Read 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series) Online

Authors: Gary Provost

100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series) (7 page)

BOOK: 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series)

10.94Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Read aloud what you write and listen to its music. Listen for dissonance. Listen for the beat. Listen for gaps where the music leaps from sound to sound instead of flowing as it should. Listen for sour notes. Is this word a little sharp, is that one a bit flat? Listen for instruments that don’t blend well. Is there an electric guitar shrieking amid the whispers of flutes and violins? Imagine the sound of each word as an object falling onto the eardrum. Does it make a soft landing like the word

ripple,

or does it land hard and dig in like

inexorable

? Does it cut off all sound for an instant, like

brutal,

or does it massage the reader’s ear, like

melodious

?

ripple,

or does it land hard and dig in like

inexorable

? Does it cut off all sound for an instant, like

brutal,

or does it massage the reader’s ear, like

melodious

?

There are no good sounds or bad sounds, just as there are no good notes or bad notes in music. It is the way in which you combine them that can make the writing succeed or fail. It’s the music that matters.

Writing should be conversational. That does not mean that your writing should be an exact duplicate of speech; it should not. Your writing should convey to the reader a sense of conversation. It should furnish the immediacy and the warmth of a personal conversation.

Most real conversations, if committed to paper, would dull the senses. Conversations stumble, they stray, they repeat; they are bloated with meaningless words, and they are often cut short by intrusions. But what they have going for them is human contact, the sound of a human voice. And if you can put that quality into your writing, you will get the reader’s attention.

So mimic spoken language in the variety of its music, in the simplicity of its words, in the directness of its expression. But do not forfeit the enormous advantages of the written word. Writing provides time for contemplation. Use it well.

In conversation the perfect word is not always there. In writing we can try out fifteen different words before we are satisfied.

In conversation we spread our thoughts thin. In writing we can compress.

So strive to make your writing sound like a conversation, but don’t make it an ordinary conversation. Make it a good one.

This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five-word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety. Now listen. I vary the sentence length, and I create music. Music. The writing sings. It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony. I use short sentences. And I use sentences of medium length. And sometimes when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that bums with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals—sounds that say listen to this, it is important.

So write with a combination of short, medium, and long sentences. Create a sound that pleases the reader’s ear. Don’t just write words. Write music.

Most sentences have a subject, a predicate, and an object, and early in life we were taught to present them in that order. The dog ate the bone. Dick and Jane jumped into the river. A man walked down the street. Et cetera.

But identical sentence constructions bore readers. Certainly you should strive for clarity and not arrange your sentences in a way that strangles their logic. But you should also keep the primary elements of the sentence dancing so that they will create their own music.

Below are two paragraphs in which all the sentences are constructed the same way. They all begin with the subject, move on to the predicate, and end with an object if there is one. What conclusion about the writer do you draw after reading them?

The Welcome Wagon Lady twinkled her eyes and teeth at Joanna. She was sixty if she was a day. She had ginger hair, red lips, and a sunshine-yellow dress. She said, “You’re really going to like it here! It’s a nice town with nice people! You couldn’t have made a better choice!” Her brown leather shoulder bag was enormous. It was old and scuffed. She dealt Joanna packets of powdered breakfast drink from it. There was soup mix. There was a toy-size box of non-pollutant detergent. There was a booklet of discount slips that were good at twenty-two local shops. There were two cakes of soap. There was a folder of deodorant pads.Joanna stood in the doorway. Both hands were full. She said, “Enough, enough. Hold. Halt. Thank you.”

The sentences are all simple constructions—grade school concoctions. One of the marks of an inexperienced writer is his or her inability to move beyond these basic sentence constructions. If Ira Levin’s best-selling novel had opened with those sentences, odds are good it would have been a worst-selling novel. But, it didn’t. The actual opening of Ira Levin’s

Stepford Wives

(Random House) follows. As you read it, take note of the variety of sentence constructions.

Stepford Wives

(Random House) follows. As you read it, take note of the variety of sentence constructions.

The Welcome Wagon Lady, sixty if she was a day but working at youth and vivacity (ginger hair, red lips, a sunshine-yellow dress), twinkled her eyes and teeth at Joanna and said, “You’re really going to like it here! It’s a nice town with nice people! You couldn’t have made a better choice!” Her brown leather shoulder bag was enormous, old and scuffed; from it she dealt Joanna packets of powdered breakfast drink and soup mix, a toy-size box of non-pollutant detergent, a booklet of discount slips good at twenty-two local shops, two cakes of soap, a folder of deodorant pads—“Enough, enough,” Joanna said, standing in the doorway with both hands full. “Hold. Halt. Thank you.”

Usually, only a complete sentence expresses a complete thought. A complete sentence has a subject and a predicate. “The cat jumped off the roof” is a complete sentence. “The cat jumped” is also a complete sentence. “The cat,” however, is not a complete sentence. You should try to write complete sentences.

However, if your high school English teachers told you that all incomplete sentences were unacceptable, they were wrong. Good writing often contains incomplete sentences. The incomplete sentence is a useful tool. Used wisely it can invigorate the music of your words. Like a chime. Or the beat of a drum.

Here are two examples. The first is from my story, “The Eight Thou.” The second is from Ping by Gail Levine-Freidus.

“Be damned if I know,” Charlie said. He got the cop laughing, then he patted him on the elbow and said, “Hey, look, you got a couple of cigarettes? I could be in this place for a long time. Years maybe.”This is the way Charlie liked to work them. Shoot the breeze. Crack jokes. Butter them up. Be cute. Then hit them for what you really want. He had charmed his way down from Burlington, Vermont, this way, thumbing and lying like a carnival barker all the way into Boston. His real dream was the West Coast. California. But he’d figured a big city like Boston would be the place to stop first and somehow hustle up a couple of hundred bucks for the cross-country trip. Unfortunately, the Boston P.D. hadn’t been quite as enchanted by his spiel as some of the people who had given him rides. He hadn’t been in town long. Ten days. And this was his third arrest.When I first arrived, I saw nothing. In time I discovered light. White light. And weightlessness. Then there was motion. For a while I felt as though I were flying. Soaring. Later, I sensed a stillness which held me nearly breathless. Yet, I was unafraid.

Note that the partial sentences are used sparingly. Incomplete sentences do not fare well in large numbers or in groups. They draw their musical strength and often their meaning from the complete sentences that surround them.

So write complete sentences ninety-nine percent of the time. But now and then if a partial sentence sounds right to you, that’s what you should write. Period.

Throughout this book I will remind you that shorter is almost always better. This is an exception. It usually takes more words to show than to tell, but you can afford a few extra words for a tool this valuable.

When you show people something, you are trusting them to make up their minds for themselves. Readers like to be trusted. Don’t dictate to them what they are supposed to see, or think, or feel. Let them see the person, situation, or thing you are describing, and they will not only like what you have written, they will like you for trusting them.

Look at the following letters from camp. Letter A tells; letter B shows. Which letter do you find more revealing: Which letter writer would you rather know—Irma, or Donna?

Show, don’t tell. Even in business letters and memos.

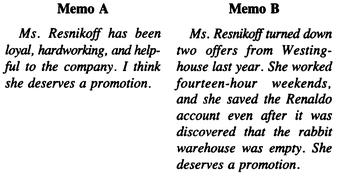

You want Barbara Resnikoff to get a promotion, but you need the board’s approval. Which memo would Barbara Resnikoff prefer to have you send?

Words that are part of the same information package are related, and they should be clustered together to avoid confusion. Adjectives should be placed near the nouns they describe so they don’t appear to be describing some other noun. Likewise, adverbs should be close to verbs they modify, and dependent clauses should be near the words on which they depend for meaning.

Though several consecutive sentences constructed the same way can bore the reader, there are times when you should deliberately arrange words and sounds in similar fashion in order to show the reader the similarity of information contained in the sentences. Just as the steady beat of a drum can often enrich a melody, the repetition of a sound can often improve the music of your writing. This is called parallel construction.

BOOK: 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series)

10.94Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Matter Of Trust by Lisa Harris

A Long Time Dead by Sally Spencer

Her Notorious Viscount by Jenna Petersen

Attack on Phoenix by Megg Jensen

Whiskey Kisses by Addison Moore

Honeysuckle Summer by Sherryl Woods

Alone in the Crowd (The Chronicles of Anna Foster Book 3) by Patrick Stutzman

Almost Always: A Love Unexpected Novel by Adams, Alissa