A Company of Heroes Book One: The Stonecutter (10 page)

Read A Company of Heroes Book One: The Stonecutter Online

Authors: Ron Miller

“Then you have a way...?”

“Do not have a mind about it. I will send Henda to wake you. My home is yours tonight.”

And without another word, the gypsy leaves the wagon, Henda following closely behind. The thick wooden slab of a door closes gently behind them.

“Did you see the kid’s face?” asks Thud. “How can somebody do that to a kid? Gave me the creeps, I tell you.”

Bronwyn lowers the iron bar across the door. She returns to where Thud lounges on the built-in bed, and sits beside him, drawing her legs up onto the cushion and resting her chin pensively on her knees.

“Thud, my worthy friend, I think we’re both learning that there’s a lot more about the world than we ever thought possible.”

“What do you think the gypsy meant about my picture? Do you think he can tell my fortune? I’ve never seen a gypsy before, but I heard they can tell people’s fortunes. How do you think they do that?”

He got no answer from the girl, other than the soft purring of her breath. She is fast asleep, her head against Thud’s broad hip, her hair spilling over his lap. Thud sighs. He leans his own head into the corner of the nook; his hand laying gently over Bronwyn’s head, a hand so large it seems to engulf it like a pink starfish devouring a clam. The big fingers gently stroke the hair above her ear and soon he, too, is asleep.

It is still dark when a rap came at the door. Thud, as usual, is instantly awake. Bronwyn is still asleep; her head looks like a russet cat curled in his lap for a nap. He shakes her shoulder,

“Princess? Princess? It’s time to wake up.”

Another light tap at the door. Bronwyn sits up, blinking and rubbing the sleep from her eyes, as Thud goes to the door.

“Yes?” he asks it.

“It is me,” comes the voice of the gypsy, “and Henda. It is time to leave. May we come in?”

Thud throws back the bar and the door swings open. The gypsy and the boy enter, shutting the door quickly behind them.

“Good morning, my friends. I hope that your sleep was pleasant, if unfortunately too brief.”

“Was I even asleep?” asks Bronwyn, who aches in every bone and whose eyes seems filled with powdered glass.

“I hope so. It will be dawn in an hour. We are late in leaving, but none of the others wished to disturb you so soon. Now, however, we must hasten.”

“What do we have to do?”

“Trust us.”

The four exited the caravan. The sky is blushing with the suggestive promise of dawn; the air is crisp and damp. A dozen people are busy in the plaza, puffing white vapor into the cold air; the paper lanterns are gone, the grass has been combs of every scrap of litter, the cooking and campfires has vanished. The iron tripod, its kettle, the folding stools and benches are all gone as though they has never existed; the strips pavilions of the fortuneteller and sideshow have collapsed upon themselves, disappearing like a magician’s card trick. The other gypsies, male, female and young, barely spare Thud and Bronwyn a glance.

“You are lucky, my friends, that the dancing bear died. I did not know about you, Thud Mollockle; you might have presented me with a difficulty, no?”

Thud does not know what the man is talking about and keeps quiet. The gypsy leads the two to a wagon that has large barred openings in its sides. These are normally hidden by a pair of large, hinged panels that are now swung up like wings. It is an animal cage, though presently unoccupied. The frame of the wagon is as floridly decorated as the others. As they approach, a gypsy is harnessing a brace of small, shaggy horses to the wagon tongue. They look at the strangers with sleepy, doleful eyes.

“This was the home of poor Gretl. Ah, how the children loved her, she was so gentle and such a fine dancer. But she was an old bear and three days ago, in the night, she died, just like that. We loved her, old Gretl, but what can we do with a dead bear? She was as big as you, friend Thud. Can we bury her in the plaza? No! How can we do that to such a loyal friend? It is out of the question and no doubt also illegal. So, being a practical people, we sold her. I like to think that Gretl will be feeding many hungry children and keeping them warm with her fine, thick pelt. Also, the money we were paid will be keeping a company of excellent gypsies honest and fat. Would Gretl have asked for more? I see you agree!”

They has circled the empty wagon. The horses had in the meantime been harnessed, as similar animals had been, to all of the other wagons. These are beginning to be pulled into a rough line, guided by gentle flicks from the drivers’ whips and encouraged by lilting words in the gypsies’ musical language. It is apparent that the band is anxious to depart.

“Hottl!” cries their gypsy friend to the driver of the empty bear wagon. “These are our new companions; do you have the coat?”

The man called Hottl gives Thud and Bronwyn a curt look, turns, reaches behind his seat and pulls out what at first the girl thinks is some sort of large, limp animal. It is the biggest fur coat she has ever seen. The driver hands it down to the gypsy leader, who in turn hands it to Thud.

“Put that on,” he orders.

Thud slips his arms into the sleeves. Bronwyn is amazed: the coat is actually a size too large! What kind of person has it been originally made for? It is shaggy, moth-eaten, balding, mangy and so long that its hem brushes the ground. Bronwyn giggles, a rather startling sound for her to make.

“What’s so funny?” Thud asks.

“Nothing! I’m sorry, but you really

do

look like a bear!”

Hottl next tosses a furry ball to the gypsy, who hands it to Thud. It is a hat, with long flaps that hang down on either side, like the ears of a spaniel. They hug his head when Thud ties them under his chin.

“Wonderful!” cries the gypsy. “How I wish Gretl are still here to see you!”

“You think it looks good?” asks Thud, straining his neck to see himself.

“Inexpressibly handsome! Now quickly, into the wagon.”

The gypsy unlatches a padlock as large as Thud’s fist and swings open the rear gate of the wagon. Thud clambers in, his broad hips just scraping through in a shower of brown hair. The wagon’s springs groan.

“Stay in the corner, keep your back to the gate; if anyone looks in, growl. Can you growl?”

“Grr,” growls Thud.

“I knew you could! Now,” says the gypsy, closing and relocking the gate, “we will tend to the princess.”

He unties the cords that hold up the wing-like side panels. He lets the cords run through their pulleys and the panels slam shut.

“Thud?” he calls to the interior as he fastens the wings down.

“Grr!”

“Good! Do not do anything until you hear from me or the princess again; understand?”

“Grr!”

“Quickly now,” he says, turning to the girl, “come with me.”

“What are you going to do?” she asks, trotting a step behind. She really hates the way the gypsy insists on ordering her to do things; he is worse than Thud, who at least tacks a “please” onto his requests. She doesn’t take orders; this is a matter she wants very much to call to his attention, since this habit is gradually making her angry. But he is making everything happen too quickly!

“You I shall make invisible!”

The gypsy and the princess enters the rear of another wagon. It is obviously used to carry all the paraphernalia the gypsies need for their shows and daily life; it is packed with baskets, boxes, bags, coils of rope, lanterns, sacks of feed, meal and flour, canned foods, clothing and a seemingly endless quantity of unidentifiable objects.

“Wait right here,” commands the gypsy as he disappears back into the outside daylight. Bronwyn can hear his deep voice giving orders to his band. He sounds like an iron bell when he spoke in his native tongue. He has apparently given the command to start the procession: she can hear whips snapping, ponies nickering, and suddenly her own wagon gives a jolt and begins moving, its iron-shod wheels rumbling on the cobbles. She wonders what in the world he might have planned for her. She does not much relish the thought of being disguised as an animal. The door flashes daylight at her again, and the gypsy climbs back inside. He shuts the door and the interior is once again plunged into twilight. From around the shutters that ineffectually seal the windows, thin blades of light slice through the dark.

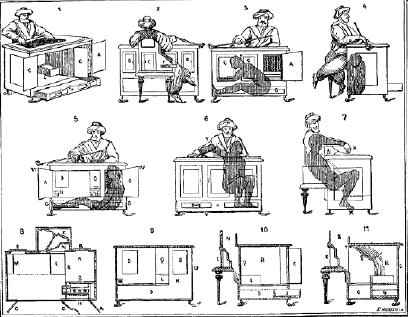

“Pardon me, please,” begs the gypsy, as he struggles to get behind the princess. He pulls a cloth away from a large object and Bronwyn gives a little gasp of surprise and delight. Revealed is a splendid Peigambarese sultan, a pudgy little man with a hooked nose and black eyes. Above the grinning mouth is a pair of long, pointed mustachios, like the quivering antennae of an insect. A dart-shaped goatee hangs from his pendulous chin. The head is topped with a jeweled turban, the body wrapped in a silken robe. The figure sits with its legs crossed, the toes of its silk slippers flamboyantly curled in full circles. Its hands, the fingers buried beneath an encrustation of jewelry, lay idly on a chessboard that is balanced on its lap. One holds the long, curved stem of a clay pipe. He has been artfully carved entirely from wood, painted and decorated with real clothing and paraphernalia and the princess, who has been that sort of girl who had never in her life owned a doll, is absolutely enchanted. The figure sits cross-legged on top of an ornately decorated box. This is about three feet high, four wide and three deep. In the front are two panels. The gypsy opens these, which comprise almost the entire façade of the box, by sliding one over the other. The inside, in the half Bronwyn can see, is filled with machinery. The gypsy opens another sliding door in the rear of the box, opposite the one in front. Now she can see entirely through the mass of gears, cams and springs to the face of the gypsy grinning amongst the gleaming machinery, like a tiger in a jungle of brass and steel.

“It’s beautiful,” says Bronwyn, with genuine admiration, though failing to see the point. “But what is it? Why are you showing it to me?”

“Ah! It is the most wonderful thing! He is really a star, this Peigambar sultan. Everyone wants to see him, and everyone who does must pay their ten poenigs to be sure. But does he want much? Does he eat like poor Gretl does, bless her soul, if bears have souls, and why should they not? No! Does he demand more than his share of the profit, because the people love him the most? No! In fact, he asks for nothing at all! Except perhaps a drop of oil now and then. Ah, I love my gypsies, but I also love my fat little Peigambar sultan!

”But what does it...he...it do? What’s the point of this?

“He plays chess, my Princess! He plays like a master! Anyone is welcome to play against him and see if he does not, but they must pay for the privilege!

“It’s a mechanical chess-player?” asks the girl, interested in spite of herself, if still mystified. “Ah, now I must be sad because I must tell you a great secret.”

While he spoke the gypsy has been turning a handle on the side of the box. A soft whirring sound, like beating wings, came from inside. He pulls a lever beside the sultan’s knee and the inside of the box comes to life. The machinery begins turning with a pleasant, soft metallic purring. Bronwyn bends to get a better look at the spinning works; it looks immensely complicated.

“Make it work!

“Come around to this side, please.” Bronwyn sidles between the figure and the piles of stores that crowd it until she can see the back of the sultan. “Watch!” The gypsy shuts the sliding panels, then touches some hidden lever or button, and the back of the sultan hinges open, the door cleverly hidden by folds in the figure’s dress. The interior of the figure is hollow. “This is Henda’s job,” explains the gypsy. “It gives him great pleasure. He is a very intelligent boy but, as you might understand, very shy with strangers. It pleases him to be shut up inside the sultan where he can see others while they cannot know he is watching. I think it gives him pleasure, too, to know that he is tricking the very people who once laughs at his face or turns away in disgust. But I will not ask him and you should not either. You noticed that I had to shut the sliding panels before I could open the sultan? Good! That is one of the secrets. I can open either one side of the box or the other, but not both at the same time. I can open the back of the sultan, but not when the front panels are open. You are looking bewildered, Princess! Let me tell you what our villager sees once he has paid his ten poenigs admission.

“When I bring the sultan before him, Henda is inside. I open one side of the box. I go to the back and open it, too. I hold a candle behind so that the villager can see the light through the machinery. Henda, he has swung his legs to one side, into the closed half of the box. I then slide the panels and do the same for the other side. Henda, he does as before. I close these and open a big door in the chest of the sultan, I open his back. The villager, he can see that the sultan has nothing in him but a few wires, rods and springs. Henda, he has dropped into the box below, bent over as far as he can. I close everything up and invite the villager to a game. Henda raises his head just far enough into the sultan to see the board. Do you see that big jewel in the chest? Look closely, see? It is just paints mesh. Henda can see through it like a window. He stretches a hand into the arm of the sultan, it only needs to move from the elbow, you see?, and can move the pieces on the board with ease. It is so simple!