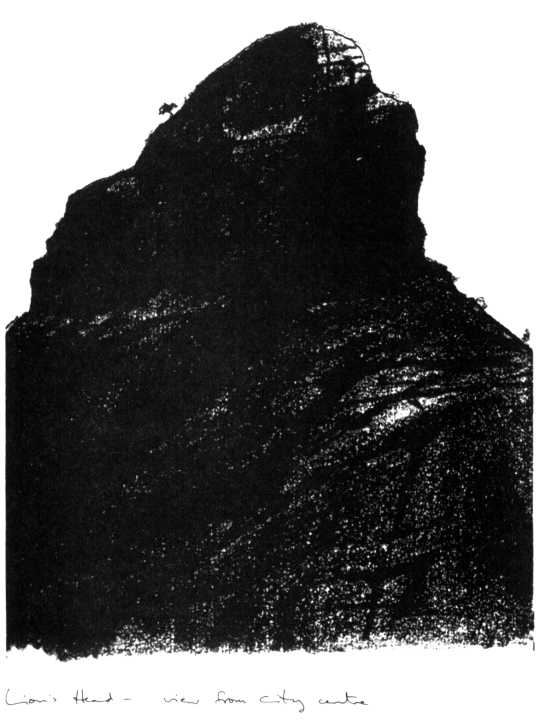

Driving home in a slow circle round Lion's Head. I suddenly realised why

it is so compulsive - the brute force, the thickness. My acting is often described as ratty or rodenty. Richard must be a thicker, heavier animal

if there is to be a tragic dimension.

Ashley has invited me to his firm's Christmas party. He is a champion of

workers' rights and of breaking down colour barriers. Thus the party

tonight is to be held in one of the Coloured townships and he has said it

will be `an education' for me to come along.

Dad is very amused as he sees me to the car. `Well, my boy, you can't

tell me things aren't changing in this country. There was a time when one

wouldn't shake a black by the hand, scared some of the colour might rub

off; now one's doing the foxtrot with them. Anyhow, I'm sure you'll have

a good time once you get used to the smell.' Yvette giggles, daring me.

The dance hall turns out to be a mixture of Spanish restaurant and

Country-and-Western folk club. We walk in past a group of Coloured

youths. One says to another `Lotta white faces here tonight, of pallie.' I

feel quite nervous. Going into this `non-white, non-European' place

breaks every rule that I was taught. Those taboos tacked round our edges

as children, sealing us in.

I am put on a table with Ralph, Ashley's Coloured manager and his

girlfriend Patti, so I can `talk' to them. Bottles of wine and whisky are

plonked down.

At first Ralph is rather guarded on the subject of the referendum and

apartheid, which fuels my interest. A few whiskies later, I steer him

towards these topics again and now it all comes pouring out, but again

not what I expected. Perhaps this is the `education' that Ashley meant.

Ralph talks like a white: how you can't change overnight; how if you did

he'd be blown away in the crossfire between the races; how lazy, stupid

and dishonest the blacks are. Doing a passable impression of Monty I

smile wisely and ask him to think why the blacks are like that. `Look,' he

says, `don't tell me about their backgrounds. I also come from a poor

background, I also been thrown out of places that I go to with my white

friends. But I don't steal. Maybe if you lived here you'd understand.

Things are changing, but slowly. We don't want another Rhodesia. Or

look at the rest of black Africa. Or at your own country - what about that

bomb the other day in Harrods? Look, I'm selfish. I gotta think of me

first, get me sorted out first then I can start worrying about my neighbour.

But please don't get me wrong - I am against apartheid.'

The band strikes up. Ashley crosses the room and asks a large black lady for the first dance. A ripple of applause as they glide on to the floor.

She looks rather embarrassed.

'Look!' Esther almost shouts, snatching my arm. `Look - my son is

dancing with the tea lady! Will you look at my marvellous, wonderful boy.

lie could have chosen anyone for the first dance, instead he chooses to

dance with the lowest paid member of the firm, will you look!'

I say to Ralph, 'I low old are you:

'"Thirty-five.'

'Really? We're the same age. Strange to think that we both grew up in

this city in very different ways. I)id you ever come out to Sea Point','

`Oh vah man, Sea Point is where all the action was, still is.'

'Really', Where

'You know those tall blocks of flats on the beach front, Well, in the

maids' rooms, at the top and at the bottom of those blocks. You know

what they say: "Life's full of spice at the top and at the bottom." '

Later, as we leave, I give Ralph and Patti my address in London. He

says rather furtively, 'Maybe I'd see things differently over there.'

Driving back we pass the black township Langa. Yvette tells how she

worked in a hospital there until the '76 riots. Afterwards, her black

assistant rang her to ask when she was coming back. Yvette said never,

she wasn't allowed to anymore, and they cried together on the phone.

Wake inexplicably depressed about Richard III. Why bother playing the

party Olivier's interpretation is definitive and so famous that all round the

world people can get up and do impersonations of it. At parties in New

York, in bars in Naples, on remote Australian farms and forgotten South

Sea Islands, people get to their feet, hoist one shoulder up, shrivel an arm

and limp across the room declaring, `Now is the winter', or its relevant

linguistic equivalent. Why these thoughts suddenly', It's this fucking

mountain I keep circling!

We've just finished supper when Howard Davies rings. He says their

plans have changed again. I le's no longer doing the Nicky Wright play,

Adrian is. The Peter Barnes play is postponed to the Barbican '85 season.

They're bending the rules slightly for the new season at The Other Place (which was to be exclusively brand new plays) and now in Slot Four is a

revival of Trevor Griffiths's The Party which Howard is directing with

David Edgar. I know the play only by reputation. He wants me to play the

part originally played by Ronald Pickup. The Olivier part is being offered

to McDiarmid, the Frank Finlay part to Mal. I promise to try and find a

copy in Cape Town, but it might be banned either by the South Africans

or Trevor Griffiths himself. Ask him about the rest of the season's casting.

Rees and Branagh are definite, McDiarmid eighty-five per cent but should

be one hundred per cent after The Party offer. `We regard you as sixty-five

per cent,' says Howard.

We watch an old home movie from 1957. It's been transposed on to video

so the quality is appalling, but it's still quite compulsive viewing. If you

had to recreate what memory looks like it could be this. The amateur

cameraman can never settle on anything properly so you have these

restless, tantalising glimpses of people and places and days from long ago.

You ache for close-ups to be held longer but they never are. Sequences

flit by in bleached colours and hazy outlines confirming the popular belief

that the past was one long summer's day. Surprising how exhibitionist I

am at the age of eight: a smiling little boy always in the foreground trying

to hop into shot. At one time I appear in hat and moustache apparently

doing a Charlie Chaplin impersonation. Where is the shy, frightened

recluse Monty and I have spent so long digging out?

`That came later,' says Mum firmly.

Next to her on the sofa Dad sleeps soundly. For as long as I can

remember, as soon as any form of entertainment commences - play, film,

television or even a home movie - he falls instantly into a deep and

contented slumber. Dad lives for his business, lives in a practical commercial world. Perhaps the world of the imagination really has no appeal

whatsoever. When he finds himself in the kind of place where lights will

dim in one area so that a fantasy world can begin to glow in another, he

chooses the darkness.

Now his head jerks up briefly with a sharp snort from the throat,

startling us all except Mum who has learned to ignore these abrupt

comings and goings of her husband. On the screen in our home movies,

a child looms into close-up with large ears and hair carefully brushed for

some ancient birthday party.

`Which one?' he asks, only fractionally awake.

Joel,' Mum says briskly, without altering her concentration.

Juhhh . . .' we hear, as his head falls forward again.

He's always had some difficulty recognising one son from another.

Often when he addresses me, he starts with a little roll-call: `Randall ...

tsk! Joel ... tsk! Antony!'

The highlight of the film is a sequence where Mum and Dad are

dressed as Twenties flappers for a fancy-dress party. Bathed in this film's

eternal sunshine, they dance the Charleston in the back yard of the old

house in Marais Road. He has on an enormous false Groucho moustache

which, with his own big nose and heavy glasses, makes it look like he's

wearing one of those joke-shop faces. We all cry with laughter while he

sleeps on soundly.

Find a copy of The Party. Difficult to read - so was Maydays - but that

same sense of potential theatrical vibrancy once you've understood the

arguments. But I am worried by Shawcross, the part on offer; Iioward

said that he's the one through whose eyes the audience see the action,

but all this means is that he's the straight man to the fun parts, Tagg and

especially Sloman, a wonderful part.

Adrian rings. Puffing deeply on a cigarette between phrases, he reads

me the synopsis of Nicky's play set in Cairo in the Second World War.

It's based on a true story and sounds fascinating, although the character

is too close to Richard III for comfort - trampling over all obstacles to get

promotion. I'm not sure how to react to a synopsis. Adrian makes a little

speech about how they're all desperate to make next year work out for

me, how I must have `two whopping great leads' and how much he wants

to work with me again after King Lear.

I make a return speech on how keen I am to make next year work, that I

am not playing silly buggers and if they could show me the second part in

script form I'd sign on the dotted line tomorrow. But Shawcross isn't it.

Adrian says, `Yes, but that's not meant to be your big second part.

Nicky's play will be that. No, that's just an extra.'

We agree there's nothing further to be said until I've read something.

A first draft might be ready by early January. Wishing one another Merry

Christmas the call ends.

Juices start to flow for Nicky's army play. Harry Andrews from The Hi!!

(and countless childhood improvisations) with ramrod back, lifting his

chin to stretch the neck from a perfectly starched collar; an animal scenting

prey ... promotion.

Another restaurant, mother family meal. An argument rages about maids

and how to treat them. Verne's husband Ronnie is furious because their

maid is using so much gas and electricity in her room. He suspects she

has boyfriends staying over.

Joel says, `Well if you want to keep a maid you'll have to put up with

her human needs.'

`Not necessarily,' says Ronnie crossly, `not given her I Q'

No one will come clean over how much they actually pay these maids,

least of all Mum about Katie. Joel says that if Katie earned what she

deserved after all these years of service she'd be richer than all of us put

together.

I finally get trapped into a furious row about apartheid, the one that

Yvette has been spoiling for ever since I arrived. She says that I've no

right to come here and criticise as I'm doing nothing to help the situation

either here or back in England.

I'm somewhat floored by this. She's absolutely right; here I am having

a wonderful holiday and, like most liberal white South Africans, making

sure that my conscience doesn't intrude too much on my comforts. This

country is so seductive.

Drive to flermanus on the east coast. We've taken a house there for

Christmas week. Mum says that Sea Point is unbearable during the

festivities: `An influx of blacks and Coloureds camping all over the beaches,

the worst element, drunks and skollies!' She says this deterioration of her

beloved Sea Point has converted her from middle-of-the-road liberal

views to a stauncher, harsher belief in apartheid.

After a couple of hours we stop at a fruit and vegetable shop in the

mountains. Dad gulps down a fruit juice and says, `What a waste of a

good thirst, hey?'

An Afrikaner father and son come into the shop. Both are dressed

typically; khaki shirts, khaki shorts, long khaki socks. When Civil War

starts here these people won't even have to change into uniform.