A Croc Called Capone (8 page)

Even Dylan was still paying attention and he normally switches off ten seconds after anyone starts to talk. Rose and Cy were all ears. A bit like Brendan himself. They were hypnotised. It reminded me of those old films about snake charmers â turbaned guys who play flutes and the snake's head follows the movement of the instrument.

The gel-turbaned Brendan gave us a rundown of the history of the estuarine crocodile, also known as the saltwater crocodile â not to be confused with the freshwater crocodile, which is smaller and doesn't attack people. It seems the saltie had lived pretty much unchanged since the age of dinosaurs. The reason for this is that the saltie is a superb killing machine and has no need to adapt. Its only predator is humankind.

I could almost hear Blacky snorting in my head.

According to Brendan, the saltwater crocodile population in the Northern Territory was now very healthy, though he also said that until killing crocs was banned in the

1970

s, numbers had sunk to a dangerous level.

âThere's a proposal being considered by the government that hunting for crocs be reintroduced. But only by big-game hunters who are prepared to pay a lot of money for the privilege. This idea has provoked much argument up here. Some say it would inject money into remote communities and would have no impact on croc numbers. Others argue it is a barbaric practice, that we should leave the crocs alone. At present, it's illegal to kill a crocodile. Unfortunately, we do get the occasional trophy hunter who is prepared to risk the severe penalties for shooting crocs â up to

$

55 000

in fines and a possible six-year jail term.'

Brendan was being so interesting I was almost prepared to forgive his hairstyle.

Then he paused. All the time he had been talking, his eyes had roamed the expanse of water. Now he fixed on one stretch of the river.

âJust checking, folks, because it's easy to confuse a floating log with a croc. But if you look out to your left-hand side you will see we have company.'

There was a mad scramble to get a good view. Brendan killed the engines and we all piled towards the boat's railings. It was difficult to see at first. Then I spotted a

V

shape in the water heading straight towards us, the tip of a snout just breaking the surface. My nerves tingled. Julie â a blonde girl around Brendan's age and dressed in those cack-coloured shorts and shirts you associate with rangers or celebrity crocodile hunters â bustled around, fishing something from an esky at the side of the boat.

âGuys,' said Brendan's voice on the

PA

. âHere comes Al. This stretch of the river is dominated by a very large male crocodile called Capone, or Al for short. And when I say he's large, I mean

large

. This guy is well over five metres. You don't get to be that size without being a ruthless hunter and also a fierce protector of your territory. No one messes with Al. Hence his name, like Al Capone of

1930

s gangster fame.'

It was difficult to get a clear view. People were elbowing each other out of the way to get a line of sight. Rose and Cy were elbowing each other with

considerable

enthusiasm. Dad pulled me in front of him.

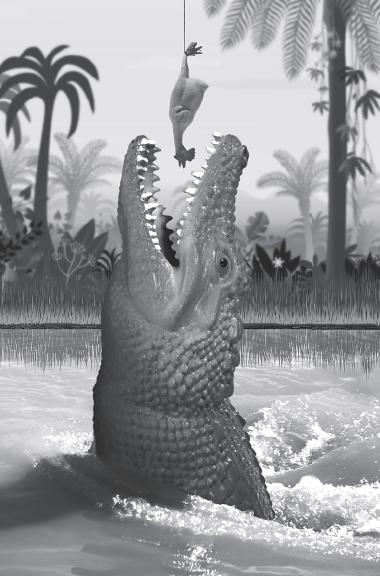

âYou might have noticed that Julie is putting a chicken on the end of a rope, attached to a pole,' Brendan said. âWhen Al comes alongside, Julie will dangle the chook and, hopefully, Al will jump to get it. Saltwater crocs jump when necessary in the wild to get prey, so we're not doing anything “unnatural”.'

I could hear the speech marks in his voice. He was probably doing that annoying finger-twirl in the air but luckily I was spared witnessing it. All my attention was fixed on Al's approach.

âMost importantly,' Brendan continued, âit's a great opportunity to get a photograph. So have those cameras locked and loaded.'

Julie brought the pole over the side and splashed the chook into the water a couple of times. Al glided closer. I could see knotty lumps along a portion of his spine.

But nothing could have prepared me for his sheer size when he glided alongside the boat. His head was huge and the tip of his tail broke the surface way off to my right.

This beast could swallow me in one gulp and I wouldn't

touch the sides of his throat. Judging by the silence all

around, the rest of our party was similarly awed. Al's eyes

were flat and expressionless but his entire body radiated

purpose. To eat. And you knew nothing would get in the

way of that.

I wrenched my eyes away for a moment. I needed Dyl next to me, to share this with him. The crowd was tight and I couldn't see past the solid wall of bodies. I glanced to my right, towards the rear of the boat. Some small movement caught my attention. I was the only one who noticed. Everyone else's eyes were pinned on Al.

Maybe Dylan had tried to force his way through the throng and failed. Maybe he'd simply gone to the one place where he could get a decent view. Trouble was, in order to do that, he'd pulled himself up onto the railings. He balanced on a thin wire, one hand holding a guideline, his body arced out over the brown water, directly above the tail of the crocodile. I saw his feet tremble on the wire.

I've read that dramatic things often seem to happen in slow motion. To be honest, I'd never believed it until that moment. I saw Dylan's left foot slip on the railing. I saw the look on his face as gravity pulled and he tried to compensate. I saw his other foot go. But everything took an age. I wanted to scream. My brain gave out instructions, but that was in slow motion as well. The sound bubbled deep down in my diaphragm. The distance to my throat seemed impossibly far. I tried to pull away from Dad towards where Dylan was toppling sideways. My muscles, like my vocal cords, were on a go-slow. I hadn't moved more than a centimetre or two before Dylan reached the point of no return.

He didn't shout, he didn't scream.

He plunged into the dirty-brown water, hitting the tip of Al's tail. Even the water arced up in a slow fountain as he went beneath its surface. The only part of the scene that wasn't trapped in a strange time warp was the crocodile.

Al Capone whipped round, the chicken forgotten. As Dylan's head broke the surface, the croc's slid beneath it.

And finally, finally, my scream made it through to my throat.

Imagine you are watching a movie on single-frame-advance and then someone presses play. That is the best way I can describe what happened next.

For the briefest fraction of a second there was stillness, a gathering of energy before explosive release. Then my scream shattered it, was joined by other screams, and there was a rush of movement down to where Dylan's head bobbed in the swell. Everything now was frantic, arms waving, voices shouting, rush, bustle, panic. But it was obvious to me â to everyone, I guess â that nothing we did really mattered. There was Dylan's head. There was a crocodile somewhere beneath the surface. Those of us safely on the boat had no power to alter events out there.

Brendan moved quickly. So did Julie. She picked up the remains of the chook and hurled it off to the left. Then she slung the bloodstained dregs in the bucket over the side. Part of me dimly understood why. She was trying to distract the croc, get the smell of blood to draw him away from Dyl. Julie thumped the surface of the water repeatedly with the pole. Nothing happened. The river's surface was broken only by her pole and the splash of Dylan's arms as he trod water. We watched, horrified, expecting any moment to see Dylan yanked from sight, his arms disappearing beneath the water, the swell fading and smoothing until all that was left was the stillness of nothing. I tried to keep his head above water by sheer force of will.

Brendan threw a lifebelt over the side and Dylan grabbed hold of it. Other adults pulled on it, dragging him to the side of the boat while Brendan slipped over the railings and stretched towards him.

âGrab my hand,' he yelled.

Even leaning out dangerously far, Brendan couldn't reach Dyl's outstretched fingers. They clawed at each other, missing by a matter of centimetres.

âPull on that lifebelt harder,' yelled Brendan over his shoulder. I saw Dad and the others straining on the rope. More joined them. I would have gone myself, but I was paralysed again. I could only stand by the railing and look into Dylan's eyes. They were strangely calm. And then, maybe two or three metres behind him, I saw the croc's head break the surface for a fraction of a second. Its eyes were calm, as well. Calm and totally lacking in mercy. They dipped beneath the surface once more.

My memories of that time are broken. They lie in pieces in my mind, so I am not sure what's real and what's imagined. But I think I saw this. I think I saw something beyond the line of sight joining Dylan's eyes and those of the crocodile â on the bank of the river, a small, dirty-white dog sitting motionless, gazing at us. Then I blinked and he was gone.

The people pulling on the lifebelt had established a rhythm now. They swayed forward and Dyl slipped back into the water. My heart hammered as I imagined powerful jaws clamped around his legs. But then the line leaned back and he surged above the surface. Brendan's hand grabbed his, slipped for a moment and then locked around his wrist. Other people wrapped their arms around Brendan's waist. They leaned back as he pulled. Dylan's body came right out of the water, his feet scrabbled on the side of the boat and then, with a rush, he fell onto the deck, tangled up with Brendan. They flopped around like fish.

I think I was the first to get to Dyl, but I might be wrong. I remember being on my knees as he struggled to get up. He looked me in the eyes. His face was pale and there were bits of rubbish in his hair â small twigs and slimy green stuff.

He grinned.

âHow cool was that?' he croaked.

I didn't answer. Instead I threw up on the front of his T-shirt.

Rose and Cy were completely hysterical. They sobbed and wailed all the way back to our cabins. Dad was deathly quiet, but I got the feeling that, given half a chance, he'd join in. Even Brendan, who'd been the calmest while the emergency was going on, was trembling as he moored the boat and helped us disembark. Julie had to drive the minibus back to the resort.

Mum, on the other hand, went straight into protective mode. True, she was badly shaken. I could tell by the way her lips were set in a thin white line. She clasped Dyl to her so tightly on the minibus you'd have needed a crowbar to pry him loose. He winked at me from the folds of Mum's dress. I tried to wink back but I was numb and my muscles wouldn't work.

The resident doctor winkled Dyl out of Mum's arms and checked him over. According to the doc, Dyl was fine physically, but it was possible delayed shock would set in. He explained that it's not uncommon for people who have undergone a really nasty experience to be fine at first and then fold into trembling blubber later when the mind finally grasps what has happened. He ordered Dyl to rest.

Dyl wasn't keen on resting. It's something he's avoided all his life. But one glance at Mum's face convinced him it might be wiser to follow instructions. Or maybe he was worried she'd do her impersonation of a human vice again. I went with him to our cabin and Mum tucked him into bed. She ran a hand through his hair.

âYou get some sleep,' she said.

âYes, Mum,' said Dyl.

Mum didn't react to his slip of the tongue. Perhaps, like me, she put it down to delayed shock.

We closed the cabin door and joined the rest of the family at the resort bar. Dad ordered something strong for him and Mum and soft drinks for me, Rose and Cy. I don't think I'd ever seen Mum drink anything other than a very occasional glass of wine. Now, she took a glass of dark amber liquid and downed it in one. Dad got her another. The five of us sat around a table and for a while no one said anything. Then Dad broke the silence.

âI think we should see about getting a flight home.'