Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (23 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

Another says, `Science doesn't really know. There may be genetic and

environmental influences intermingling ... we don't really know for sure.

He may simply be evil.'

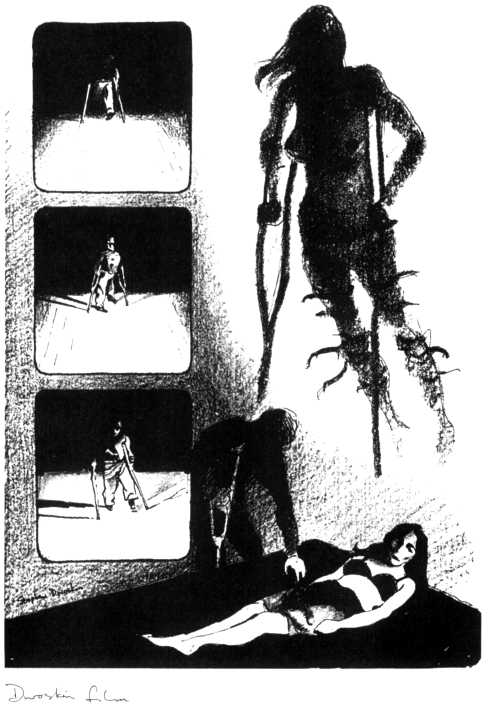

Outside In, Stephen Dwoskin's autobiographical film. Very useful for

Richard. Dwoskin has severe polio in both legs and has to wear complete

calipers, so the legs can't bend at all. He walks with crutches and even

then has enormous difficulty throwing each leg forward. I must use this

- the hip throw. Sexual area. Thrusting. In pain and pleasure.

Dwoskin records his fantasies: beautiful women cleaning his room,

dancing at a party, or stripping at the top of a difficult flight of stairs -

out of reach. A naked woman puts on his calipers and tries out his

crutches.

The tone is light and frivolous - Dwoskin frequently falls over, like a

cartoon man - but it doesn't take much to twist these images into

something more perverse, more Richardian.

Extraordinary sequence with a semi-naked woman lying on a black bed.

She's bathed in a cool white light, her skin like porcelain against the black

of her hair, bra, knickers. He comes alongside her, a dark silhouette,

carefully props himself up on his crutches and stretches out a hand - it

turns from black to white as it enters the light - to touch her. Again and

again without ever making contact. The cripple reaching for a beautiful

whole body.

Another sequence of him limping slowly out of the darkness into a

square of light.

A way of starting the play? The stage in darkness except for a pool of

light. Empty. You hear `Now is the winter' coming from the darkness,

then he starts to limp into the light ...

THE PIT, BARBICAN Volpone. A joy. Richard Griffiths and Miles

Anderson are an inspired double act. A lot to learn from Anderson's

portrayal of evil. He sits back in Mosca's immorality. It's as natural as

breathing. And he's not afraid to shut off the charm and frighten the

audience. But then the face is magnificent, it can change from beauty to

ugliness. John Dicks (Corvino) understands the style so well; I will long

remember the moment someone makes the sign of the cross in front of

him and he frantically tries to claw it out of the air. Bill's production is

brilliant but ... he plays it uncut. Four hours! Who wants to sit in a theatre for four hours? It almost alienates this devoted fan. Particularly

since I know he will try it on with Richard and I will have to fight him to

the death.

Last night I dreamed I was running. All the training, all the exercise had

finally paid off. I was running without panting, without hurting, without

fear of injury. My legs were stretching into long powerful strides. The

lawns were passing beneath me like carpets unrolling. A familiar distance

effortlessly covered.

I woke with a terrific feeling of hope.

Dickie and I go into the West End to see Scarface, the new Al Pacino film.

The cinema is next to St James's Square where the Libyan Embassy siege

continues. We round the corner into Waterloo Place and there's that huge

sheet of blue tarpaulin which has been on the TV news all week. It looks

like an avant-garde theatre curtain, and indeed a crowd of holidaymakers

stand across the street behind barriers, waiting for the show to start. The

mood is festive, hot dogs and ice cream, buskers with performing budgies

and dogs.

Suddenly a group of high-ranking police officers arrive, jumping dramatically out of their cars before they've stopped. They hurry across the

road clutching briefcases and raincoats, and disappear through the blue

curtain. The crowd stirs. Will the show start now that the leading actors

have arrived?

We go into the Plaza and watch a relentless, three-hour succession of

slayings, maimings and coke-sniffings. Emerge grumpily on to the street

at the end, Dickie remarking that it would have been more fun watching

the blue curtain.

Growing excitement now. Tomorrow I move to Chipping Campden.

Dashing around all day, settling bills, last minute shopping, writing letters.

The day is hot like summer.

Try out bits of Richard now and then - a line, a hip thrust - keeping

him near.

RIVERSIDE STUDIOS With Dickie to Poppie Nongena. It's not awfully

good. Like most political theatre it's over-intense and faintly embarrassing.

And yet I sit in a state of tearfulness all evening, partly because of the show's anti-apartheid sentiments, but mostly because I identifywith these

South African actors here in London. It must be tremendously exciting

for them. At the end, the big black Mama leads them in a circle round

the acting area and the audience rise to their feet and cheer.

The most remarkable feature of the show is the singing. They have no

instruments to give them the note. They just stop speaking, put back their

heads and open their mouths. A sound comes up out of the earth, strokes

your spine and goes straight to heaven. The audience holds its breath.

Back home for the late-night film, a favourite, Everything You Always

Wanted To KnowAhout Sex But WereAfraid To Ask. In the Haunted House

sequence Woody Allen whispers to the hunchback, `Posture, posture!'

And so farewells. Dickie has bought a bottle of champagne. We raise

glasses.

`To Richard the Third.'

Wednesday 25 April

ROYAL SHAKESPEARE THEATRE First day of rehearsals. Solus call.

After waiting almost six months for today I manage to arrive late, having

misjudged the drive from Chipping Campden. Charge into the Conference

Hall, hurling apologies down to the other end of the room where a little

group sit waiting: Bill A., Alison Sutcliffe who is to be the assistant

director, and Charles Evans the deputy stage-manager.

I'm delighted to see that Charles is on the show; he did Tartuffe and

Maydays. Charles has the looks of a disgraced cherub, blond curls over

red shiny cheeks which seem permanently in a state of excitement. He

greets me by sticking his tongue out like a gargoyle and flattening it on

his chin.

I say, `Oh God, Charles! You're not doing Richard are you?'

He laughs, a cross between a squawk and a shriek. Exceptionally loud,

it is achieved by opening the throat very wide and sucking the breath

inwards with alarming force.

Bill has been on holiday in Spain and looks brown and well fed. To my

relief he explains that we won't be able to do a company read-through till

next week because Romeo is still to open, and Merchant yet to have its

understudy run; they get priority. So we'll work on bits and pieces till

then.

The Conference Hall has large Gothic doors opening out on to gardens,

and the river - you can even see The Duck. Now Charles closes these,

shutting out the daylight. Home for the next seven weeks.

Bill says, `Right - cuts.'

`Ah,' say I, `a pleasant surprise. I was expecting a fight.'

`Well, I've done some. Not a lot. Not as many as you'll want. But some.'

Before I can say anything he launches into an attack on `lazy cutting, careless butchery'. He says the play is not just a comic melodrama; it

might be the work of a young writer but it has considerable maturity; we

mustn't keep the action going at the expense of the texture and careful

structure of the play. He quotes the example of the Queen Elizabeth scene

which is often cut in its entirety, but is a marvellous replay of the Lady

Anne scene.

`Agreed,' I say, `we mustn't lose it. But it is too long.'

`We'll discuss that when Frances Tomelty is here. I'll just give your

cuts for now, all right?'

`Fine. We certainly mustn't fight on the first day. And not in front of

Charles.'

Charles shrieks, causing papers to fly off the table.

Bill says he'd like to use the New Penguin edition to rehearse with, and

the Arden for notes - these are much better and wittier, but so profuse

there are only about two lines of the play itself per page. Alison will crosscheck both versions and when there are discrepancies we'll choose whichever is more useful for our purposes.

The moment has come to start reading.

Nervously trying to delay, I suggest that we might think about the first

two lines of the play as a potential cut, and thus avoid the most frightening

part of playing Richard III. `Instead, it could begin, "And all the clouds

that lour'd upon our House . . ." no?'

`Just read it,' says Bill grinning.

` "Now is the winter of our discontent ..."

I read badly, rather monotonously or else I over-stress. Mercifully Bill

stops me after about ten lines and starts to pick at words and discuss

meanings.

We have begun.

Bill D. shows me the designs for Richard's three costumes.

The drawing of 'Richard/Basic' is magnificent - a cross between a

pirate and a slug, all in slimy black, wearing an ear-ring, hair spiked

punkishly (modelled on Ian Dury who has polio), the crutches twisted and

gnarled. The nightmare creature is there.

In the second drawing (after `a score or two of tailors to study fashions

to adorn my body') he has Richard in bottle-green, toad-like, and with a

heavily brocaded, multi-layered hat like the ornate heads of some reptiles.

Somehow the green seems wrong. Black, although traditional, is so

powerful. He agrees to change it and stick to black throughout.

The final drawing in black armour is another strong image - a fighting

machine hurtling through battle.

Afternoon session with Mal, looking at the Richard/Buckingham relationship. Much easier reading, now there are two of us. Bill wants there to

be a tension between them throughout, for their rapport to be dangerous

and competitive.

Interesting discovery: one assumes Richard to have an instinctive respect

for Buckingham, but early on he describes him as a `simple gull'. Buckingham hasn't got a genuinely criminal mind, however ambitious and

ruthless he might be. He is astounded when Richard gives him the chop

because he hasn't seen the inevitability of it: everyone surrounding Richard

has eventually to be disposed of, on the principle that anyone Richard can

trust must be untrustworthy.

Food for thought here - the loneliness of dictatorship.

A gym has opened in Stratford just in time for me. I enrol immediately.

It's at the Grosvenor Hotel and is called Grosvenor Bodily Health (the

initials are thus GBH).

Driving home, I fantasise the Richard III reviews. From the good ('The

Best since Burbage') to the bad ('Haven't scoffed so much since O'Toole's

Macbeth. After Richard on crutches can we look forward to Hamlet on a

stick and Lear's iron-lung?').

Dinner with Jim at Lambs, Moreton-in-Marsh, an old haunt from

History Man days, when I lived in Stretton-on-Fosse. The management

have changed and the new man is a scoliotic. Interesting that he wears a

thin shirt and yet you don't notice his back at first. Then, when you do,

you wonder how you could have missed it. Must be a trick in the way he's

learned to hold himself and move.

I am eager to talk to him about it, but am dissuaded by Jim saying that,

if I do, he'll walk out of the restaurant. However, after the meal the man

offers us a brandy on the house and asks where we work, and then

inevitably, `What plays are you doing?'

`Richard the Third,' I answer, watching closely for his reaction; but

there is not a flicker of recognition. `And Jim is doing The Merchant of

Venice.'

He asks, `Is The Merchant of Venice lighter than Richard the Third?'

I think for a moment. `Yes, I suppose it is' (said the Jew to the

Crookback).

Wake early and lie thinking about this business of whether Richard has

to be sexy. The other day Adrian was talking about the Rustavelli production and mentioned how sexy Chkhivadze was. `But then Richard's

got to be sexy hasn't he? For the Lady Anne scene.'

And yesterday Eileen at the stage door whispered to me, `We've heard

you're going to play him on crutches. You're not, are you? He's got to be

sexy. You can't be sexy on crutches.'

And then there was Bev saying, `Richard the Third is the sexiest of

them all.'

Why this obsession with him being sexy? How many severely deformed

people are regarded as sex symbols?

Leafing through the Arden Introduction, I find that the ever-surprising

editor Antony Hammond has included an anecdote from the original

production concerning stage door groupies, which would seem to indicate

that Burbage didn't stint on the sexuality either. It's from John Man-

ningham's diary and also happens to be one of the earliest anecdotes

about Shakespeare himself.

`Upon a time when Burbage played Richard III there was a citizen grew

so far in liking him, that before she went from the play she appointed him

to come that night unto her by the name of Richard III. Shakespeare,

overhearing their conclusion, went before, was entertained and at his

game ere Burbage came. The message being brought that Richard III was

at the door, Shakespeare caused return to be made that William the

Conqueror was before Richard III.'