Zelda (28 page)

Authors: Nancy Milford

Two years ago in America I noticed that when we stopped all drinking for three weeks or so, which happened many times, I immediately had dark circles under my eyes, was listless and disinclined to work. I gave up strong cigarettes and, in a panic that perhaps I was just giving out, I applied for a large insurance policy. The one trouble was low blood-pressure, a matter which they finally condoned, and they issued mc the policy. I found that a moderate amount of wine, a pint at each meal made all the difference in how I felt. When that was available the dark circles disappeared, the coffee didn’t give me excema or beat in my head all night, I looked forward to my dinner instead of staring at it, and life didn’t seem a hopeless grind to support a woman whose tastes were daily diverging from mine. She no longer read or thought, or knew anything or liked anyone except dancers and their cheap satellites. People respected her because I concealed her weaknesses, and because of a certain complete-fearlessness and honesty that she has never lost, but she was becoming more and more an egotist and a bore. Wine was almost a nessessity for me to be able to stand her long monologues about ballet steps, alternating with a glazed eye toward any civilized conversation whatsoever.

Now when that old question comes up again as to which of two people is worth preserving, I, thinking of my ambitions once so nearly-achieved of being part of English literature, of my child, even of Zelda

in the matter of providing for her—must perforce consider myself first. I say that without defiance but simply knowing the limits of what I can do. To stop drinking entirely for six months and see what happens, even to continue the experiment thereafter if successful—only a pig would refuse to do that. Give up strong drink permanently I will. Bind myself to forswear wine forever I cannot. My vision of the world at its brightest is such that life without the use of its amentities is impossible. I have lived hard and ruined the essential innocense in myself that could make it possible, and the fact that I have abused liquor is something to be paid for with suffering and death perhaps but not with renunciation. For me it would be as illogical as permanently giving up sex because I caught a disease (which I hasten to assure you I never have.) I cannot consider one pint of wine at the days end as anything but one of the rights of man.

Does this sound like a long polemic composed of childish stubborness and ingratitude? If it were that it would be so much easier to make promises. What I gave up for Zelda was women and it wasn’t easy in the position my success gave me—what pleasure I got from comradeship she has pretty well ruined … Is there not a certain disingenuousness in her wanting me to give up all alcohol? Would not that justify her conduct completely to herself and prove to her relatives and our friends that it was my drinking that had caused this calamity, and that I thereby admitted it? Wouldn’t she finally get to believe herself that she had consented to “take me back” only if I stopped drinking? I could only be silent. And any human value I might have would disappear if I condemned myself to a life long ascetism to which I am not adapted either by habit, temperament or the circumstances of my metier.

For portions of August and mid-September Scott vacationed in Caux. He finished “One Trip Abroad” and “A Snobbish Story” during those periods of relative peace. But he did nothing with his novel. He had begun to work on a sixth draft in the spring of 1930, but with Zelda’s illness he apparently put it aside and turned to writing short stories for quick cash. At the beginning of “One Trip Abroad” (which Matthew Bruccoli rightly calls “a miniature of

Tender Is the Night”)

Fitzgerald wrote about “the young American couple” Nicole and Nelson Kelly: “Life is progressive, no matter what our intentions, but something was harmed, some precedent of possible non-agreement was set. It was a love match, though, and it could stand a great deal.” The Kellys, who showed signs of being modeled after both the Fitzgeralds and the Murphys, did stand a great deal, until restlessness and their own inner resources began to give way. At the end of

the story Nicole says,” ‘It’s just that we don’t understand what’s the matter…. Why did we lose peace and love and health, one after the other? If we knew, if there was anybody to tell us, I believe we could try. I’d try so hard.’”

During that time Zelda wrote to Scott:

I hope it will be nice at Caux. It sounds as if part of its name had rolled down the mountainside. Perhaps when I’m well I won’t be so afraid of floating off from high places and we can go to-gether.

Except for momentary retrogressions into a crazy defiance and complete lack of proportion I am better. It’s ghastly losing your mind and not being able to see clearly, literally or figuratively—and knowing that you can’t think and that nothing is right, not even your comprehension of concrete things like how old you are or what you look like—

Where are all my things? I used to always have dozens of things and now there doesn’t seem to be any clothes or anything personal in my trunk— I’d

love

the gramophone—

What a disgraceful mess—but if it stops our drinking it is worth it—because then you can finish your novel and write a play and we can live somewhere and have can have a house with a room to paint and write maybe like we had with friends for Scottie and there will be Sundays and Mondays again which are different from each other and there will be Christmas and winter fires and pleasant things to think of when you’re going to sleep—and my life won’t lie up the back-stairs of music-halls and yours won’t keep trailing down the gutters of Paris—if it will only work, and I can keep sane and not a bitter maniac—

Dear Scott:

I wish I could see you: I have forgotten what it’s like to be alive with a functioning intelligence. It was fine to have your post-card with your special reaction to Caux on it. Your letters are just non-commital phrases that you might write to Scottie and they do not help to unravel this infinite psychological mess that I’m floundering about in. I watch what attitude the nurse takes each day and then look up what symptom I have in Doctor Forel’s book. Dear, why has my ignorance on a medical subject which has never appeared to me particularly interesting reduced me to the mental status of a child? I know that my mind is vague and undisciplined and that I only know small smatterings of things, but that has nothing to do with cerebral processes….

I don’t know how we’re going to reverse time, you and me; erase and begin again—but I imagine it will be automatic. I can’t project myself into the past no matter how hard I try. There are lots of days when I think it would have been better to give me a concise explanation and let it go—because I know so much already. One illusion is as good as another.

Write me how you are and what you do and what the world is like at Caux— and Love Zelda

As the summer passed Zelda wavered between a seeming recuperation and yet deeper illness. Once when things seemed very black indeed for her recovery Dr. Forel asked her as part of his therapy to write out a summary of the way she felt about her family and herself. In this document she was able to reveal something of herself to Forel for the first time, with fewer of the restraints and disguises she usually employed. She wrote quickly and in a highly idiosyncratic French. (The following are excerpts from a translation of that record, which in the original runs to about seven pages.) Dr. Forel asked Zelda to describe her parents. She remembered her mother as being extremely indulgent of others’ faults, an artistic woman who wrote, played the piano and sang. Zelda said Mrs. Sayre had a passion for flowers and birds. She saw her mother in terms of a mood photograph: “I can always see her sitting down in the opalescent sunlight of a warm morning, a black servant combing her long grey hair.” But no such images of her father came to mind. She described him exclusively in terms of what he was and did. She said he was a man without fear—intellectual, silent, serious. He was a man of “great integrity.” “I had an enormous respect for my father and some mistrust.” Then he asked her about their marriage.

When I was a child their relationship was not apparent to me. Now I see them as two unhappy people: my mother dominated and oppressed by my father, and often hurt by him, he forced to work for a large family in which he found neither satisfaction nor a spiritual link. Neither of them complained.

When asked about her parents’ influence on her, Zelda insisted that they had had absolutely none.

Her relationship toward her brother and sisters she simply described as “vague.” She was a great many years younger than they and did not have memories of a youth passed together. Her sisters were pretty; she quarreled with them constantly. Her favorite was Rosalind, who “appeared elegant, perfumed, sophisticated.”

The great emotional events of her life were:

My marriage, after which I was in another world, one for which I was not qualified or prepared, because of my inadequate education.

And:

A love affair with a french aviator in St Raphael. I was locked in my villa for one month to prevent me from seeing him. This lasted for

five years. When I knew my husband had another woman in California I was upset because the life over there appeared to me so superficial, but finally I was not hurt because I knew I had done the same thing when I was younger.

Minnie Machen,

“The Wild Lily of the Cumberland”

Zelda Sayre

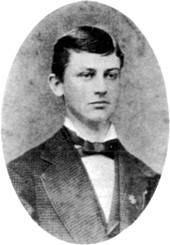

Anthony Dickinson Sayre, age 19

Zelda, age 15