A Companion to the History of the Book (50 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

Amory, Hugh (2005)

Bibliography and the Book Trades: Studies in the Print Culture of Early New England,

ed. David D. Hall. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bailyn, Bernard (1967)

The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barber, Giles (1976) “Books from the Old World and for the New: The British International Trade in Books in the Eighteenth Century.”

Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century,

151: 185–224.

Bond, W. H. and Amory, Hugh (eds.) (1996)

The Printed Catalogues of the Harvard College Library 1723–1790.

Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

Brigham, Clarence (1947)

History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 2

vols. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

— (1958)

Bibliography of American Editions of Robinson Crusoe to 1830.

Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

Clement, Richard W. (1996)

The Book in America, with Images from the Library of Congress.

Golden: Fulcrum.

Davis, Richard Beale (1978)

Intellectual Life in the Colonial South, 1585–1763.

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Evans, Charles (1903–55)

American Bibliography,

13 vols. Chicago: Charles Evans. Completed by Clifford K. Shipton through 1800; with

Index

(vol. 14), 1959 and

Supplement

(1970) by Roger P. Bristol.

Fiering, Norman (1976) “The Transatlantic Republic of Letters: A Note on the Circulation of Learned Periodicals.”

William and Mary Quarterly,

3rd ser., 33: 642–60.

Green, James N. (1995)

At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: A Brief History of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Philadelphia: Library Company of Philadelphia.

Hall, David D. and Amory, Hugh (eds.) (2000)

The Colonial Book in the Atlantic World.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hayes, Kevin J. (1996)

A Colonial Woman’s Bookshelf.

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

— (1997)

The Library of William Byrd of Westover.

Madison: Madison House.

Honour, Hugh (1975)

The New Golden Land: European Images of America from the Discoveries to the Present Time.

New York: Pantheon.

Joyce, William L., Hall, David D., Brown, Richard D., and Hench, John B. (eds.) (1983)

Printing and Society in Early America.

Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

Remer, Rosalind (1996)

Printers and Men of Capital: Philadelphia Book Publishers in the New Republic.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sabin, Joseph (1868–1936)

Bibliotheca Americana: A Dictionary of Books Relating to America, from its Discovery to the Present Time.

Continued by Wilberforce Eames and completed by R. W. G. Vail. New York: Bibliographical Society of America.

Simmons, R. C. (1996)

British Imprints Relating to North America 1621–1760: An Annotated Checklist.

London: British Library.

Stowell, Marion Barber (1977)

Early American Almanacs: The Colonial Weekday Bible.

New York: Burt Franklin.

Tanselle, G. Thomas (1971)

A Guide to the Study of United States Imprints.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thomas, Isaiah (1970)

A History of Printing in America,

ed. Marcus McCorison. New York: Weathervane.

Winans, Robert B. (1981)

A Descriptive Checklist of Book Catalogues Separately Printed in America, 1693–1800.

Worcester: American Antiquarian Society.

Wroth, L. C. (1938)

The Colonial Printer

Portland, ME: Southworth-Anthoensen.

20

The Industrialization of the Book 1800–1970

Rob Banham

At the end of the eighteenth century the making of books was still very much a craft. Papermaking, punch-cutting, type-casting, composition, inking, and binding were all done by hand, and printing was still a process using a wooden hand press – little had changed since the end of the fifteenth century. In contrast, the period 1800–1970 was one of continuing innovation which saw the introduction of many new technologies, only the most significant of which are covered here. By the end of the nineteenth century, the process of printing books with metal type was almost entirely mechanized and, by 1970, letterpress technology was on the way out, having been superseded by phototypesetting and offset lithography. The printing, publishing, and selling of books increasingly became separate activities: by 1970, it was extremely unusual for books to be printed and published by the same company.

Many of the technological advances in printing and its allied trades during the nineteenth century were driven by the requirements of newspaper and periodical printers who needed to meet an ever-increasing demand for their products.

The Times

newspaper, in particular, was at the forefront of many new developments. There were also social changes that led to a greater demand for printed matter, all of which were inextricably linked to one another: increasing literacy rates; better education; the huge increase in the size and number of manufacturing and retail businesses; and improvements in communication, particularly through the introduction of the railway network and the penny post.

Papermaking

The mechanization of the papermaking process was crucial to the industrialization of the book: without a papermaking industry capable of supplying large quantities of paper, increases in printing output would simply not have been possible. The breakthrough was made by Nicholas-Louis Robert, who worked in the paper mill of Didot Saint Leger in Essonnes. After several experiments in the 1790s, Robert was awarded a patent for his papermaking machine in 1799. Didot felt that there were better prospects for developing the machine in England and, with this in mind, his brother-in-law, John Gamble, was sent to London. Gamble was introduced to the Fourdriniers, who were involved in the stationery and papermaking trades. They agreed to finance the project and an English patent was granted in 1801. Several improved versions of Robert’s original machine were made by the engineer Bryan Donkin. By 1807, Fourdrinier papermaking machines had become commercially viable and were able to produce more paper in a day than a single vat for hand production could make in a week. Improvements continued to be made, most notably the addition of steam-heated drying cylinders. By the 1830s, machine-made paper was commonly used in all kinds of printing, including the production of books. The printer George Clowes is recorded in 1837 as declaring that “The Fourdrinier machine had been very beneficial to the printing trade, materially reducing the price of paper and enabling them to produce books at a much cheaper price” (Clapperton 1967: 292).

By 1850, production of paper in the UK had risen from around 2.5 lb per capita in 1800 to about 8 lb (Hills 1988) and the papermaking industry was struggling to meet the demand due to a shortage of rags, the main raw material of traditional Western paper. This led to a search for other materials from which paper could be made. In 1854,

The Times

offered a reward of £1,000 for the invention or discovery of a cheap substitute for cotton and linen rags. In the UK, the answer to this problem was to use esparto grass, which was imported from southern Spain and North Africa. During the two world wars supply lines were cut and so straw was used for papermaking instead. Numerous experiments were made in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which attempted to make use of wood pulp in papermaking, some mechanical, some chemical, and some a combination of the two. By the end of the nineteenth century, a significant amount of paper was being made from wood pulp. In the twentieth century, this became the primary source of material for papermaking and the amount of paper produced increased enormously – the amount of wood pulp imported into the UK increased from 79,000 tonnes in 1887 to 2,738,000 tonnes by 1970 (Hills 1988). Paper made from esparto grass and wood pulp is not as strong as rag paper, but these substitute materials allowed virtually unlimited production of low-cost paper which greatly reduced the unit cost of books and other printed items.

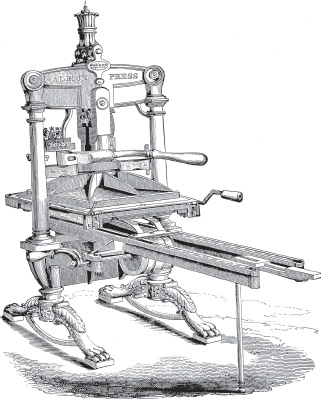

New Presses

The first significant improvement on the wooden hand press was the introduction of a new iron press, invented by Earl Stanhope in around 1800. Several other iron presses followed the Stanhope, of which the Columbian and Albion were by far the most successful. The Albion (

figure 20.1

), patented in 1820, was the English answer to the Columbian, which had been brought to England from America by its inventor George Clymer in 1817. The iron press had several distinct advantages over the wooden press. It required less physical effort to use but delivered much greater pressure, more evenly, with a much larger platen. The increased platen size meant that large forms could be printed in one pull, whereas the wooden press had required two. The new iron hand press soon became popular with book printers, but in reality the superior power made little difference to them. The iron press was faster but not significantly so and, while the extra power would have made printing easier, it had a much greater impact on jobbing printers as it allowed them to print posters with large, heavy display type.

Figure 20.1

The Albion press. From J. and R. M. Wood,

Specimens of Polytype Ornaments,

c.1855 (St. Bride negative 513).

However, the added power of the iron press did mean that it was better suited to printing wood-engraved illustrations. Early illustrated books employed woodcut illustrations, which had the advantage that they were cut in relief so that the blocks could be printed together with the metal type. Woodcut images were rather crude, although in the hands of a great artist, such as Albrecht Dürer, a much more sophisticated effect could be achieved. Later, copperplate images, which provided a much greater level of detail, were preferred to woodcuts. This was a much slower and more expensive process - the copper plates had to be printed separately from the type on an intaglio press. A happy medium was found in the late eighteenth century when Thomas Bewick improved and popularized the technique of wood-engraving. Wood-engravings were produced by working on the end grain of a piece of hard wood, such as box, with tools similar to those used by copper engravers. This meant that much finer lines could be cut than could be done with woodcuts where a knife was used to cut into the side of a plank of wood. Wood-engraving was still not as fine as copperplate but, as a relief process, it could be printed together with the type and quickly became a popular means of illustrating books, newspapers, and magazines.

Wood-engraving remained very much a craft and the only way of increasing the speed of production was by having illustrations engraved piecemeal. Large illustrations had to be made up from a number of small blocks bolted together because trees that provided suitable wood for engraving did not usually grow large enough to provide woodblocks much bigger than 120 × 170 mm (5 × 7 inches). Each of the component blocks could be engraved by a different worker to speed up production. However, technology was developed which allowed duplicates of blocks to be produced by stereotyping or electrotyping (see below) so that multiple copies could be printed at the same time, on different presses or by different printers.

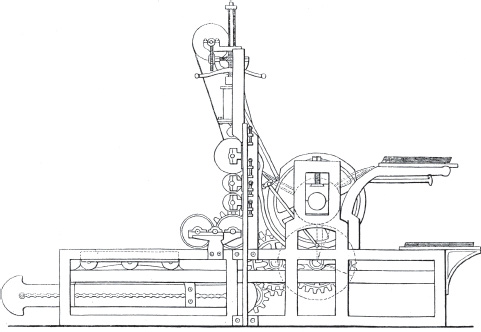

The first mechanized printing presses followed hot on the heels of the iron hand press. Friedrich Koenig, a German engineer living in the UK, began experimenting with steam-driven presses soon after the Stanhope press had been introduced. Initially, he attempted to apply steam power to the platen press but he soon switched to modifying the cylinder press used by copperplate printers which provided a simpler and more efficient means of applying pressure to the form (

figure 20.2

). Soon machines built by Koenig were installed at

The Times,

which triumphantly announced the first issue to be printed on a steam-powered press on November 29, 1814.

Koenig’s machines printed 1,100 sheets an hour compared with around 300 sheets an hour on an iron hand press, but they cost £900, almost ten times as much as the Stanhope, and it appears that this was prohibitive for most book printers. By the 1830s, some large book-printing firms were running steam presses. However, for most book printers, smaller, hand-powered cylinder presses remained the norm until the middle of the nineteenth century at which point they began to move over to steam presses that were specifically developed for book printing (such as the Wharfedale).

A series of improvements to Koenig’s press were made by Edward Cowper and Augustus Applegath, who were employed by

The Times

after Koenig returned to Germany. Although presses had been mechanized, the paper was still fed into the machines by hand in the form of single sheets (these were easier to tax and stamp than rolls of paper). In response, Applegath built a new press with four feeding stations that printed four sheets during one movement of the form and produced over 4,000 sheets an hour.

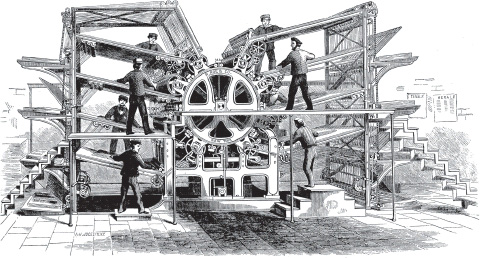

Newspapers and periodicals continued to drive the development of printing machines. Output was increased when Applegath constructed a vertical rotary press in 1848 which marked the first move away from a flat bed of type and significantly increased the speed of production. This was further improved in 1858 with the introduction of horizontal rotary presses imported from America. These huge machines, produced by R. Hoe & Co., had up to ten feeding stations and were capable of up to 20,000 impressions an hour (

figure 20.3

). Applegath’s rotary press still used flat forms of type – his “cylinder” was in fact a polygon with flat sides that carried columns of type – and early Hoe machines employed a special means of securing ordinary printer’s type to the cylinder.

Figure 20.2

Koenig printing machine of 1811. From T. Goebel,

Frederick Koenig und die Erfindung der Schnellepresse,

1906 (St. Bride negative 182).

However, soon after

The Times

introduced the Hoe machine, successful trials were undertaken to print from curved stereotype plates (see below) and by 1870 new machines had been installed that took advantage of this technology. During the 1860s, the problem of having to feed paper in by hand was finally solved by the abolition of paper duty in 1861 and by the introduction of web-fed machines that could print on both sides of a continuous reel of paper. By the end of the century, folding and cutting mechanisms had been added to machines that could produce 24,000 copies of a complete newspaper in an hour. Throughout this period of relentless advances in newspaper printing, the book trade continued to limp along behind (

figure 20.4

). Most book printers used presses derived from Koenig’s designs but, toward the end of the nineteenth century, some paperbacks were being printed on either sheet- or web-fed rotary presses. Little changed in the twentieth century except that presses were driven by electricity rather than steam, and on sheet-fed presses vacuum suction was introduced to feed the sheets in automatically.

Figure 20.3

Hoe’s eight-cylinder printing machine. From

Typographic Messenger,

September 1866 (St. Bride negative 313).