1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (44 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Julio César Arana

Arana had incorporated his company in London in an attempt to go public and cash out, as software entrepreneurs would do a century later. It had a placidly respectable British board of directors whose members apparently believed Arana’s lies about having clear title to the rubber land and using company profits to educate tens of thousands of Indians. The slavery was therefore a British matter. Eventually there was a parliamentary investigation and a years-long public furor. London sent an investigatory team that included Roger Casement, an Irish-born British diplomat who was a pioneering human-rights activist—he had exposed atrocities committed in the Congo by agents of Belgian king Leopold II. Casement shuttled about the Putumayo, confirming Hardenburg’s charges by obtaining detailed confessions of murder and torture. In a misguided fit of nationalism, Peru defended its citizen against foreign meddling. Nonetheless Arana’s empire disintegrated. He died penniless in 1952.

3

Arana was by no means the only force trying to build a rubber empire in this area of unsettled borders. Political and business leaders in Europe and the United States were infuriated that a material so vital to their economies was completely controlled by foreigners. The result was what Hecht has dubbed the “scramble for the Amazon.” Arguing that the southern border of its colony in Guyane actually extended into rubber country, France sent troops into the forest. Brazil did the same. A standoff ensued. King Leopold II offered to settle the dispute by taking control of the rubber himself, an offer that pleased neither side. France, unable to maintain its force in the forest, gave up in 1900. Britain was more successful in claiming that its colony reached into rubber territory. Rather than resorting to force of arms, it deployed the Royal Geographic Society, which produced a scientific-looking survey—proof enough for the Italian foreign minister, who had been selected to mediate the dispute. British Guiana acquired some rubber land.

From Brazil’s point of view, the greatest threat to its dominance of the rubber trade was the United States. The U.S. interest in Amazonia dated back to Matthew Fontaine Maury (1806–73), founder of both the U.S. Naval Observatory and modern oceanography. An ardent advocate of slavery, Maury became possessed in the 1850s by the fear that the South would lose its political clout because it was not big enough to withstand the North. In a widely circulated pamphlet, he proposed a solution: the United States should annex the Amazon basin. Ocean currents push the river’s outflow into the Caribbean, where it meets the outflow from the Mississippi—proof, to Maury’s mind, that the Amazon was, oceanographically speaking, part of North America, not South America. For this reason, he argued, the Amazon valley was a natural “safety valve for our Southern States.” He sent two cartographers to map Amazonia for the future day when U.S. slaveholders would go “with their goods and chattels to settle and to revolutionize and to republicanize and Anglo Saxonize that valley.” Southern plantation owners should resettle there, Maury argued, converting the river basin into the biggest U.S. slave state. Few planters paid attention until the South lost the Civil War. Hoping to re-create slave society in the forest, ten thousand Confederates fled to the Amazon. All but a few hundred quickly fled back. The remaining die-hards formed a sort of micro-satellite of the Confederacy in the town of Santarém, in the lower Amazon.

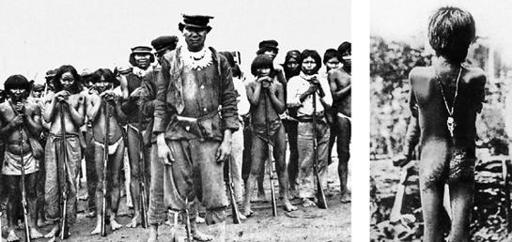

Julio César Arana controlled his private rubber domain in the upper Amazon with guards imported from Barbados (left). Unfamiliar with local people and utterly dependent on him, they enforced his every rule with immediate brutality. Laborers who failed to perform were given the “mark of Arana”—whipped until the skin fell off (right). (

Photo credit 7.4

)

With Maury, Washington gave up any idea of directly annexing Amazonia. But it was willing to try to control the rubber country through a proxy: Bolivia. Bolivia and Brazil had long contested their borders. After a short war in the 1870s, Bolivia ceded part of its territory in the south, receiving as compensation title to land to its north, around the Acre River, one of the richest areas, it later turned out, for

H. brasiliensis.

Unfortunately, all the rivers in the area—the main conduits for traffic—flowed into Brazil. It was thus vastly easier to reach Acre from Brazil than from La Paz, the Bolivian capital, up eleven thousand feet in the Andes. Taking advantage of these geographical circumstances, Brazilian tappers moved illegally across the border into Acre. Bolivia, too poor to mount an effective military response, sold the rights to Acre’s rubber to a U.S. syndicate. Now the Brazilian squatters would be taking money not from powerless Bolivians, but from wealthy, politically connected U.S. businessmen. The syndicate persuaded the U.S. government to send a gunboat up the Amazon. It was turned back near Manaus.

Angered by the move, the Brazilians in Acre attacked the Bolivian regional capital of Cobija on August 6, 1902: Bolivia’s national day. Asleep in its barracks after a drunken holiday feast, the garrison in Cobija was captured without a shot. The Bolivian army took three months to descend from the heights of La Paz, by which time the fight was over—Acre was Brazilian, the U.S. syndicate was routed, and Cobija, formerly in the center of Acre, was now a Bolivian border town. Today almost the only trace of the battle is at the airport in Cobija, where a monument at the entrance extols the “heroes of Acre.”

Victory in Acre sealed Brazil’s triumph. Having beat back almost all challenges to its control over rubber, it was producing ever more of this vital elastomer and controlling most of the trade in the rubber it didn’t produce. Hundreds of thousands of people were making a living from the forest. The situation was in many ways much like what environmentalists hoped for in the 1990s and 2000s when they argued that Brazilians should sustainably gather rubber and other forest products in the Amazon, rather than set up short-lived cattle ranches. But instead Brazil showed how these schemes can go awry.

WHAT WICKHAM WROUGHT

When the man from the rubber company came to the village of Ban Namma, men drifted from their homes to meet him. They hunkered down in their sandals and worn T-shirts on the bare ground in front of the village headquarters. Surrounding them was an asteroid belt of silent women and almost-silent children. The company agent had a sports coat and a glad-handing manner. He distributed cigarettes, snapping them from the pack with the expert flick of a prestidigitator. Villagers tucked them in shirt pockets or behind ears. The man from the rubber company told a joke and the men laughed. A moment later the women laughed.

Ban Namma straggles up a hill next to the two-lane track that is the main road—often the only road—in the northwest corner of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. It is at the edge of the Golden Triangle, the intersection of the borders of Laos, Myanmar (formerly Burma), and China, a region long infamous for its opium and heroin. Some of the biggest producers were the brutish descendants of the Nationalist military officers who fled Mao Zedong’s takeover of Beijing in 1949. They were joined and to some extent replaced in the 1960s by guerrillas from Communist uprisings in Myanmar. Because Beijing was subsidizing these guerrillas, its simultaneous efforts to shut down the Golden Triangle drug trade were, not surprisingly, less than successful. Eventually China tired of having criminal gangs on its border. In the 1990s it attacked them with a new weapon: corporate capitalism. Tax and tariff subsidies, some from United Nations anti-drug funds, pushed Chinese firms to create rubber plantations in the tiny, impoverished villages across the Laotian border. One of these villages was Ban Namma. The man with the cigarettes had persuaded its inhabitants to plant 1,325 acres of their land with

Hevea brasiliensis.

The rubber man introduced himself as Mr. Chen. The venture had not been entirely successful, he told me. Rubber trees need to be planted on warm, sunny slopes that are not exposed to wind or cold and must be carefully tended for seven years before they can be tapped. In Ban Namma, Mr. Chen said, the villagers had no experience with

H. brasiliensis

and had made beginners’ mistakes. They cleared land at the wrong elevation and failed to water abundantly. The promised 1,325 acres of thriving trees had become less than 500 acres of hard-pressed trees.

Despite this kind of setback Laotian rubber was booming. For miles around Ban Namma forestland had been shaved clean at the direction of Chinese rubber firms. Young rubber trees rose like morning stubble in the cleared patches. To the far west, near the border with Burma, a big Chinese holding company, China-Lao Ruifeng Rubber, was cutting and planting almost 1,200 square miles; a second firm, Yunnan Natural Rubber, planned to convert another 650 square miles. Much more was projected, according to a 2008 report by economist Weiyi Shi for the German development agency GTZ. The area was being transformed into an organic factory, primed to pump out latex for the trucks that were already beginning to thunder down the narrow roads.

If this ecological tumult could be laid at the door of a single person, it would be Henry Alexander Wickham. Wickham’s life is difficult to assess: he has been called a thief and a patriot, a major figure in industrial history and a hapless dolt whose main accomplishment was failing in business ventures on three continents. Perhaps the most accurate way to describe his role was that he was a conscious human agent of the Columbian Exchange. He was born in 1846 to a respectable London solicitor and a milliner’s daughter from Wales. When the boy was four, cholera took his father’s life and the family he left behind slid slowly down the social ladder. Wickham spent the rest of his life trying to climb back up. In this quest he traveled the world, wrecking his marriage and alienating his family as he tried with blind tenacity to found great plantations of tropical species. Manioc in Brazil, tobacco in Australia, bananas in Honduras, coconuts in the Conflict Islands off New Guinea—Henry Wickham failed at them all. His adventure in Brazil cost the life of his mother and his sister, who had accompanied him. The coconut plantation, on an otherwise uninhabited island, was so lonely and barren that Wickham’s wife, who had endured years of privation without complaint, at last demanded that he choose between the coconuts and her. Wickham chose coconuts. They never spoke again. Nonetheless at the end of his days he was a respected man. Crowds applauded as he walked onto testimonial stages wearing a silver-buttoned coat and a nautilus-shell tie clip. His waxed moustache curved ferociously beneath his jaw like the moustache of an anime character. He was knighted at the age of seventy-four.

Wickham won the honor for smuggling seventy thousand rubber-tree seeds to England in 1876. He was acting at the behest of Clements R. Markham, a scholar-adventurer with considerable experience in tree bootlegging. As a young man, Markham had directed a British quest in the Andes for cinchona trees. Cinchona bark was the sole source of quinine, the only effective antimalaria drug then known. Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, which had a monopoly, zealously guarded the supply, forbidding foreigners to take cinchona trees. Markham dispatched three near-simultaneous covert missions to the Andes, leading one himself. Hiding from the police, almost without food, he descended the mountains on foot with thousands of seedlings in special cases. All three teams obtained cinchona, which was soon thriving in India. Markham’s project saved thousands of lives, not least because Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia were running out of cinchona trees—they had killed them by stripping the bark. Riding the success to the position of director of the India Office’s Geographical Department, Markham decided to repeat with rubber trees “what had already been done with such happy results for the cinchona trees.” British industry’s dependence on rubber was leaving the nation’s prosperity in the hands of foreigners, he believed. “When it is considered that every steam vessel afloat, every railway train, and every factory on shore employing steam power, must of necessity use india-rubber,” Markham argued, “it is hardly possible to over-rate the importance of securing a permanent supply.” Glory would attach to those who secured that supply. In the early 1870s Markham let it be known that Britain would pay for rubber seeds. When the seeds arrived, they would be sown at the Royal Botanic Gardens, at Kew in southwest London, and the successful seedlings dispatched to Britain’s Asian colonies. Two separate hopeful adventurers sent batches of rubber seed. Neither batch would sprout. Wickham became the third to try.