A History of the World in 100 Objects (38 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Under the Guptas, the main deities of Hinduism and their worship assumed a form that has dominated the religious landscape of India from that day to this, and in recent years this Hindu aspect of the Guptas’ religious activities has loomed large in historians’ accounts of their reign. As Romila Thapar, Professor Emerita of Ancient Indian History at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, explains, the Guptas continue to make their presence felt in India today – not only in the monuments left behind, but also in the way the period is used politically:

When colonial history began to be written, when there was nationalist historical writing, the Gupta period was latched on to as the ‘golden age’. In the last few decades there has grown in India a way of thinking which has been called Hindutva, which is an attempt to suggest that the only person that has legitimacy as a citizen of India is the Hindu, because the Hindu is supposed to be the indigenous inhabitant. Everybody else – the Muslims, the Christians, the Parsees – all came later and came from outside. They were foreign. Never mind the fact that 99 per cent of them are of Indian blood. The Gupta period then came in for a great deal of attention as a result of this kind of thinking.

The BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, the Neasden Hindu temple, rising out of the London suburbs

This seems surprising. As these two coins show, although the Guptas established temple Hinduism in something like its modern form, they also honoured older religious traditions, and, far from being exclusive, were generous protectors of both Buddhism and Jainism. In short, Kumaragupta takes his place in the great Indian tradition inspired by Ashoka, the Buddhist king of 600 years earlier – a tradition that sees the state as tolerant of many faiths, later embraced by the Islamic Mughal emperors, by the British and by the founders of modern India.

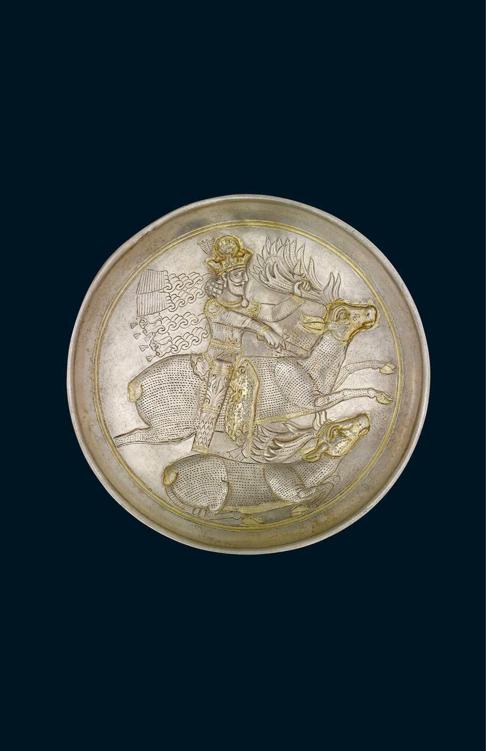

Plate showing Shapur II

AD

309–379

Richard Strauss’s symphonic poem

Thus Spake Zarathustra

is familiar to many people from its use in the soundtrack of the film

2001: A Space Odyssey

.

But few of us know what Zarathustra actually did speak, or even who he was. This is perhaps surprising, because Zarathustra – or, as he is more widely known, Zoroaster – was the founder of one of the great religions of the world. For centuries, along with Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Zoroastrianism was one of the four dominant faiths of the Middle East. It was the oldest of the four – the first of all the text-based religions – and it profoundly influenced the other three. There are still significant Zoroastrian communities all over the world, especially in the religion’s homeland, Iran. Indeed, the Islamic Republic today guarantees reserved seats in its parliament for Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians. In the Iran of 2,000 years ago, Zoroastrianism was the state religion of what was then the Middle Eastern superpower.

The object shown here is a dramatic visualization of power and faith in that Iranian empire. It’s a silver dish from the fourth century, and it shows the king apparently out hunting. In fact, he’s keeping the world safe from chaos.

In Rome at that time Christianity had just become the state religion. Almost contemporaneously, in Iran, the Sasanian Dynasty built a highly centralized state in which secular and religious authority were bound together. At its height this Iranian empire stretched from the Euphrates to the Indus – in modern terms, from Syria to Pakistan. For several centuries it was the equal – and the rival – of Rome in the long struggle to control the Middle East. The Sasanian king shown out hunting on this silver dish is Shapur II, who ruled with resounding success for seventy years, from 309 to 379.

It is a shallow silver dish, about the size and the shape of a small frisbee, made of very high-quality silver, and as you move it around you can see that it has highlights in gold. The king sits confidently astride his mount, and on his head he wears a very large crown with what looks like a winged globe on the top of it. Behind him ribbons flutter over the silver, giving an impression of movement. Everything about his dress is rich – pendant earrings, long-sleeved tunic with carefully embroidered shoulder pads, highly decorated trousers and ribboned shoes. It is an elaborate, carefully worked-out ceremonial image of wealth and power.

You might think that this is pretty predictable: kings have always shown themselves overdressed and dominating animals. But this is much more than a conventional display of prowess and privilege. For the Sasanian kings were not just secular rulers: they were agents of god, and Shapur’s full titles emphasize his religious role: ‘the good worshipper of god, Shapur, the king of Iran and non-Iran, of the divine race of God, the King of Kings’. The god here is of course the god of Zoroastrianism, the religion of the state. The historian Tom Holland tells us about the great prophet and poet Zoroaster:

Zoroaster is the very first prophet in the sense that you would describe Moses or Muhammad as a prophet. No one is entirely sure when, or indeed if, he lived, but if he really did exist then he probably lived in the central Asian steppes in around 1000

BC

. Gradually over the course of the centuries and then the millennia his teachings became the focus for what we could probably call a Zoroastrian church. This increasingly became the state faith of the Iranian people, and therefore of the Sasanian Empire when it was established.The teachings of Zoroaster will sound very familiar to anyone who has been brought up as a Jew, a Christian or a Muslim. Zoroaster was the first prophet to teach that the universe is a battleground between rival forces of good and evil. He was the first to teach that time does not go round in an endless cycle but will come to an end – that there will be an end of days; there will be a day of judgement. All of these notions have passed into the Abrahamic mainstream of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

It is when you come to the animal that the king is riding on the silver dish that you get a shock. He is not on a horse but on a fully antlered stag. He straddles the beast without either stirrups or saddle, gripping it by the antlers with his left hand, while his right hand deftly plunges a sword right into its neck – blood sprays out, and at the bottom of the plate we see the same stag in the throes of death. This whole image is a fantasy, from the great crown at the top, which would quite clearly have fallen off if you’d been riding, to the idea of killing your own mount in full leap.

So what is really going on here? In the Middle East hunting scenes had been a common way of representing royal power for centuries. Assyrian kings, well protected in their chariots, are shown bravely killing lions, from a safe distance. Shapur is doing something else. This is the monarch in single combat with the beast, and he’s risking himself not out of pointless bravado but for the benefit of his subjects. As a protective ruler we see him killing certain kinds of animals, the beasts that threatened his subjects – big cats which preyed on cattle and poultry, wild boar and deer which ravaged crops and pastures. So images like this one are visual metaphors for royal power conceived in Zoroastrian terms. In killing the wild deer the hunter-king is imposing divine order on demonic chaos. Shapur, acting as agent for the supreme Zoroastrian god of goodness, will defeat the forces of primal evil and so fulfil his central role as king.

Guitty Azarpay, Professor of Asian Art at the University of California, Berkeley, highlights the dual role of the king:

It is both a secular image – because of course hunting was enjoyed by most people, by most nations and especially in Iran – and also an expression of the Zoroastrian ideology of the time. Man is God’s weapon against darkness and evil, and he serves the ultimate victory of the cre-ator by following the principle of right measure, leading a life that is prescribed as having good speech, good words and good actions. In this way, the pious Zoroastrian can hope for the best of existence in this life and the best paradise spiritually in the hereafter. The best king is one who as head of state and guardian of religion creates justice and order, is a supreme warrior and a heroic hunter.

This dish is quite clearly meant not just to be seen but to be shown off. It’s an ostentatiously expensive object made from a heavy single piece of silver, and the figures have been hammered out from the back in high relief. The various surface textures have been beautifully rendered by the craftsman, who has chosen different kinds of stippling for the flesh of the animal and the clothing of the king. And the key elements of the scene – the king’s crown and clothing, the heads, tails and hooves of the stags – are highlighted in gold. When this was displayed in the flickering candlelight of a banquet, the gold would have animated the scene and focused attention on the central conflict between the king and the beast. This is how Shapur wanted himself to be seen and his kingdom to be understood. Silver dishes like this one were used by the Sasanian kings in vast quantities, sent as diplomatic gifts across the whole of Asia.

As well as sending silver dishes with symbolic images Shapur also sent Zoroastrian missionaries. It was an identification of the faith with the state that was ultimately to prove very dangerous, especially after the Sasanian Dynasty was swept away and Iran was conquered by the armies of Islam. Tom Holland explains:

Zoroastrianism has really pinned its colours to the Sasanian mast. It has defined itself through the empire and through the monarchy. And so when those collapse, Zoroastrianism is really crippled. Although over time it became accepted that Zoroastrianism should be tolerated, Islam never afforded it the measure of respect that it gave to Christians or to Jews. A further problem was that Christians – even those who had been conquered by Muslims – could look to independent Christian empires, independent Christian kingdoms, and know that there was such a thing as Christendom still in existence. Zoroastrians didn’t have that option – everywhere that had been Zoroastrian had been conquered by Islam. Today, even in the land of its birth, Iran, Zoroastrians are a tiny minority.

But if Zoroastrians today are relatively few in number, some of their faith’s core teachings about the eternal conflict of good and evil, and about the ending of the world, are still very powerful. The politics of the Middle East remain haunted and in some measure shaped by belief in an eventual apocalypse and the triumph of justice – an idea that Judaism, Christianity and Islam all derived from Zoroastrianism. And when politicians in Tehran talk of the Great Satan, and politicians in Washington denounce the Empire of Evil, one is tempted to point out that ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra’.