Read 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series) Online

Authors: Gary Provost

100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series) (11 page)

BOOK: 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series)

2.39Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

This book is full of examples. I say that something is true, and then I show you an instance of it being true. Because this is a teaching book, many of the examples are long. But examples are usually short in writing. Often they are tacked on to the end of a general statement. They do a lot of work, and they impress readers. Examples are used to back up your statements. They clarify your generalizations and help to prove that you are right. Finally, they show the reader what, exactly, it is that you’re talking about.

Below is an example from

Weight Watchers

(April 1982) that shows how I helped prove a point I’d made about foot care.

Weight Watchers

(April 1982) that shows how I helped prove a point I’d made about foot care.

Most non-specialists don’t know much about foot care and that can lead to trouble. For example, Jed Norin’s bone spur was originally misdiagnosed as a wart by a general practitioner.

If your reader works in the downtown area of Austin, Texas, and you write that an earthquake will devastate downtown Austin on February 19, your reader is going to be extremely interested to know where you got your information.

If you mention that you learned of the upcoming earthquake from Ramona Moon Dobbins, a Louisiana swamp witch who saw the whole thing in a vision while she was shuffling her tarot deck, your reader might not be too concerned. But if you mention that your information came from Dr. Winston Ruxbacher, Director of the United States Seismographic Study, your reader might decide that February 19 would be a real good day to skip work and visit an aunt in EI Paso.

Your reader’s reaction to your information depends on your sources.

Sources are the people you talk to and the literature you read while researching your story. You could mention all your sources in your article or paper, but if you do, you risk losing your reader’s attention. Lists of sources can become very boring very quickly.

Decide who or what are your most valuable sources, and name only them. Good sources help build credibility and take on added importance when you are contradicting widely held assumptions, or when a crucial decision depends on your accuracy.

You can note sources informally in the text, or you can include a note on sources at the front or back of your story. Such a note appears below:

SourcesIn-depth interviews with Alexander Millis, President, National Wenfronckmonkin Institute, and Randy Freidus, host of the nationally syndicated television show,

Your Wenfronckmonkin and You.Zen and the Art of Wenfronckmonkin

by Jim BellarosaWenfronckmonkin in the New Age

by Gloria Bunker“Wenfronckmonkin: A Male Perspective,” article in

Macho

magazine, June 1983

Again, don’t include every book you read and every expert you spoke to, just the major sources of information.

You should also include the source of opinions expressed in your story.

If you are expressing your own opinion in a story, don’t try to hang it on the vague “There’s a growing feeling” or “Widespread opinion is.” But neither do you have to precede every sentence with “I think” or “It’s my opinion that.” If you write, “Sturge Thibedeau is the worst director in Hollywood,” that is obviously your opinion, since it is not a measurable fact.

But if you’re going to disown the opinion and write something like “Sturge Thibedeau is generally considered to be the worst director in Hollywood,” back it up with something like “In a 1981 poll of one hundred top directors, ninety-seven rated Sturge Thibedeau as the worst director in Hollywood or anywhere else.” If you can’t back the opinion with something, then you have to wonder about where you got the idea in the first place.

I’m not trying to improve your ethics, only your writing. A phrase like

widely regarded

means nothing to the reader unless he or she knows what you mean by

widely regarded.

Does

widely regarded

mean the writer and his brother? Does it mean three bad actors who got canned from Thibedeau’s films? Does it mean Sturge Thibedeau’s ex-wives? Or does it mean one hundred knowledgeable people in the film industry?

widely regarded

means nothing to the reader unless he or she knows what you mean by

widely regarded.

Does

widely regarded

mean the writer and his brother? Does it mean three bad actors who got canned from Thibedeau’s films? Does it mean Sturge Thibedeau’s ex-wives? Or does it mean one hundred knowledgeable people in the film industry?

Useful information is information that has “service value.” That means readers can do something after they read what you have written. They might bake a cake because you gave them a recipe, or they might start getting in shape because you gave them directions for ten exercises. Useful information is often nothing more than a list of places, dates, addresses, or routes. It’s not the kind of thing that marks the writer as the next Tom Wolfe, but it is the kind of thing that will make your writing saleable.

“Familiar quotations,” wrote Carroll Wilson, in the preface to a book of quotations, “are more than familiar; they are something part of us. These echoes of the past have two marked characteristics—a simple idea, and an accurate rhythmic beat.”

Though “quotation” and “quotes” are the same thing, we generally think of quotations as words that are notable enough to have been preserved through time.

Use quotations when you need to enhance an idea with something poetic or reinforce a generalization or an opinion.

Quotations will create the idea that you are not alone in your opinion, that somebody, perhaps even Abraham Lincoln, agrees with you. They will give you credibility by association.

Don’t use a lot of quotations, however, or they will look more like crutches to hold you than planks to support you.

How do you come up with good quotations? The most famous source is

Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations,

but there are a variety of paperback and hardcover books of quotations. Some are arranged by topic, some by author, some by both. Browse in the bookstore. Also, when you hear a quotation you like, write it down. Here’s how you might use a quotation:

Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations,

but there are a variety of paperback and hardcover books of quotations. Some are arranged by topic, some by author, some by both. Browse in the bookstore. Also, when you hear a quotation you like, write it down. Here’s how you might use a quotation:

“Hold fast to dreams for if dreams die, life is a broken winged bird that cannot fly.” The words were written by Langston Hughes, but they have special meaning today for Sturge Thibedeau. Thibedeau, who has long been considered one of Hollywood’s worst directors, achieved his lifelong dream yesterday with the release of

Treadmill to Oblivion.

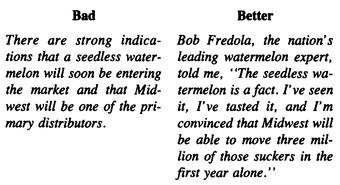

Quotes are the words someone said to you when you interviewed her for your story, or short excerpts from some of the reading you did in your research. Quotes in your story will attract readers. The white space surrounding the quotes makes the typed or printed page less intimidating. And, more important, quotes create credibility.

In an article in

Esquire

called “The Height Report,” writer Ralph Keyes provided his readers with a lot of nuts-and-bolts information to prove that tall men land better jobs, make more money, and are generally more successful than short men. Here are two examples of how he made those facts stronger and more credible by seasoning his article with quotes from various tall people.

Esquire

called “The Height Report,” writer Ralph Keyes provided his readers with a lot of nuts-and-bolts information to prove that tall men land better jobs, make more money, and are generally more successful than short men. Here are two examples of how he made those facts stronger and more credible by seasoning his article with quotes from various tall people.

John Kenneth Galbraith says he’s experienced his tallness as a competitive asset on the job market. At 6’ 8.5” he explains, “My height gave me a range of opportunity that I would never have had otherwise, because people always remember the guy whose head stands high above the others when they are trying to think of somebody for a job.”“You send over two people who are equally qualified,” the Wall Street recruiter explains, “and they’ll pick the taller, bener-looking guy every time.”

Quotes must be used judiciously. You can’t just hang one up every time you want to cover a hole in your story. Use a quote when the speaker’s words will achieve your goals more effectively than your own words.

The people you interview often say things that are provocative, informative and entertaining. However, they rarely say those things in a concise way. They ramble. They repeat. They reiterate.

If you quote people word for word, most of your quotes will be tedious and half of them will be incomprehensible. Unless national security is at stake, trim your quotes down to the words you need. It is perfectly appropriate to cut the fat from interviews and present to the reader only the meat of what the speaker said. However, cut carefully. A carelessly cut quote can change the meaning of the speaker’s words. You must remain true to the spirit of what was said, if not the form.

A good title will make a reader curious.

A good title is a guide. By telling something about the content of your story, it separates the appropriate readers for your story from those who would have no interest in it.

A good title is short. Don’t write, “Investigative Techniques and Conclusions Concerning the Proposal to Extend Client Services.” Write, “Results of the Client Survey.”

A good title hints at the limits of information in the story; that is, it suggests the slant. Don’t write, “How Sports Enriched My Religious Life.” Write, “A Christian Looks at Baseball.”

A good title should reveal information, not hide it. Don’t write, “Tips on an Important Purchase.” Write, “Six Ways to Save Money Buying a House.”

CHAPTER EIGHT

Ten Ways to Avoid Grammatical Errors

BOOK: 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing (Mentor Series)

2.39Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

26 Kisses by Anna Michels

Hatteras Blue by David Poyer

Wolfe by Cari Silverwood

Spider on My Tongue by Wright, T.M.

Gracie by Marie Maxwell

Last Rites by William J. Craig

Epic by Ginger Voight

Imperial Guard by Joseph O'Day

Why Does it Taste so Sweet? by PJ Adams

Love & Folly by Sheila Simonson