A Fortunate Man (14 page)

Authors: John Berger

I believe that Sassall's disquiet is provoked, not by individual issues or cases because then all his attention is absorbed in âfeeling his way' and in reckoning how far he can go, but by the constant contrast between the general expectations of his patients and his own.

The average forester of over twenty-five expects, when healthy, little of life. (His extravagant expectation of fraternal recognition when ill is understandable precisely because the illness returns him to childhood, to a period before he had learned to abandon

his hopes, and when these hopes could still be reasonably satisfied within the family.) He expects to maintain what he has â job, family, home. He expects to continue to enjoy his pleasures â a cup of tea in bed, Sunday newspapers, the pub at week-ends, an occasional trip to the nearest city or to London, some form of game, his jokes. His wife has her equivalent pleasures. Both of them have fantasies which are infinitely more resourceful and rich â perhaps particularly the wife, who ages far faster. They also have their opinions and their stories to tell, and these may cover much wider ground. But what they expect in their own situation in any foreseeable future is very little: they may want more, they may believe they have a right to more: but they have learned and they have been brought up to settle for a minimum. Life is like that, they say.

Their foreseen minimum is not purely economic: it is not even principally economic: today the minimum might include a car. It is above all an intellectual, emotional and spiritual minimum. It almost empties of content such concepts (expressed in no matter what words) as Renewal, Sudden Change, Passion, Delight, Tragedy, Understanding. It reduces sex to a passing urge, effort to what is necessary in order to maintain a

status quo

, love to kindness, comfort to familiarity. It dismisses the efficacity of thought, the power of unrecognized needs, the relevance of history. It substitutes the notion of endurance for that of experience, of relief for that of benefit.

This makes them, as Sassall is always observing, tough, uncomplaining, modest, stoical. His respect for them is genuine and deep. But it does not alter the fact that his own expectations of life are diametrically opposed to theirs.

It is necessary to emphasize here that we are talking of generalized expectations rather than specific personal ones. The question is philosophical rather than immediately practical. Life is like that, the foresters say. A man may be lucky and have everything he

wants, but the nature of life is such that this is bound to be an exception.

Unlike the foresters, Sassall expects the maximum from life. His aim is the Universal Man. He would subscribe to Goethe's dictum that

Man knows himself only inasmuch as he knows the world. He knows the world only within himself, and he is aware of himself only within the world. Each new object, truly recognized, opens up a new organ within ourselves.

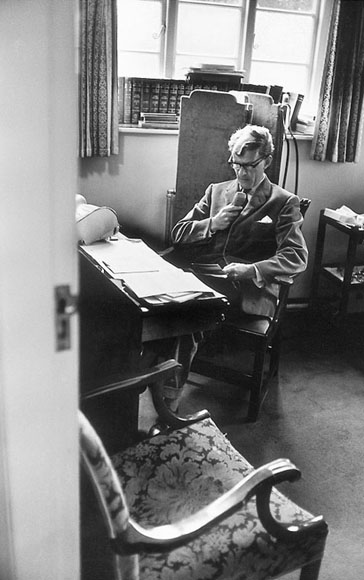

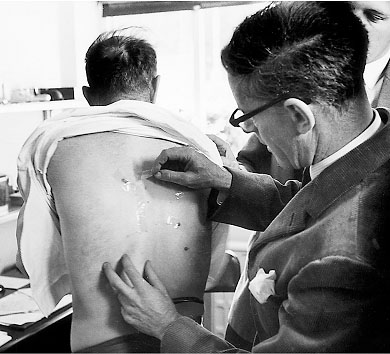

His appetite for knowledge is insatiable. He believes that the limits of knowledge, at any given stage, are temporary. Endurance for him is no more than a form of experience, and experience is, by definition, reflective. It may be that in certain respects he is prepared to settle for comparatively little â for an obscure country practice, for a quiet domestic life, for a game of golf as relaxation. (In fact on occasion he revolts even against this: four years ago he had himself accepted as the doctor and cameraman for an Antarctic expedition.) Within his outwardly circumscribed life, however, he is continually speculating about, extending and amending his awareness of what is possible. Partly this is the result of his theoretical reading of medicine, science and history; partly it is the result of his own clinical observations (he was, for example, observant enough to notice that Reserpine, given as a sedative, appeared also to cure chilblains and so might be useful in the treatment of gangrene). But above all it is the result of the cumulative effect of his imaginative âproliferation' of himself in âbecoming' one patient after another.

We can now define the bitter paradox which provokes the disquiet Sassall feels at the contrast between himself and his patients and which can sometimes transform this disquiet into a sense of his own inadequacy.

He can never forget the contrast. He must ask: do they deserve the lives they lead or do they deserve better? He must answer â disregarding what they themselves might reply â that they deserve better. In individual cases he must do all that he can to help them to live more fully. He must recognize that what he can do, if one considers the community as a whole, is absurdly inadequate. He must admit that what needs to be done is outside his brief as a doctor and beyond his power as an individual. Yet he must then face the fact that he needs this

situation as it is

: that, to some extent, he

chose

it. It is by virtue of the community's backwardness that he is able to practise as he does.

Their backwardness enables him to follow his cases through all their stages, grants him the power of his hegemony, encourages him to become the âconsciousness' of the district, allows him unusually promising conditions for achieving a âfraternal' relationship with his patients, permits him to establish almost entirely on his own terms the local image of his profession. The position can be described more crudely. Sassall can strive towards the universal because his patients are underprivileged.

From time to time Sassall becomes deeply depressed. The depression may last one, two or three months. He is not sure of the reason for these depressions. They could be organic in origin; conceivably they could be part of a still recurring but mostly hidden neurotic pattern established in childhood.

Yet if their origin is mysterious, their maintenance â if one may use the word â is revealing. By maintenance I mean the conscious material which his depressions requisition in order to justify and perpetuate themselves. With the fatal a-historical basis of our culture, we tend to overlook or ignore the historical content of neuroses or mental illness. Extreme examples in the distant past are sometimes admitted. One grants that there was a connection in the fourteenth century between the outbreaks of St Vitus's

Dance and the suffering caused by the Hundred Years' War and the Plague. But do we appreciate, for example, how much Van Gogh's inner conflicts reflected the moral contradictions of the late nineteenth century? Vulnerability may have its own private causes, but it often reveals concisely what is wounding and damaging on a much larger scale.

Sassall's depressions are maintained by the material of the two problems we have just been examining: the suffering of his patients and his own sense of inadequacy. As reflected in his depression this material is distorted, but much truth remains even in the distortion.

He is working well. In a particularly complicated case he senses the number of disparate factors involved, and begins to trace the logic of their connection. He is planning some general improvement in his practice â the acquisition, say, of a cardiograph. He feels himself master of his own experience to date. The extent of what remains for him to do in the Forest is a confirmation of the rightness of his being there. He is always observant, but in this state of mind he notices far more than he can name or explain. Everything seems significant. And the stimulus of this so speeds up his selection and application of a myriad necessary routine responses and checks that he has time to speculate about what he is doing as he is doing it. He is working creatively.

The disillusion that he is about to suffer is likely to be triggered off by a minor setback with no serious consequences at all. A serious crisis could not have the same effect, for it would engage all his attention. As it is, he becomes slightly more self-conscious than usual about his responsibility. Something has not gone exactly as he would have liked for a patient. Yet the patient is quite unaware of it. He remains grateful or continues to grumble exactly as before. It is impossible for Sassall to tell him what he feels about the setback. Not for reasons of tact or medical etiquette.

But because the patient would not understand and would still remain satisfied. Sassall is more sensitive to his patients' interests than the patient himself. He is more troubled by the setback than the patient will ever be inconvenienced by it. Thus Sassall's heightened awareness, instead of supplying him with new evidence and data â as it does when he is working well â suddenly draws attention to its own distinction. He has momentarily reached the threshold of mild paranoia. In the normal course of events the moment would pass with perhaps an ironic comment made to himself. But if at this moment he is unconsciously seeking a justification for being depressed, he can now begin to crush himself in the contradiction between his developed sensibility and the underprivileged life of his chosen patients. The challenges which have encouraged and confirmed him now seem proof of his presumption.

Guilty, he becomes increasingly susceptible to the suffering of others. This suffering, demanding its question about the value of the moment, reveals the comparative emptiness of his own life. To deny this, he tries, as we have seen, to compete with the intensity of suffering. He will work as hard as they suffer. His attitude to his work becomes obsessional.

Soon he is sufficiently depressed for his reactions to be slowed down and his power of concentration to have diminished. It seems to him that he can no longer meet the elementary demands of his practice. The challenge of what remains to be done â even the fabricated ethical basis of his obsession with work â suddenly seems to belong to another, vanished world. He believes that he cannot perform as a doctor on any level.

In fact he can and is probably still, at such moments, offering treatment which is better than the national G.P. average. But he can only partially overcome his conviction of inadequacy by admitting it. And so, to those of his patients who are in a state to be able to accept his confession, he admits his crisis. He throws

himself on the mercy of their tolerance. He depends upon the fact that their demands are minimal. The circle is complete. And, as often, the completed circle is the seal of conscientious suffering.

Sassall is nevertheless a man doing what he wants. Or, to be more accurate, a man pursuing what he wishes to pursue. Sometimes the pursuit involves strain and disappointment, but in itself it is his unique source of satisfaction. Like an artist or like anybody else who believes that his work justifies his life, Sassall â by our society's miserable standards â is a fortunate man.

It is easy to criticize him. One can criticize him for ignoring politics. If he is so concerned with the lives of his patients â in a general as well as a medical sense â why does he not see the necessity for political action to improve or defend their lives?

One can criticize him for practising alone instead of joining a group practice or working in a health centre. Is he not an outdated nineteenth-century romantic with his ideal of single personal responsibility? And in the last analysis is not this ideal a form of paternalism?

He himself is aware of the implications of such criticism. âI sometimes wonder,' he says, âhow much of me is the last of the old traditional country doctor and how much of me is a doctor of the future. Can you be both?'