A History of China (39 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

The decorative arts also flourished in the Tang. Tricolored ceramics, some of which portrayed foreign merchants, entertainers, and guardian figures, were especially prized. Depictions of horses and camels were similarly popular. Because many of these ceramics were buried in the tombs of the imperial family or prominent officials, some have survived intact. The 1998 discovery of a ninth-century shipwrecked Arab dhow near Indonesia’s island of Belitung, part of the maritime “Silk Roads,” attested to the existence of other kinds of ceramics and ceramic centers. Wares from Changsha and the province of Zhejiang confirm the remarkable efflorescence of ceramic production in a variety of regions in China. Depictions of a lotus (a Buddhist symbol) as well as Arabic inscriptions and central Asian motifs offer additional evidence of Tang cosmopolitanism. Ceramics constituted the majority of the sixty thousand objects found in the cargo, but gold and silver ornaments and ritual objects were also plentiful. The motifs on the largest Tang gold cup ever discovered portrayed central Asian or Persian musicians and a dancer – additional affirmation of the popularity of foreign music and dance in the Tang. The exquisite quality of these gold and silver artifacts makes art historians, in particular, sad about the loss and destruction of gold and silver ritual objects during the 840s persecution of the Buddhists. Also disappointing is the relative paucity of textiles to have survived, especially in light of the renown of the Silk Roads. Climate and the fragility of silk took their toll. A few Tang silks, including a child’s coat, have been preserved, and several reveal central Asian motifs, another indication of Tang cosmopolitanism.

OTES

1

Christopher Beckwith,

The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), pp. 146–147.

2

Pauline Yu,

The Poetry of Wang Wei

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), p. 100.

3

Marsha Wagner,

Wang Wei

(Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1981), p. 127.

4

Liu Wu-chi,

An Introduction to Chinese Literature

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1966), pp. 74–5.

5

Liu, p. 82.

URTHER

R

EADING

Timothy Barrett,

The Woman Who Discovered Printing

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008).

Charles Benn,

China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Liu Xinru,

Silk and Religion: An Exploration of Material Life and the Thought of People, AD

600

–

1200

(Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Edward Schafer,

The Golden Peaches of Samarkand

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963).

Frances Wood,

The Silk Road

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

Sally Wriggins,

The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang

(Boulder: Westview Press, rev. ed., 2003).

P

OST

-T

ANG

S

OCIETY AND THE

G

LORIOUS

S

ONG

,

907–1279

Song: A Lesser Empire

A New Song Elite

Neo-Confucianism: A New Philosophy

Attempts at Reform

Women and the Song

The Khitans and the Liao Dynasty

Expansion of Khitan Territory

Preservation of Khitan Identity

Fall of the Liao

Xia and Jin: Two Foreign Dynasties

Song Arts

Southern Song Economic and Cultural Sophistication and Political Instability

IVE

D

YNASTIES AND

T

EN

K

INGDOMS

The fall of the Tang resulted in the same kind of fragmentation that characterized the collapse of two earlier dynasties, the Zhou and the Han. No government could gain control over the entire country; instead, local rulers or dynasties prevailed. The two earlier periods of division lasted for centuries, but the fragmentation after the Tang endured for only about fifty years. Perhaps China had become simply too large to be decentralized for so long. Chaos and turbulence could not be tolerated over the vast expanse of territory that had now become part of the Middle Kingdom. The country and the growing population needed the stability that only centralized rule could provide. Or it could be that the Tang had built up such a sophisticated nexus of transport, communications, and commerce that centralization was facilitated. The indigenous Song dynasty eventually took power in much of China in 960, but was forced out of north China in 1126. The period from 960 to 1126 is known as the Northern Song, and the period from 1126 to 1279 is known as the Southern Song.

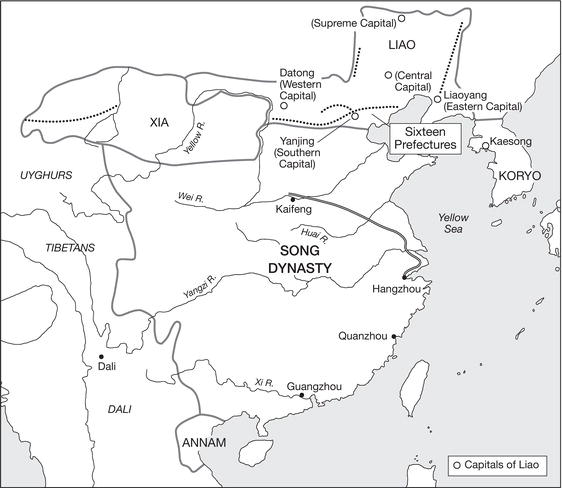

Map 6.1

Song dynasty and its neighbors, ca. 1005

Map 6.2

Song dynasty and its neighbors, ca. 1127

However, at the time of the initial collapse of the Tang dynasty, centralization and even the survival of Chinese civilization were threatened. Peoples on the northern fringes of Chinese territory capitalized on China’s weakness to occupy lands and to establish Chinese-style dynasties for the next several centuries. The Khitans, a people from Mongolia, established the Liao dynasty, which controlled the area around modern Beijing and sixteen additional prefectures in north China from 907 to 1115. Later in the tenth century, the Tanguts, a group influenced by Tibetan culture, founded the Xia dynasty, which dominated much of northwest China until 1227. Finally, the Jurchens erupted from Manchuria in 1115 and overwhelmed the Khitans, occupying much of north China and expelling the Song, the ruling indigenous dynasty, to territory south of the Huai River. Each of these groups, the Khitans, the Tanguts, and the Jurchens, did not suddenly vanish when their dynasties collapsed. Some remained in north China while others scattered throughout Manchuria, Mongolia, and central Asia and would remain in touch with China for centuries.

China’s heartland was similarly turbulent. In 907, when the Tang finally collapsed, Zhu Wen, one of the rebel Huang Chao’s underlings, was in a position to declare himself emperor of the Liang dynasty, which came to dominate north China. Yet he almost immediately encountered opposition in efforts at centralization. South China fragmented into a number of independent states, amounting to ten before China was reunited in 960. The north also did not acquiesce, and the initial recalcitrant groups, under the leadership of the Shato Turk Li Keyong and his son Li Cunxu, actually defeated the Liang in 923 and gained control over Changan and Kaifeng, two important traditional capitals. Zhu Wen himself was murdered by his own son. By 926, Li Cunxu had established the Later Tang dynasty, hoping to gain legitimacy and credibility through association with the renowned but recently overthrown dynasty of the same name. Attempting to restore centralized rule, Li sought to bring back a governmental structure similar to the Tang, with ministers, an official bureaucracy, powerful aristocratic families, and eunuchs. This mélange of potent groups resulted in the same internecine conflicts among them as in the past. Struggles within the central administration permitted provincial commanders to assert themselves and to challenge the court.

Simultaneously, however, conflicts among the commanders and between the commanders and the court weakened all sides. Warfare devastated the provinces, undermining the power of the commanders. The various dynasties themselves were also devastated because the constant tumult caused the collapse of one after another. Yet each successive dynasty recognized the need for a powerful imperial army to restrain the provincial commanders, who themselves began to weaken because of the constant warfare. It seemed only a matter of time before one dynasty, with a sufficiently potent military force, would emerge to enforce its will on the country.

Meanwhile, the south fragmented into the Ten Kingdoms, which actually endured longer than most of the northern dynasties. However, the territory each kingdom controlled was relatively finite, and none expanded beyond its original domain. Yet no single state, either in the north or south, could attract sufficient support to establish a centralized government and unified rule. However, political disunity did not prevent increasing economic relations. Interstate trade flourished because, by this time, the various regions of China had become more and more economically interdependent. Specialization of production and commerce had forged a unity that was virtually irresistible.

ONG

: A L

ESSER

E

MPIRE

The Song, under the leadership of the military commander Zhao Kuangyin (927–976), would ultimately unite the disparate states and regions into one centralized dynasty. Zhao benefited from the efforts of a few of the more competent rulers of the Han and Zhou dynasties in north China, who had enlarged the lands under their control and had begun to encroach upon the power of the military commanders. Thus, when the Song arose, conditions were propitious for an assertion of centralized authority. Zhao capitalized upon these developments to establish the Song in 960, and the dynasty moved quickly to dominate north China. Best known as Taizu (Grand Progenitor) of the Song, Zhao rapidly expanded his control into south China. By the time of his death in 976, he had incorporated the traditional centers of China, save for the states of Wuyue and Northern Han, which his successor and younger brother overwhelmed three years later. This second emperor, renowned as Taizong (“Grand Ancestor”; 939–997), ruled for another two decades and pursued many of the same policies, adding continuity to the dynasty. The relatively long reigns of the first two emperors, as compared to the brevity of rule that was characteristic of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era, contributed to the dynasty’s stability.

The accession of Zhao Kuangyin began to restore confidence in the proper operation of the Confucian system in China. He moved the capital to the city of Kaifeng, partly because Changan, the Tang capital, had been devastated toward the end of that dynasty. The Song diverged from Tang policies in order to avert the fate of its predecessor. Its officials were convinced that the Tang had fallen, in part, because of its expansionist policies and its inability to control its military forces. They thus opted to become a “lesser empire” by imposing civilian control over the military. By ruling less territory than the Tang, the court faced challenges from other Chinese states and, more important, from the foreigners who had seized lands within China. Its less expansionist and bellicose policies resulted in part from a realistic assessment of changes since the Tang. It now confronted a multistate system in northeast Asia, and it could not defeat these states, which often enjoyed military parity with the Song. It did not share the Tang luxury of being the only dominant power in the region. That is, the Song was necessarily woefully weak; its seminomadic neighbors who had established empires were powerful, and many Song policy makers took this new balance of power into account.

The Song thus tried to preserve its lands without a sizable military presence or a belligerent foreign policy and yet confronted a powerful and primarily pastoral nomadic people from Mongolia known as the Khitans, who had established the Liao dynasty. The Khitans had their own emperor, who challenged the supremacy of the Song in China proper, and their powerful military force could prove troublesome along China’s northern frontiers. Recognizing that it did not have the military capability to expel the Khitans from Chinese territory, the Song opted for a peaceful resolution of its commercial and diplomatic relationship with the Khitans. The Treaty of Shanyuan, which resulted from letters sent by the two sides in 1005, entailed humiliating concessions for the Song. The court not only promised to make annual payments of 100,000 taels of silver and 200,000 bolts of silk but also agreed that the Song emperor would address the Khitan ruler as “emperor,” not as a vassal. The treaty also demarcated the boundary between the two states and pledged both sides to peaceful relations. By signing a treaty that acknowledged the equality of a foreign state, the Song revealed its weakness. To state it perhaps too baldly, the Song bribed the Khitans in order to obtain peace. It made extraordinary concessions to deter its northern neighbor from incursions on Chinese soil.