Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (19 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

A nurse had to be called and he suffered the indignity of being given

first aid with the greatest actor in the world passing the bandages. At last

it was done.

Gambon: `Shall I start again?'

Olivier: `No. I think I've got a fair idea how you're going to do it. You'd

better get along now. We'll let you know.'

Gambon went back to the engineering factory in Islington where he was

working. At four that afternoon he was bent over his lathe, working as

best as he could with a heavily bandaged hand, when he was called to the

phone. It was the Old Vic.

`It's not easy talking on the phone, Tone. One, there's the noise of the

machinery. Two, I have to keep my voice down 'cause I'm cockney at

work and posh with theatre people. But they offer me a job, spear-carrying,

starting immediately. I go back to my work-bench, heart beating in my

chest, pack my tool-case, start to go. The foreman comes up, says, "Oy,

where you off to?" "I've had bad news," I say, "I've got to go." He says,

"Why are you taking your tool box?" I say, "I can't tell you, it's very bad

news, might need it." And I never went back there, Tone. Home on the

bus, heart still thumping away. A whole new world ahead. We tend to

forget what it felt like in the beginning.'

78 H A R L E Y STREET I haven't been back here since my accident. The

entrance hall with marble staircase. The old woman in a white coat sitting

at the reception desk, who looks up and asks, `Mister -?' The grand

waiting-room, freezing cold. One or two Arabs asleep, dreaming of warmer

places. False books on the shelves. The same old copies of Country Life,

Sotheby's Previews, South African Panorama.

Completely different atmosphere in the Remedial Dance Clinic itself.

Cups of coffee (sometimes champagne) and gossip from the dance world.

The physios are attractive blonde girls in jeans or track suits, the patients

are proud and beautiful dancers - their injuries seem to make them even

haughtier.

Charlotte diagnoses a sprained neck ligament. She explains: `You know

when you eat oxtail stew, well those little horns that stick out the side ...

I warn her that if she carries on I will pass out and I'm feeling inadequate

enough surrounded by these beautiful people. I have a good old moan

about being injured again. Charlotte suggests I should take it in my stride

like dancers or sportsmen. They accept injury and repair as part of their

jobs. Actors only think to train their voices properly.

`But what's the point of all these months at the gym,' I winge, `if I'm

still getting injured?'

`If you hadn't been going to the gym, the injuries would be more

frequent and far worse. This is the first since the tendon. Given that your

performances are so physical, that's not bad going.'

She attaches suction cups from the interferential machine and sets the

various currents in motion ('This will be a gentle throbbing, this pins and

needles, this like champagne bubbles ...'). I lie there being gently

electrocuted, jerking and jumping, while she expounds her latest Richard

III theory - polio. She does a very impressive impersonation on crutches.

Her calves and feet soft and floppy, each step achieved by throwing the

leg forward from the hip. It looks like Douglas Bader and could be misread

as false legs. But an advantage is that the movement is quite variable and

would avoid specific repetitive strain. A problem would be creating an

illusion of the muscle wastage which, she says, characterises the disease.

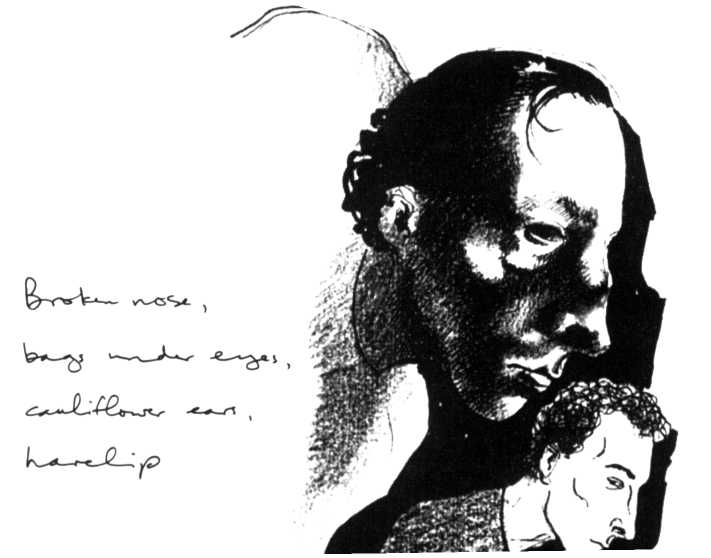

Bill A. says he's been talking to Bill D. and they're both worried about

my drawings for Richard's head. `The trouble is there's no relation to

your own features. It's just another whole head plonked on yours.' Suggests

I think about a boar's head, perhaps with a beard high on the cheekbones

and a spiky wig. I seem to remember that Norman Rodway's image was

boar-like in Terry's 1970 production.

I think what's happened is that both Bills have taken the Hermanus

head too literally.

I try sketching another head alongside a self-portrait, giving it the

minimum of prosthesis, and using my own hair, sleeked back. This is

feasible.

Dickie back for good from filming Passage to India. Lovely stories about

Lean, Ashcroft, Guinness. I try out some Richard ideas on him. The

usual reaction: `Would he be able to go into battle on crutches?' I trust

Dickie's opinion so much this unnerves me. Am I trying to be too clever?

Two Tartuffe's. Overhear that in Henry V Harold Innocent is playing

Burgundy on two sticks. Henry using religious music and featuring a man

on sticks, Merchant having a religious setting, organ music and featuring

two hunchbacks ... all this plunges me into a terrible gloom.

Hurry home to watch Lon Chaney's Hunchback of Notre Dame, hoping

there might be something to steal. But it's appalling. Why is it that silent

comedies have survived so well when silent drama has aged so pitifully?

Our sense of humour more constant than our sense of tragedy?

Increasingly difficult to playMoliere in the theatre because we're rehearsing

the television version during the day. Tonight I found myself reaching for

props that weren't there and heading for a doorway that didn't exist. But

the audience was our best yet, effortlessly able to switch from the comedy

to the tragic melodrama, the laughter huge (like Tartuffe at times), the

silences crystal clear. At the end cheers, and we were called back for an

extra bow.

Moliere has always been the runt in my litter - people unsure about

the play, my performance not really commented on - and hence my

favourite.

Nice to have him cheered tonight.

A C T o N H I L T o N Mild grey weather. The Irish doorman says, `Isn't it a

lovely soft day?' and Mal says, `You can just taste spring on the air.'

Shows falling like flies because of the strike. Terra Nava cancelled last

week, Titus Andronicus this. The pattern is becoming familiar. Each cast

gets increasingly depressed as their studio dates approach; they are

discovered spending more and more time in the canteen, muttering'Nuff

to make you vote Tory.' Then comes the day when they're finally cancelled

- at 11.30 in the morning they head off for the pub to get very pissed,

drowning the memory of all the wasted work.

With our own studio-dates ten days away, we're feeling rather apprehensive now.

Exhaustion of the last few weeks catching up with me. And it could

all be for nothing, this frantic commuting along Westway, rehearsing,

performing, squeezing in visits to the gym.

KOTO JAPANESE RESTAURANT My dinner with Monty. We put

Richard on the psychiatrist's couch and analyse him in depth.

I say, `Tell me how you'd begin if he came to you as a patient.'

`Oi vey! All right, I suppose I would have to start with that mother.' He

points out that there isn't a single moment in the play when the Duchess

of York talks of Richard without contempt and hatred. She shows no

maternal instincts whatever.

`What is it like to be hated by your mother?'

`Very similar to being loved too much. In both cases the mother prevents

the child from developing an accurate sense of self. She distorts his view

of himself.'

When Richard is in turmoil at the end of the play, in the speech after

the ghosts, he keeps asking `Who am I?' Monty explains that, as Richard

hasn't received love as a child, he won't be able to show any himself;

hence his contempt for human life. `What would it feel like to be a

mass-murderer?' I ask.

`They feel very little. Each murder is an attempt to feel, if you like, an

attempt to release anger, an attempt at catharsis, and each time it is

unrelieved. It's like promiscuous sex, sex without love, without feeling.

Each climax is less and less fulfilling so the appetite grows until it's

insatiable.' Monty says that, reading the play again, there is less pain and

anger in the character than he had originally thought.

I ask, `Is that because Shakespeare has given him too pronounced a

sense of humour? Does that make him ghoulish, inhuman?'

`On the contrary. It makes him very human. He can make us laugh, yet

commits terrible crimes. We don't like that. We want killers to be monstrous, inexplicable, inhuman. But how you go about making an audience

cry for him as well as rejoicing in his humour, that I don't know.'

`I don't either. But I think it's something to do with disturbing them.

By not making his humour too comfortable.'

`Good. I like the sound of that.'

Interesting to compare Monty's view of Richard with that of Stopford A.

Brooke in his collection of essays, On Ten Plays of Shakespeare, published

in 1 goy. He describes very precisely the worst way (in my opinion) one

could play Richard's humour: `a chuckling pleasure in his cunning'.

Yet, strangely enough, he and Monty end up with a similar conclusion.

Brooke: `He who has no love has no true sense of right and wrong, and

the absence of conscience in Richard is rooted to absence of love in him.

The source of all his crime is the unmodified presence of self-alone.'

An absence of love. Caused by a hating mother. This is what I will base

my performance on. But I will have to be quite secretive about it, because

it sounds so corny - his mother didn't love him.

Unusual encounter. A stranger wrote, asking to meet. He's an actor

playing the little tomboy Cathy, the part I played, in Cloud Nine. I assume

he will want to discuss the original joint Stock workshop we did before

Caryl Churchill wrote the play, and agree to meet him between shows

today.

It quickly becomes apparent he has something else on his mind. He

just needs to talk to someone and for some reason has chosen me. He

tells me that he is a transsexual (I have to confess to him I'm not sure

what that is; he explains it's wanting actually to change sex) and is finding

the experience of doing the play traumatic. He's a man who wants to be

a woman playing a little girl who wants to be a little boy. The current

situation is only part of the problem. A change of sex is of course feasible,

but would probably entail having to change professions as well. I'm very

struck by his manner. Something beyond despair. He smiles calmly as he

describes the hopelessness of the situation, his gaze is very trusting, open.

Monty was quite wrong: I haven't learnt any of his skills. I feel unable

to make any useful suggestions, except therapy which he's already done

- apparently the therapist was more embarrassed than him and had to

look away for much of the time.

I was moved by the experience, inspired by his courage and grateful to

have met him. If the Shadey film ever gets made and I play the part (which

is a transsexual), this meeting will prove invaluable. As I write this it

sounds vaguely exploitative, but I really don't believe it is. His openness

was a revelation to me.

I'm reading one of the books which Bill Dudley suggested, The Daughter

of Time by Josephine Tey. Although written as fiction it has become the

bible of the Richard III Society (which is pledged to restoring his reputation

in history). It would appear that the real Richard was a good king, a gentle

soul, not at all deformed, and didn't kill the princes in the Tower.

Richmond (later Henry VII) might have done it.

Shakespeare's source was Holinshed whose source was Thomas More's

History of King Richard the Third. But More was only five when Richard

succeeded to the throne and and eight when he was killed at Bosworth.

His source was Morton, Bishop of Ely (he appears as a character in the

play) who in real life hated Richard. Also, More was writing for the Tudors

who wanted their claim to the throne made kosher, Richmond being the

first Tudor.

An interesting read but useless for my purposes. Except that in the

book a doctor studying the famous portrait of Richard diagnoses polio.

Last Maydays. I arrive at the stage door to find our author David Edgar

and his wife there. David is so tall his head brushes most ceilings. He is

chain-smoking as usual and wears a long grey scarf which itself looks like

a giant curl of smoke from floor to ceiling. A joy to fall into the banter

again.

David says, `Ah, Sher. Why aren't you preparing for the performance?

Doing aerobics or mirror-exercises with Alison Steadman or something.

Shouldn't you be thinking your way into character?'

`I find with your writing it is advisable to leave that to the last possible

moment.'

`Have you met my wife, my little wife? Darling, have you met this actor,

this little actor? I am surrounded by all these little people. Oh, may I use

your dressing-room? Make some adjustments to my person - not before

time some would say.'

The show is efficient, workmanlike. Faintly disappointing like all last

nights. We want it to be a definitive performance of the play, the same

thing that we strive for on first nights. But no performance is ever definitive

- the phenomenon doesn't exist.