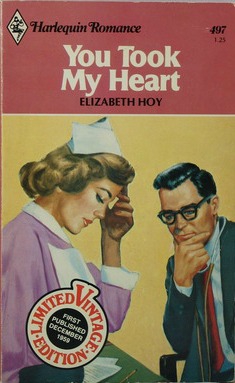

You Took My Heart

Authors: Elizabeth Hoy

YOU TOOK MY HEART

Elizabeth Hoy

He had always been her anchor.

Joan Langden had loved Garth Perros all her young life, and she believed, as she grew older, that he was coming to love her, too.

Why else would Garth suggest that she take her nurses’ training at the London hospital where he himself was a brilliant surgeon?

But she learned that life was not that easy. Garth’s past held a dreadful secret—one that seemed destined to keep them apart.

CHAPTER ONE

Joan was

out of bed that morning before the great hospital bell had ceased its clamor. Other mornings it wouldn’t be like this. Other mornings she would lie lingeringly as most of the nurses did until the last possible moment. But today she couldn’t be quick enough reaching out for the unfamiliar starched pink frock and crisp white linen. A soft pink it was, the color of hedge-roses in June, very becoming indeed to Joan’s fair skin glowing now after her hurried shower. She was glad it wasn’t an ugly uniform at St. Angela’s. Fastening the snowy cap on her brown-gold hair she surveyed herself in the mirror, her pointed face eager, her blue eyes bright and expectant for all that this day might bring.

Feeling a little guilty she dabbed powder on her small nose. Miss Darley didn’t approve of make-up; white-haired, autocratic Miss Darley sitting aloof as a goddess in her office to interview tremulous newcomers.

“I like my nurses to look nice, Miss Langden,” she had said to Joan on her arrival yesterday. “And a face plastered with cosmetics is

not

nice. It is a nurse’s business to be unobtrusive in her appearance.” And Joan had murmured, “Yes, Matron,” respectfully, with a sinking heart. Shiny noses were awful, so were pallid countenances and anaemic lips.

But later Gemma Crosbie, her room-mate, had told her every nurse in the place carried a beauty compact in her uniform pocket. It was all right as long as you didn’t over-do it with the powder and lipstick. Miss Darley would never know. That was the way it was, Gemma said, with hospital rules. There were hundreds of them, but for most of them one could find safe little evasions. Otherwise life wouldn’t be bearable.

When she was dressed Joan stepped out of the french window on to the iron balcony beyond. It was six o’clock on a perfect summer morning; just the right sort of morning for beginning life all over again, Joan thought. It might have been a country sky above her head, so blue and pure it was; and the garden of the square beneath, laid trim and fresh with its tended lawn and borders of flowers, might have been a hundred miles from the centre of London.

On the other side of that oasis of grass and trees lay the main portion of the hospital. Joan saw it now with a thrill of importance ...

her

hospital. For four years its wards would be her home, its background of suffering and healing her teacher. Would she be successful, she wondered? You had to be a “born nurse” they said. Was she? She didn’t know. Only that she had always enjoyed helping Dad with the sick folk of his parish, visiting the mothers with new babies and the old ladies with rheumatism. Often she had made herself quite useful in emergency in the cottage homes of Dipley-on-the-Marshes, and in the end she had nursed her father through his two painful years of illness before he died.

Perhaps it was that more than anything which made her decide that nursing was her vocation ... those empty days after Dad was gone, and there was no more need of her vigilance. She had felt so lost and forlorn. She had wanted passionately to go on caring for somebody, being important to somebody, being needed.

It was Garth Perros who had suggested St. Angela’s. “If you like to try your luck with us I’ll put in a good word for you with Matron and the committee,” he had written.

Joan felt she

would

like to try her luck at St. Angela’s with Garth somewhere in the background.

But just how much Garth counted in her scheme of things she would not let herself think as she hurried down the staircase of the Nurses’ Home that summer morning in her pink frock and new white apron.

There were dozens of pink frocks running across the square now, like crumpled rosy flowers on the grey London pavement, dozens of fresh young voices calling. Miss Darley liked you to be as quiet as a nun on those brief journeys from the home to the hospital, but Miss Darley would be sleeping still in her cloistered apartment behind the office. Only Miss Don, her second-in-command, would be on the alert, her hard black eyes peering from behind her bedroom curtains for over-ebullient probationers. Miss Don, known to disrespectful underlings as “Donald Duck” because of her strident voice, was a tartar.

“If Donald Duck sees us using the gardens as a short cut we’re done,” Gemma Crosbie told Joan as they hurried along.

“But why shouldn’t we cross by the garden? It’s so much nicer this way,” Joan said, sniffing the dewy freshness of morning flowers and wet grass.

“Because we wear out the lawn

—

trample it. At least that’s what

she

says. As though we were a herd of elephants! Grass to old Donald is something to ‘please keep off.’ ”

With a whisk of her starched skirts Gemma jumped over the forbidding little notice.

Then they were running up the wide steps of the hospital entrance and the glass doors swung back to admit them. Joan’s heart fluttered. She was glad of Gemma now. Gemma was probationer in Dale Ward, the women’s surgical, where Joan had been listed to begin her duties. Gemma was a veteran of six

w

eeks’ experience. She was ready to tell Joan all she knew, thrilled to tell. For too long she had been the j

u

nior in Dale. Now there would be someone even greener and newer than herself to take on those everlasting “screens” and help with the sweeping and brass polishing.

As the lift sped upwards Gemma whispered dramatically, “Millet is the God Almighty up here— she’s Sister-in-charge. Scatt is the staff nurse. A bit of a bully, but O.K. if you handle her right. Don’t let her hear you calling her ‘Scatty’ though, and never let her, see when

you’re

afraid. She’ll give you the most hair-raising jobs to do, but if you start in on them without fussing she comes to the rescue and helps you out. If you whine she has no use for you.”

The lift stopped with a jerk. Joan drew in a quick breath. The corridor before them was white and gold with sunlight and full of flowers. On every windowsill and available shelf the massed pitchers stood, bright with late roses and flaming spikes of gladioli. The scent of the roses struggled with those other terrifying odors, creosote and either soap and the tang of carbolic.

Gemma took Joan into the ward-kitchen and introduced her. Nurse Scatt scarcely looked up, which, Joan felt, was rather surly of her. But she was busy listening to the report of a weary-eyed night-nurse. Later on, when she had time, she might more adequately acknowledge the existence of the unimportant newcomer.

“Mrs. Jenkins had a hypo at three a.m. Old Eldon slept well—” the night-nurse was saying.

Gemma and Joan went away to make the ward-beds. It was the first duty of the day. There were twenty beds in “Dale,” ranged closely together against the green distempered walls. It was a large pleasant room lighted by an enormous bay window overlooking the square and its trees., The floor was bare, but brilliantly polished. There was a fireplace at either end and in the centre a white enamel table, upon which stood a bowl of pink glyco-thymol and jars of swabs.

Gemma said, “We’re supposed to give three minutes to each bed, so for heaven’s sake, Langden, look snappy!”

Joan tried hard, but at first her fingers were all thumbs. There were so many things she was supposed to know ... things no one it seemed had time to tell her. There was a special way of turning in the corners of the blankets, and you didn’t tuck in the top sheet, just folded it over in a most peculiar fashion that Joan couldn’t help thinking must be uncomfortable for the occupant of the bed.

The first two beds they flew at were empty because the almost convalescent patients belonging to them were in the bathrooms washing. They had them stripped, turned and remade well within the scheduled minutes. Joan looked a little breathlessly at the remaining eighteen beds. There were helpless folk lying in every bed ahead of them.

Gemma in an undertone tried to tell her how to manipulate the pillows and blankets with the least possible discomfort to the patients. In bed number three was a heavy old lady who groaned constantly. Joan felt awful trying to lift her and turn her while Gemma did lightning things with the coverings. Gemma called the old lady “Granny,” and talked to her in a bright, high, unnatural voice which was meant to be encouraging. But the brighter Gemma was the more the old lady groaned.

“What’s the matter with her?” Joan whispered as they moved away at last from her completely smoothed and speckless couch.

“Dismal old trout! Had an Enterectomy done last week,” said Gemma, who had no idea what an Enterectomy might be. But her glib reply stunned Joan, who felt her abysmal ignorance more deeply than ever before this display of surgical phraseology. Enterectomy, she decided, must be a most painful disease if the old lady’s groans were anything to go by. Why didn’t somebody give her morphia or something? Morphia was a sedative. At least she knew that much.

“Lumbar Nephrectomy done yesterday. Go easy with this one,” Gemma panted at bed number four. Joan’s hands shook with concern as she picked up the cheerful red top blanket and folded it back.

By eight o’clock, breakfast-time, she was feeling a wreck. She had, with Gemma, fixed and washed and fed twenty helpless and mostly seriously ill people. The names of their ailments alone, reeled off by Gemma, made her feel powerless; the fear of hurting them in her ministrations left her shaken. The ritual known as “screens” had brought her sharply to the realization that there was no use being a nurse if you were going to be squeamish.

And after “screens” Gemma had set her to mopping out three large, tiled bathrooms. Already with aching back and roughened hands she felt as though she had done a day’s work; but the day had hardly begun. At this rate she would scarcely survive a week at St. Angela’s, let alone four years. She was ready to weep with discouragement over her porridge-plate. The food stuck in her throat. All around her the pink-clad probationers chattered like so many cheerful magpies.

Gemma at her side introduced her perfunctorily to one or two of the nearest girls. “This is Langden, was Gemma’s invariable formula. “Better be nice to her. She’s a friend of the great Garth Perros! He brought her here.”

“Mr. Perros! Did he really?” They were two of the senior probationers leaning across the table, gazing with avid interest now at the newcomer. “Do you know Garth awfully well?” they asked in chorus.

Joan said yes, she did know him well. He’d lived in her home village as long as she could remember. She was furious with herself for having mentioned Garth to the talkative Gemma, furious with herself for coloring now as she spoke of him.

“He’s a pet,” gushed one of the seniors. “And so divinely good, looking. They say he is the most brilliant honorary we have.”

“What exactly

is

an honorary?” Joan asked out of her ignorance, though her impulse was to drop the subject of Garth as quickly as possible.

“A visiting consultant—either physician or surgeon,” explained the senior. “Usually they are men with West End practices and big refutations. They give their services to the hospital free.”

“Oh!” breathed Joan softly, tackling her scrambled eggs with a suddenly recovered appetite. So Garth at twenty-nine was an “honorary.” An important surgeon with a reputation. She had known only vaguely of his connection with St. Angela’s. She hadn’t been sure just what it was. It warmed her heart to hear the quick commendation of him in this girl’s voice. It made her glow with secret happiness to think that she might see him soon at his work ... might see him this very morning. She had written to him that she would be beginning her duties today. Would he be looking out for her?

He was. He found her in the sunny corridor, her arms full of spiked gladioli. Millet had given her the flowers to “do” because everyone was tired of her bunglings, she supposed. Changing the water in the flower-vases and carrying them into the ward was something she could achieve without help or teaching. Not that they weren’t being terribly patient with her; they were. But they were so busy, so overworked at this hour of the morning, and already Scatty had wasted a valuable quarter of an hour showing her how to read thermometers and take pulse-rates. The sense of her inevitable slowness and amateurishness in this hive of industry weighed on Joan more heavily with each moment that passed.

But now suddenly she forgot all about that. Garth was coming towards her down the long corridor, smiling his

nice twinkly smile. He looked tall and impressive in his white coat, the sun glinting on his dark head.

He said, “Hello, Joanna! It’s good to see you, old thing.” He took her hand and held it tightly. She was pink as her frock smiling up at him.

Joanna. That was Garth’s special name for her. He’d called her Joanna to tease her when she was seven and he was a mischievous grammar-school boy, and the name had stuck. She liked it now because no one but Garth had ever thought of calling her Joanna. It was the secret insignia of their friendship.

She said, “Garth, you make me homesick for Dipley—just the very sight o

f

you.”

“I know, my dear,” he answered, the twinkle leaving his grey eyes. “It must have been hard for you getting away yesterday. But you’ll soon get over that here with all this bustle around you.”

He meant, she knew, that she would get o

v

er Dad’s death now and sayi

n

g good-bye to the whitewashed rectory with its mellow garden; that the old life would fade away from her painlessly, rapidly, as this new life took its place. She smiled up at him bravely.

“Bustle is the right word,” she agreed with a chuckle. “I’ve never dreamed mere human beings could accomplish as much in one single morning as St. Angela’s nurses do. We make beds in three minutes and wash twenty people in half an hour.”

Garth said, “That’s nothing. You wait till you go on duty in the Out Patient’s block. We see a hundred folk a day down there easily, to say nothing of emergency calls.”

Joan felt shuddery. “I know. Going out in the ambulance to street accidents! Do you think I’ll ever be brave enough to face it?”

“Of course you will,” Garth told her heartily, and she looked up to see Sister Millet’s disapproving countenance in the ward-kitchen door.