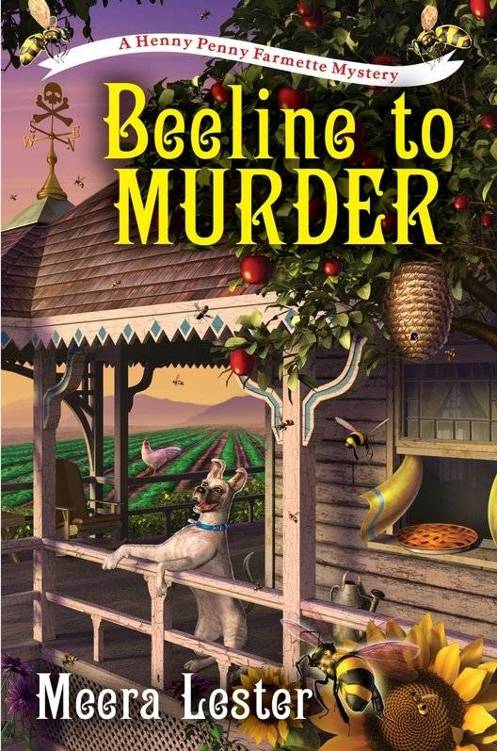

A Beeline to Murder

Read A Beeline to Murder Online

Authors: Meera Lester

A Beeline to MURDER

Meera Lester

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For my Scribe Tribe,

my readers,

and all the mystery writers—past and present—whose

books have inspired me.

my readers,

and all the mystery writers—past and present—whose

books have inspired me.

Chapter 1

A drone (male honeybee) must be able to fly fifty feet straight up, or he will miss the chance to mate with the queen; it is nature’s way of ensuring a robust gene pool.

—Henny Penny Farmette Almanac

A

bigail Mackenzie pushed the trowel deep into the soft, loamy earth where she had been planting lavender from gallon pots. She rocked back on her heels and cocked her head to one side, listening intently. The low-pitched drone could mean only one thing. Removing her gloves, Abby pushed a tangle of reddish-gold hair off her face and yanked up a hemmed corner of her faded work shirt to wipe the perspiration from her forehead. Squinting up into the dappled sunlit branches, she spotted them: thousands of honeybees writhing in a toffee-colored mass in the crotch of the apricot tree.

bigail Mackenzie pushed the trowel deep into the soft, loamy earth where she had been planting lavender from gallon pots. She rocked back on her heels and cocked her head to one side, listening intently. The low-pitched drone could mean only one thing. Removing her gloves, Abby pushed a tangle of reddish-gold hair off her face and yanked up a hemmed corner of her faded work shirt to wipe the perspiration from her forehead. Squinting up into the dappled sunlit branches, she spotted them: thousands of honeybees writhing in a toffee-colored mass in the crotch of the apricot tree.

“Arghh,” Abby groaned. “Would it have killed you to wait another day?”

The sound of honeybees swarming ordinarily would have lifted Abby’s spirits; it meant an additional hive for her growing colony of bees. But today that buzzing pushed her stress level as high as the cloudless May sky. The queen and her entourage had left the hive en masse, and unless Abby acted quickly, they would follow their winged scouts to a suitable new home, even if that home was five to eight miles away. To rescue the bees, she would have to don her beekeeper’s suit, position a hive beneath the swarm, tie a rope around the apricot limb, and shake it with enough force to dislodge the bees into the open box—all adding up to precious minutes that she would have to shave from her already over-scheduled morning.

Watching the bees coalesce into a thickening corpus, Abby pondered the remote possibility that the bees might also hang around. But, for certain, the lavender wasn’t going to plant itself. More importantly, she couldn’t postpone delivering that file to the district attorney’s office before noon if she expected to get paid for her part-time investigative work. And, of course, she had better get those ten jars of honey to the chef at the Las Flores Patisserie by eight thirty or risk another dressing-down, although the chef’s cursing in French somehow rendered it less offensive.

Blowing a puff of air between her lips in exasperation, Abby threw down the trowel. The lavender and the bees would have to wait. Chef Jean-Louis Bonheur could be a tyrant or a charmer, and his moods seemed to swing without warning. She could only hope that today he’d be happy to see her. He was paying her well—twenty-two dollars for a sixteen-ounce jar. With her first delivery of lavender-flavored honey, the chef had convinced her to also sample his delectable pastries and had even invited her to watch him work. Abby recalled how she had enjoyed the role of observer—he was definitely eye candy, with thick brown hair, large brown eyes, and a buffed physique. It didn’t hurt that he oozed personality. What woman wouldn’t fall for that combination? But Jean-Louis was gay, and his hair-trigger temper had already become legendary along Main Street. So she vowed today to skip the banter and just deliver her honey, get paid, and stick to her schedule.

After guiding the Jeep into the parking space at number three Lemon Lane, the alley behind the patisserie, which faced Main Street, Abby checked her watch and smiled. Five minutes early. Not like last time, when she’d arrived late because of a flat tire to find Chef Jean-Louis in his kitchen, pacing and swearing under his breath. He’d shocked her by throwing a pastry bag of batter that he’d been piping onto a parchment-lined baking sheet with such force, it knocked over a bowl of chocolate ganache. And later, while counting out cash to pay her for the delivery, he’d launched into another tirade, punctuating his French exclamations with incredulous glares, his hands wildly gesticulating in the air. As she hurriedly pocketed the money and made her way to back door, he’d called out an apology, or so she’d thought. His words stuck with her. “It is not you, AHbee.” She’d never get used to his pronunciation of her name. “Non, c’est Etienne. Il est en retard

.

” Apparently, she hadn’t been the only person that day to violate the chef’s obsession with punctuality.

.

” Apparently, she hadn’t been the only person that day to violate the chef’s obsession with punctuality.

Now with minutes to spare, Abby hoisted the box containing the sixteen-ounce jars of honey into her arms and scampered to the pastry shop back door, which stood slightly open.

“Chef?” Abby called cheerfully through the crack. “Chef Jean-Louis. It’s Abigail Mackenzie. I’ve got your honey order here.”

Abby pushed the box against the door. It swung open. Inside, the sudden hum of the motor of the chef’s commercial-size, stainless-steel refrigerator kicked on. The sound pierced the silence of the empty kitchen. On the long center island, metal sheets of pastries on cooling racks awaited icing, filling, and drizzling. Cream horn and madeleine molds, pastry slabs, baking liners, mats, and cannoli tubes littered the counter space. Next to a large mixing bowl of royal icing lay a pastry bag filled with icing that had hardened from its wide tip. The ovens were still on, and the burnt smell of cake permeated the room.

Abby frowned. Something was terribly wrong with this scene. Setting the box of honey on the island, she instinctively grabbed a pot holder and turned off the oven. The law enforcement training she had gone through while at the academy and during her seven years with the Las Flores Police Department had honed her senses. Now, like back in the day, when she was often the first at the scene of a crime, her stomach knotted in that old familiar way. Why would the chef leave the premises with the back door open? Why was the CD player not on, when the chef, a fan of opera, always listened to his favorite arias while he worked? And why was his workstation so messy, when the chef took great pride in keeping his kitchen clean and organized to be as efficient as possible? Where was Chef Jean-Louis?

Abby’s pulse quickened. Her muscles tightened.

What’s going on here?

Abby tensed as she looked around. “Jean-Louis,” she called. And then again more loudly, “Hello, Chef. Are you here?”

What’s going on here?

Abby tensed as she looked around. “Jean-Louis,” she called. And then again more loudly, “Hello, Chef. Are you here?”

No answer.

Abby moved the box of honey in jars over to the cupboard where the chef usually stored them, since his pantry was often overflowing with supplies. Turning back, she walked slowly to the other side of the large island and rounded the corner. Her breath caught in her throat. There lay the chef, near the pantry door—eyes open, body not moving.

“Oh, my God in heaven!” Abby knelt and felt his wrist. No pulse. She leaned against his chest, desperately hoping to detect a breath. His open eyes were dull and cloudy. The ashen pallor of his skin, the bluish-colored lips, and the nonreactive and dilated pupils told Abby he was gone. She looked for signs that would tell her

how

he’d died. Instinctively, she peered at his neck and the narrow ligature mark it bore. Her senses flew into high alert.

how

he’d died. Instinctively, she peered at his neck and the narrow ligature mark it bore. Her senses flew into high alert.

Scanning the room for any sign of movement, Abby slowly rose. So what happened here? Had he killed himself? Or had he been the victim of foul play? She glanced at the pantry door, which was not completely closed. Could a killer be hiding on the premises? Heart pounding, adrenaline racing, Abby took out her cell and tapped the speed dial for her old boss.

“Chief Bob Allen, please,” Abby said in a low voice. When he answered, she replied softly, “It’s Abigail Mackenzie. I want to report a death. It’s Chef Jean-Louis Bonheur . . . and it looks suspicious. You might want to send a unit to his pastry shop on Main. I entered through the rear, facing Lemon Lane.”

Abby stared at the pantry door. Spotting a box of latex gloves on the counter, which the staff used to handle pastries, Abby took two and slipped her hands into them. She slowly, firmly grasped the pantry doorknob. Held her breath and yanked hard. She flipped on the light switch. Seeing no one, she exhaled in relief and pivoted slightly and noticed a length of knotted twine tied to the inside knob. The loose end had been cleanly cut and lay on the tile floor. An icy shiver ran up her spine. It looked like suicide, but who’d cut down the body?

Abby understood that she’d unwittingly stumbled into a crime scene. She knew how quickly the officers could respond to a call, especially to the pastry shop, which was located just ten blocks from the police station. Police headquarters occupied the first floor of the Dillingham Dairy Building, a century-old, two-story brick building situated at the end of Main Street, next to the city offices of the mayor, the town council, and the district attorney. Abby didn’t want to contaminate the scene in any way, but her instincts told her to take in the details.

Gazing down upon the chef’s dim, unanimated eyes, their once snappy brilliance forever quelled, Abby felt a twinge of sadness. She noted that the sleeves of his chef’s jacket were rolled almost to the elbows and that his left forearm was tattooed with what looked to be an interlocked nine and six. Siren screams ended Abby’s observations. She quickly peeled off the gloves and tucked them into her jeans pockets.

A tall, blond-haired uniformed officer, her gun and nightstick holstered on her duty belt and her black boots shining, apparently from a recent polishing, stepped in through the back door. Abby relaxed and grinned. So the police chief had sent Officer Katerina Petrovsky to investigate. Kat had been Abby’s best friend since they met at the Napa Police Academy. Abby had been invited as a guest speaker when Kat was still a cadet. Finding themselves seated together during the lunch that preceded Abby’s talk and again afterward, Abby and Kat had promised to stay in touch. Later, after Kat had been hired by the Las Flores Police Department, Abby had served as her field training officer.

Before the two friends could say hello, a malnourished woman with matted gray hair and bright blue eyes banged her metal shopping cart filled with stuffed plastic bags against the wall before shuffling in through the open back door. Abby instantly recognized Dora; she was one of Las Flores’s more colorful eccentrics.

“Where’s my coffee?” she asked. “The chef always gives me coffee.”

“Not today, Dora,” Kat replied.

Abby watched Dora try to undo the covered button of her once stylish, threadbare gray sweater—the task made more difficult since Dora seemed intent on not removing her 1940s-style cotton gloves. Abby remembered meeting a much younger Dora years ago at the historical cemetery, when the nearby, newly constructed crematorium had caught fire. That was before Shadyside Funeral Home was built; before the Las Flores Creek had flooded, prompting the town council to prohibit the building of any new cemetery within city limits; and long before Dora’s chestnut-colored hair had turned gray and she had taken to sleeping at the homeless encampment beneath the bridge by the creek.

“I want my coffee.”

“The chef can’t give you coffee today,” Kat explained. “You have to leave.”

“No, he told me, ‘Later. Come back later.’ ”

“When did he tell you that?” asked Kat.

“He always tells me that.”

“Okay, well, there is no coffee today. So out you go.” The officer took Dora by the arm and escorted her through the back door.

“You should talk to her. She gets around,” Abby said when Kat had reentered the kitchen. Abby pulled another pair of gloves from the box on the counter and slipped them on.

Kat looked at her with a wary eye. “Yeah, but

usually

her conversations are with those voices inside her head, so I’ll get right on that, girlfriend, but I’d like to see the body first.”

usually

her conversations are with those voices inside her head, so I’ll get right on that, girlfriend, but I’d like to see the body first.”

“Over there.” Abby pointed to the opposite side of the island.

“And why, may I ask, were

you

here?”

you

here?”

“Delivering my honey. What else? When I got here, Kat, he was already dead, lying just like that. I swear.”

“Uh-huh. And of course you didn’t touch anything, did you?”

Abby had anticipated the question. “I promise you won’t find my fingerprints on anything here except my honey jars.”

“Good.” Kat walked over to view the body more closely. She scanned the scene, taking special note of the area where the chef lay on the black-and-white tile floor.

“No blood, no splatter, unless you count stipples of frosting,” Abby observed.

“So how did he die?” Kat asked. Unsnapping the fastener on the small pouch of her duty belt, Kat removed a pair of latex gloves. Sliding her hands into them, she knelt to look closely at the body. She leaned in to see the ligature marks on the neck. “What could he have possibly done to anyone to get himself killed?”

“Well, he could have killed himself. Take a look at the pantry doorknob . . . on the inside.”

Kat stood and walked to the pantry. “I see what you mean. So if he hung himself, who took the ligature from around his neck and laid out his body on the floor? And what did he use to stand on?”

“All good questions I’ve been asking myself,” said Abby. “Since the only chair in here holds a ten-pound bag of meringue powder, I’m guessing he didn’t use it to stand on. Maybe a café chair from the other room?”

“Yeah,” Kat said with a peculiar look. “And I guess after he hung himself, he got up and moved it back?”

“Well, someone else was here. When I arrived, the back door was ajar. Perhaps someone he knew.”

Kat’s expression grew more incredulous. “Would that be the someone who couldn’t bear to see him hanging? Or the someone who wanted to tidy up after murdering him?”

Abby chuckled. “I see you haven’t lost your sense of humor. Clearly, if he was murdered, there would have to be a motive.”

“Pretty much everyone on Main Street has experienced the chef’s temper.”

“Yeah,” admitted Abby. “Even I have felt the brunt of his temper. But he was also generous to a fault. I mean, he doled out coffee and sweets to unemployed vets and the homeless.” Abby watched as Kat surveyed the kitchen before strolling into the adjacent room, where glass display cases and small wooden café tables and chairs filled the cramped space. Fleur-de-lis wallpaper above dark wainscoting was partially obscured by the numerous black-and-white posters of Parisian scenes. Above the cash register a memento board hung slightly askew. Its crisscrossed red ribbon secured photographs of customers and friends posing with the chef.

Other books

Do Him Right by Cerise Deland

La naranja mecánica by Anthony Burgess

The Fall of Anne Boleyn: A Countdown by Ridgway, Claire

The High Calling by Gilbert Morris

Breakaway (Pro-U #1) by Ali Parker

El tesoro de los nazareos by Jerónimo Tristante

The Blood Crows (Roman Legion 12) by Scarrow, Simon

Mirrored Man: The Rob Tyler Chronicles Book 1 by GJ Fortier

Blow the House Down by Robert Baer

The Seduction Vow by Bonnie Dee