You Must Change Your Life (21 page)

Read You Must Change Your Life Online

Authors: Rachel Corbett

But the master's liberation was beginning to usher in his disciple's enslavement, or so Rilke described his workload that winter. It had taken Rodin two years to negotiate the bureaucracy and raise funds to cast

The Thinker

in bronze, all of which heaped more paperwork onto his secretary. Rilke found himself struggling to keep up with the boxes of unanswered letters, which now filled two rooms of the house. It took Rilke twice as long to write in French than in German and he refused to settle for less than perfect grammar. Between Rodin's correspondence and his own, Rilke found himself writing hundreds of letters each day.

The job dragged on well past the agreed-upon two hours, and was cutting sharply into his personal writing time. Sometimes he felt the “mass of untransformed material” swelling so large inside him that he fantasized about hopping on the first train out of town and heading to the Mediterranean. The book he had finished there,

The Book of Hours

, had just come out in November and was already attracting far more acclaim than anyone had expected.

Supposedly Rilke never read reviews because doing so felt about as enjoyable as listening to another man admire the woman one loves, he once said. But critics widely praised the

Book of Hours'

ambition in grappling with “the most elevated theme a lyric can attain: the

theme of the Soul's search for God,” as the German patron Karl von der Heydt wrote in an early review. Each of the five hundred copies in the print run would sell within two years, and a second run would be issued at more than twice the original size.

While Rilke was contending with the unprecedented attention, he also needed to update an earlier collection, the

Book of Pictures

, for its second edition. “But I need âonly time,' and where is it?' ” he wondered to Andreas-Salomé. When several German universities invited him to lecture that winter, it seemed like a legitimate occasion to request a little time off, especially since the subject of the tour would be Rodin.

With some reluctance, Rodin granted Rilke the leave, and the poet set off for Germany in February. He was received like royalty at his first stop, near Düsseldorf. But almost as soon as he arrived, news came that his father had fallen ill and might not recover. Rilke made no sudden move toward Prague, instead delivering an electrifying lecture before continuing on to Berlin. He was eager to see both Andreas-Salomé and Westhoff there and to introduce them to each other for the first time. The meeting between the women apparently went beautifully, and afterward, Rilke thanked Andreas-Salomé for treating his wife so warmly.

While Rilke was mingling with aristocracy, his father lay dying in Prague. After two weeks, Rilke received word that Josef had died and there was no one else to tend to his remains. When Rodin heard the news, he rushed the poet a telegram offering his condolences and money, if he needed it. The poet at last made his way to Prague, where he would face his father's body, pale and propped up on pillows, and arrange for his burial. He did not invite his mother to join him at the grave site.

At the end of his life, Josef Rilke had come to accept, in a sorrowful way, his son's profession. But the poet maintained the belief that his father was fundamentally “incapable of love,” and that perhaps Rilke had inherited this deficiency from him. Rilke's delayed response to his father's death probably had less to do with a shortage of love, however,

than it did with a desire to avoid the unhappy childhood memories of Prague. He could not bear to stay there for more than a few days before boarding the train back to Paris.

When he arrived back at the master's house in Meudon, he walked into another depressing scene. Rodin was buried under blankets in his big mahogany bed, suffering from a terrible fever. The old man rarely got sick, but when he did it completely hobbled him. He was also grieving his own loss, that of his dear friend Carrière, who had died of throat cancer that month. Carrière had been not only one of Rodin's earliest artistic advocates, but also a president of the committee to mount

The Thinker

at the Panthéon.

But now the inauguration had been abruptly disrupted, just weeks before it was scheduled to take place. Almost as soon as Rilke had left in February, hostility toward the

The Thinker

grew so intense that it threatened to derail the project altogether. Critics who opposed the plan said that a statue whose pose “suggests a scatalogical idea,” as the novelist Joséphin Péladan described

The Thinker

, did not deserve the prestigious Panthéon placement. Max Nordau, a physician and disciple of Dr. Charcot's who wrote a book on degenerate art, ridiculed the figure, saying its “bestial countenance, with its bloated, contracted forehead, gazes as threateningly as midnight.”

A vandal had even scaled the Panthéon's fence and taken a hatchet to a plaster placeholder of the statue. “I avenge myselfâI come to avenge myself!” the police heard the man yell. When they hauled him off it became clear that he was mentally ill and believed that

The Thinker

's fist-to-mouth pose was mocking the way the poor man ate his cabbages. Even though the attack did not end up being personal, Rodin was shaken by the violent incident.

The prospect of another public scandal drove Rodin nearly to the edge of his sanity. He became so paranoid in those days that once, when a package came in the mail from an unknown sender, he insisted it contained a bomb and buried it in the yard. Some time later a friend wrote back wondering whether Rodin had enjoyed the jar of Greek honey he had sent.

Rilke had to set aside his own concerns now to come to Rodin's aid. He did not dare abandon his besieged master at this vulnerable hour, believing that Rodin was in “need of my support, insignificant as it is, more than ever.” Rodin, meanwhile, was oblivious to Rilke's rising stature abroad and the growing demand for his work.

Rilke managed to preserve this precarious balance for a while, but it could not withstand the disruption that came in April. That month, the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw hired Rodin to sculpt his bust. Then forty-nine years old, the writer was eager to have his portrait done before he “had left the prime of life too far behind.” Shaw's renown as a drama critic for the

Saturday Review

was being increasingly surpassed by his own theater productions, satirical morality plays that now routinely debuted at London's Royal Court Theatre, including, most recently, his comedic drama

Major Barbara

. A socialist and a vegetarian, Shaw infused his plays with passionate political messages that were tempered by his lively wit.

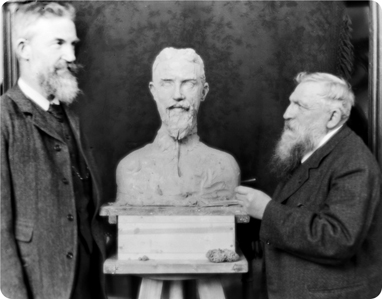

Rodin, who possessed neither drive and spoke no English, did not know Shaw's work at all when they met. Since the sculptor was still recovering from the flu at the time, he asked the writer to come to him in Meudon for the twelve sittings, rather than to his more conveniently located studio in Paris. Shaw agreed and paid twenty thousand francs for the sculpture in bronze. One would have to be a “stupendous nincompoop” to have a bust done by any other artist, he said.

But Shaw was wholly unprepared for the grueling weeks ahead. In their first sessions, Rodin took a big metal compass to Shaw's head to measure it from the top of his red crown to the tip of his forked beard. Then he molded the face from sixteen different profiles. Once Shaw was sure he had been examined from every possible angle, Rodin told him to lie down on the sofa so he could capture the views from behind the forehead and below the jaw. Finally, once Rodin approved of the basic form, he began scooping out the features.

Mesmerized by Rodin's meticulous process, the playwright later wrote about it in a remarkable essay from 1912:

In the first fifteen minutes, in merely giving a suggestion of human shape to the lump of clay, he produced so spirited a thumbnail bust of me that I wanted to take it away and relieve him of further labor . . . After that first fifteen minutes it sobered down into a careful representation of my features in their exact living dimensions. Then this representation mysteriously went back to the cradle of Christian art, at which point I again wanted to say: âFor Heaven's sake, stop and give me that: it is a Byzantine masterpiece.' Then it began to look as if Bernini had meddled with it. Then, to my horror, it smoothed out into a plausible, rather elegant piece of 18th-century work . . . Then another century passed in a single night; and the bust became a Rodin bust, and was the living head of which I carried the model on my shoulders. It was a process for the embryologist to study, not the aesthete. Rodin's hand worked, not as a sculptor's hand works, but as the Life Force works.

Perhaps it was during those long hours sitting for Rodin that Shaw first developed his sympathies for artists' models. A few years later he would rewrite the Greek myth of Pygmalion, an artist who fell in love with his own sculpture, but from the point of view of the model. Shaw named this figure Eliza Doolittle.

Despite Shaw's admiration for Rodin's work, the two men were opposing personalities from the start. Shaw was a playful raconteur and Rodin was virtually humorless, especially in those days. During the countless hours they spent together, Shaw recalled seeing the sculptor laugh only onceâa light chuckle when he watched Shaw feed half his dessert to Rodin's dog, Kap.

But because Shaw refused to take anything seriously, Rodin's severity became all the more amusing to him. Seated in a child's chair, Shaw fought back laughter while Rodin spat water onto the clay head without noticing that it also splattered the man posed behind it. He watched with “indescribable delight” as Rodin whacked creases away

with his spatula and, once, sliced through the neck with a wire and tossed the decapitated head casually aside.

Shaw's attempts to crack jokes through his broken French did nothing to ease matters. When someone once asked Rodin what the two men talked about during their sessions, he replied, “M. Shaw does not speak French well, but he expresses himself with such violence that he makes an impression.” Rodin, whose English was even worse than Shaw's French, confused everyone when he pronounced the name of his sitter, “Bernarre Chuv.”

Rilke was as ignorant of English literature as Rodin, but he found Shaw to be a far more entertaining guest. He thought the man was every bit as clever as Oscar Wilde, but with none of the pretension. As the originally planned sittings stretched out into three weeks, he also became impressed by him as a model. Rather than merely standing still, Shaw stood with purpose and determination, like a column that supports more than its own weight. Soon Shaw was spending many of those afternoons chatting with Rilke instead of Rodin.

Rilke began to wonder if perhaps Shaw should be the subject of his next work. He wrote a letter to the playwright's publisher, praising the man as an excellent, energetic model. “Rarely has a likeness in the making had so much help from the subject of it as this,” he said. He then asked whether they might send him some of Shaw's books so he could consider writing about them.

At last, Rodin received some news to lighten his mood that spring. A committee of prominent artists, politicians and the president of the Society of Men and Letters, which had previously rejected Rodin's

Balzac

, united in support of installing

The Thinker

at the Panthéon. The committee overpowered Rodin's critics and the statue was officially unveiled on April 21.

Rilke sat with Shaw and his wife during the celebration. They watched the city's arts undersecretary Henri Dujardin-Beaumetz welcome

The Thinker

and Rodin with a lofty speech. After years of misunderstanding, “this truly creative artist, so shaped by humanity and

conviction, is finally able to work peacefully in the shining light of universal admiration,” he said.

Joining the group for the festivities was Shaw's friend Alvin Langdon Coburn, an artist who had come from London to photograph Rodin. Shaw, who was an amateur photographer himself, had been carrying around a box camera in Meudon when Rodin noticed it and invited him to take as many pictures as he liked. Shaw shot one photo of Rilke leaning against a stone rail in Meudon, looking heavy-lidded and worn. But when it came to capturing Rodin, Shaw told Coburn that he ought to be the one to do it. “No photograph yet taken has touched him: Steichen was right to give him up and silhouette him. He is by a million chalks the biggest man you ever saw; all your other sitters are only fit to make gelatin to emulsify for his negative.”

Coburn jumped at the opportunity. He took dozens of photographs over the next few days, of Rodin, his art, and one of the sculptor and Shaw together with the bust-in-progress standing between them. Shaw had not overstated his description of Rodin, Coburn thought. “He looked like an ancient patriarch, or prophet.”

On Shaw's last day in Paris, he was preparing a bath when an idea came to him. Once he got out of the tub, he told Coburn to take a photo of him assuming the pose of

The Thinker

âbut nude. The men laughed while Coburn took the shot and then they boarded the next train back to England.

When the photo went on view at the London Salon later that year, critics responded with revulsion and disbelief that Shaw would participate in such a shameful portrayal. He tried to defend himself by saying that busts conveyed only a person's reputation, while full-body portraits showed nothing “except their suits of clothes with their heads sticking out; and what is the use of that?” This photo showed Shaw as he really looked. Or perhaps it was simply a joke that spiraled out of hand.

Shaw was stunned when he laid his eyes on the three completed bustsâin plaster, bronze and “luminous” marble. “He saw me. Nobody else has done that yet,” Shaw said of Rodin. His wife said it looked so

much like her husband that it scared her. On the forehead sat the two locks of hair that parted like red devil horns. The subtlest hint of a smile lurked behind an otherwise expressionless face.