A Fortunate Man (15 page)

Authors: John Berger

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

I wish I could write a conclusion to this essay, summing up and evaluating what has been noticed. But I cannot. It is beyond me to conclude this essay. I could end with another story about Sassall and perhaps most readers would then not notice the omission. It is to reasoning that the poetic gives most of its famous licence.

However, it is perhaps more to the point to analyse why the essay cannot be concluded â always assuming that the obstacles are not purely within myself.

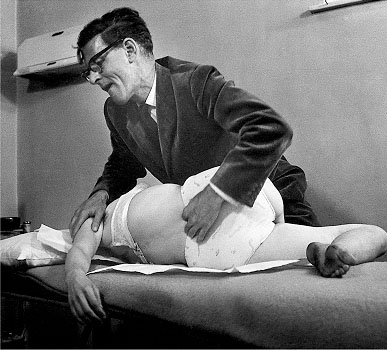

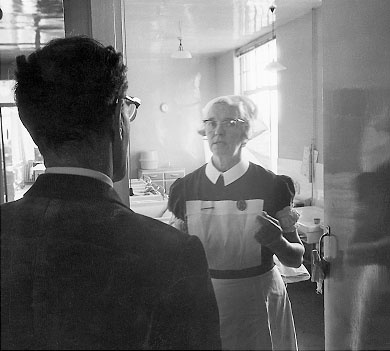

Nothing has in fact been concluded. Sassall, with the cunning intuition that any fortunate man requires today in order to go on working at what he believes in, has established the situation he needs. Not without cost, but on the whole satisfactorily. In it he is working. He is working now at this moment as I write. He may be prescribing a routine cure to a routine infection, he may be listening, taking a few drops of blood from a thumb, imagining himself to be the woman or man opposite him, talking to a sales rep from a drug firm, testing some urine, hoping to learn more, learning more.

I have described something of the situation he has established for himself: but finally this can only be judged in relation to the work he does in it. And I cannot evaluate that work as I could easily do if he were a fictional character. In a certain sense, fiction seems strangely simple now. In fiction one has only got to

decide

that a character is, on balance, admirable. Of course there remains the problem of making him so: and the effect you achieve may be the opposite of what you intended. But still â outcomes can be decided. Whereas now I can decide nothing.

I am in the exactly opposite situation to the autobiographer because he is even freer than the novelist. He is his own subject and his own chronicler. Nothing, nobody, not even a created character can reproach him. What he omits, what he distorts, what he invents â everything, at least by the logic of the genre, is legitimate. Perhaps this is the true attraction of autobiography: all the events over which you had no control are at last subject

to your decision. Now, by contrast, I am entirely at the mercy of realities I cannot encompass.

It is true that biographies, as distinct from autobiographies, are also sometimes written about living men and that these in their fashion come to a conclusion. But the subjects of such biographies are either famous or infamous. They are our future prime ministers, or the foreign politicians of whom we must take note. Both reader and writer before they begin the book know why the book has been written. It is because

X

is the famous

X

. And the story naturally concludes when he has achieved his present power, which is a form of apotheosis.

Sassall is not such a man.

And supposing he were dead? you might ask. But if he were dead I would write a different essay. It sounds absurd to say that a man's life is utterly transformed by his death, but I mean for those who knew him, or even knew of him. The simplest confirmation of this is what happens when an artist dies.

The painting you saw last week when you assume the painter was alive is not the same painting (although it is the same canvas) you see this week when you know that he is dead. From now on everybody will see the painting you see this week. The painting of last week has died with him. This may sound excessively metaphysical. Yet it is not. It is simply the result of our gift â or the necessity for us â of abstract thought. Whilst the artist is alive, we see the painting, although it is clearly finished, as part of a work in progress. We see it as part of an unfinished process. We can apply epithets to it such as: promising, disappointing, unexpected. When the artist is dead, the painting becomes part of a definitive body of work. The artist made it. We are left with it. What we can think or say about it changes. It can no longer be addressed to the artist â not even to the absent artist whom we have no reasonable chance of ever addressing; we can now only think and speak for ourselves. The subject for discussion is no longer his unknown intentions, his

possible confusions, his hopes, his ability to be persuaded, his capacity for change: the subject now is what use we have for the work left us. Because he is dead, we become the protagonists.

It is the same in life. A man's death makes everything certain about him. Of course, secrets may die with him. And of course, a hundred years later somebody looking through some papers may discover a fact which throws a totally different light on his life and of which all the people who attended his funeral were ignorant. Death changes the facts qualitatively but not quantitatively. One does not know more facts about a man because he is dead. But what one already knows hardens and becomes definite. We cannot hope for ambiguities to be clarified, we cannot hope for further change, we cannot hope for more. We are now the protagonists and we have to make up our minds.

And so if Sassall were dead, I would have written an essay which risked far less speculation. Partly because I would have wanted to write a more precise memoir of him, to preserve his likeness. But also because when writing about him I would not have been aware â as I am now and have been every moment of writing â of the process of his life continuing â unfixed, mysterious, only half conscious of its own ends. If he were dead, I would conclude this essay as death concluded his life. Without sentimentality and without religious intimations, I would have wanted him to rest, at least on these final pages, in peace.

As it is, Sassall is alive and working, and my speculations have paralleled the process of his continuing life â anxious to see the maximum possible, but inevitably half-blind, like an owl in bright daylight. Too blind to see the conclusion for certain, aware only of the alternatives.

There is another factor which makes it almost impossible to conclude this essay. It is hard to write about it without making sweeping generalizations about our society and then having to

justify these generalizations so that finally one is led too far from the subject in hand.

I must try to be simple. There are such things as national or social crises of such an order that they test all those who live through them. They are moments of truth in which, not everything, but a great deal is revealed about individuals, classes, institutions, leaders. The world at large does not usually appreciate or understand these revelations: but for all those who belong to the society or country in question their importance and meaning are quite clear. Even those who as a result of the crisis find themselves in total and lasting opposition to one another will nevertheless agree that what was revealed in the moment of truth was undeniable.

The word moments should not be taken too literally. The crisis may last for days, weeks, occasionally years. It was like this in Dublin in 1916.

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Whenever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born

.

7

It was like this in France in 1940 after the capitulation, in Budapest in 1956, in Algeria during the war of liberation, in Cuba when Castro landed for the second time in 1959.