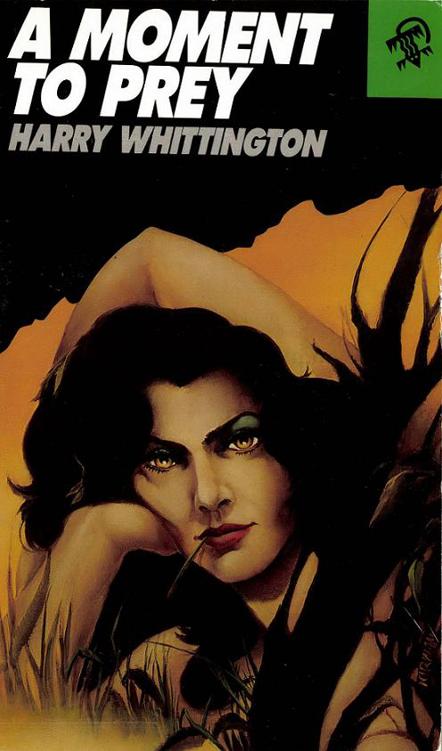

A Moment to Prey

Authors: Harry Whittington

A Moment to Prey

***

Lily knew what she wanted, and that was a man who would take her away from the dirt road and one-room country shack she called home. Lily was different than the other swamp folks, different and smarter. She was looking not only to get out but for something, and it was clear that she'd do anything to get whatever that might be, including commit murder. It was impossible to avoid her, her sleepy eyes that made it seem that she'd just crawled out of a warm bed, her full lips and lush body. An insurance investigator is sent by his company from St. Louis to find out the truth about a hundred thousand dollar scam; he discovers the truth, all right, but Lily makes him concentrate on something altogether different.

Harry Whittington was the king of the paperback originals. He wrote mysteries, westerns, romance and adventure novels. Despite his prolific output, Whittington's work was always of the highest quality. Celebrated and perhaps appreciated most in France, Whittington was lionized by the

Magazine Literaire,

in Paris: "For the past twenty-five years," they wrote, "we in France have considered Harry Whittington one of the masters of the

roman noir

in the second generation-after Hammett, Chandler, Cain."

Magazine Literaire,

in Paris: "For the past twenty-five years," they wrote, "we in France have considered Harry Whittington one of the masters of the

roman noir

in the second generation-after Hammett, Chandler, Cain."

***

"Whittington does some of the best sheer story-telling since the greatest days of the detective pulps."

-Anthony Boucher,

New York Times

"Whittington's writing is crisp, with a good deal of emotional impact."

-Bill Pronzini

***

Bitemeok

(grand book owner & heroic scan provider, OCR) &

P.

(formatting & proofing) edition.

***

I REMEMBER IT WELL

by Harry Whittington

My writing life has been a blast. With all the fallout, fragmentation, frustration and free-falls known to man. I've careened around on heights I never dreamed of, and simmered in pits I wouldn't wish on my worst enemy, and survived. Maybe it's just that I forget quickly and forgive easily.

Looking back, I find it perhaps less than total extravaganza. It all seemed so great at the time: Doing what I wanted to do, living as I wanted to live, having the time of my life and being paid for it. I worked hard; nobody ever wrote and sold 150-odd novels in 20 years without working hard, but I loved what I was doing. I gave my level best on absolutely every piece of my published work, for one simple reason: I knew of no other way to sell what I wrote.

I've known some wonderful people in the writing racket. For some years, I lived in a loose-knit community of real, hard working writers-Day Keene, Gil Brewer, Bill Bran-non, Talmage Powell, Robert Turner, Fred C. Davis. Out in Hollywood, Sid Fleischman and Mauri Grashin are friends, as were Fred C. Fox, Elwood Ullman. And via mail, Frank Gruber, Carl Hodges, Milt Ozaki. Death flailed that company of gallants-Gruber, Fox, Hodges, Ullman, Keene, Gil Brewer, Brannon, Fred Davis-all gone. Talmage Powell's inimitable stories appear in anthologies and magazines and, as of this writing, as I did in the wild and wonderful fifties when we all were young and pretty, I persist.

The fifties. The magic. Tune of change. Crisis. The end of the pulps and the birth of the "original" paperbacks. In recent years critic-writers, Bill Pronzini, Christopher Geist, Michael Barson and Bill Crider have kindly referred to me as "king of the paperback pioneers." I didn't realize at the time I was a pioneer and I certainly didn't set out to be "king" of anything. I needed a fast-reporting, fast-paying market; the paperbacks provided this. I wrote eight, 10, 12 hours a day. Paperback editors bought and paid swiftly. We were good for each other.

***

The reason why I wrote and sold more than almost everybody else was that I was living on the edge of ruin, and I was naive.

James Cagney once said, "It's the naive people who become the true artists. First, they have to be naive enough to believe in themselves. Then, they must be naive enough to keep on trying, using their talent, in spite of any kind of discouragement or doublecross. Pay no attention to setbacks, not even know a setback when it smites. Money doesn't concern them."

Money concerned me. I'd never have dared become a full-time writer if I'd known in the forties that the critically acclaimed "authors" I admired from afar were college professors, ad men, lawyers, reporters, dogcatchers or politicians by day. Fewer than 500 people in the U.S. make their living from full-time free-lance writing. Since 1948, I've been precariously, one of fortune's 500. I persist.

Because, in 1948, I didn't know any better, I quit my government job of 16 years and leaped in, fully clothed, where only fools treaded water. I had a wife, two children and gimlet-eyed creditors standing at my shoulder. I had to write and I had to sell.

At that precise moment, the publishing world was being turned upside down by the Fawcett Publishing Company. When they lost a huge reprint paperback distribution client, they decided to do the unheard of, the insane. They published original novels at 25c a copy. Print order on each title: 250,000. They paid writers not by royalty but on print order. Foreign, movie and TV rights remained with the writer. They were insane. They were my kind of people. Bill Lengel, Dick Carroll and later, Walter Fultz. Elegant men. One hell of a publishing company.

Jim Quinn at HandiBooks; Graphic, Mauri Latzen of Star, and Avon were all swift-remitting markets once the spill-gates broke open. I wrote and they bought. Once Sid Fleischman wrote from Santa Monica: "Just came from the downtown newsstands. My God, Harry, you've taken them over."

It wasn't true. It just seemed true.

***

It wasn't all easy, not all beer and peanuts. There were rough times. You want dues paid?

I came to writing from a love of words. However, I wrote for at least 13 years before I truly learned to plot.

I admired extravagantly Scott Fitzgerald's writings all through the '30s when almost everyone else had forgotten him or, if they remembered, thought he had died, along with prosperity, in 1929. I couldn't afford to buy THE GREAT GATSBY, so I borrowed it over and over from the public library. I haunted used bookstores looking for old magazines in which Fitzgerald might appear.

I met a girl who bought for me-at one hell of an expense in the deepest Depression because they were out of print-all of Fitzgerald's books. I was so overcome with gratitude and joy and exultance that I married her. I still have her, and the books.

I spent at least seven years writing seriously and steadily before I sold anything. June 12, 1943, I sold a short-short story to United Features for $15. In the next couple years I sold them about 25 more 1000-worders, but it was five more years before I sold regularly. In that time, I worked for more than two years with a selfless, patient editor at Doubleday on a book they finally rejected. At this moment, Phoenix Press bought my first western novel, VENGEANCE VALLEY, July 10, 1946.

Using my navy GI bill, I studied writing. Suddenly the scales fell from my eyes. I understood plotting, emotional response, story structure. Fifteen years it took me to learn, but I knew. I could plot-forward, backwards, upside down. It was like being half-asleep and abruptly waking. Never again would I be stumped for plot idea or story line. From the moment I learned to plot, I was assaulted with ideas screaming, scratching and clawing for attention. For the next 20 years I sold everything I wrote. I enjoyed Cadillacs, Canoe cologne, cashmere, Hickey-Freeman jackets and charge accounts you would not believe.

I wrote suspense novels, contemporary romances, westerns, regional "backwoods" tales. People who wonder such things, wondered how I could crossover in these genres with such ease.

All very simple. I could write backwoods sagas because I came from mid-Florida when it was truly Kinnan-Rawlings territory. I could write "cattle-country" fiction because I lived in my teen years on a farm with cows. We had less than a hundred, but when you've known one cow, you've known a thousand. When you've hand-pumped ten-gallon tubs of water from a 100-foot well to fill those bellies, you know more than you need to know. I spent time on horseback, usually without a saddle. When I fell, as I frequently did, unsecured and fast-moving, that wonderful horse stopped in midstride and stood silently until I crawled back aboard. I didn't need to know a thousand horses, I just needed to love that one.

I never wrote westerns about "cowboys" or Indians or "hold-up men." I wrote about people in a raw rugged land who loved, hated, feared and saw murder for what it was- murder. They got sick at the thought of using a gun. They used guns as you would in the same situation-as a last resort.

There was much talk in the fifties about the writers who "lived" their suspense stories. I didn't write that kind of suspense story anyway. I wrote about

people,

their insides, their desires, and fears and hurts and joys of achievement and loss. I wrote about love which flared white hot and persisted against all odds, because I was fool enough then to believe- and I still believe-that true love does persist, does not alter when it alteration finds. It may buckle in the middle sometimes, but it does not bend with the remover to remove.

people,

their insides, their desires, and fears and hurts and joys of achievement and loss. I wrote about love which flared white hot and persisted against all odds, because I was fool enough then to believe- and I still believe-that true love does persist, does not alter when it alteration finds. It may buckle in the middle sometimes, but it does not bend with the remover to remove.

If a character hurt in his guts, I wrote to make you

feel

how bad he hurt. I knew about emotional pain, which is the worst kind, and about physical pain. I was in two fights. In one, I got my front teeth smashed loose. In the other, overmatched, I was struck sharply in each temple by fists with third knuckle raised like a knot. When I wrote about pain, I knew what I was talking about. You don't have to die in a fire to write truly about arson.

feel

how bad he hurt. I knew about emotional pain, which is the worst kind, and about physical pain. I was in two fights. In one, I got my front teeth smashed loose. In the other, overmatched, I was struck sharply in each temple by fists with third knuckle raised like a knot. When I wrote about pain, I knew what I was talking about. You don't have to die in a fire to write truly about arson.

How I came to write suspense stories is something else. Bill Brannon, in Chicago, said he could sell all the suspense novelettes-about 10,000 words each-I could write.

***

Since I wanted only to be Scott Fitzgerald, with a touch of sardonic Maugham and J.P. McEvoy humor, I told Bill I hated suspense stories, never read them, and certainly couldn't write them. But I was in Chicago attending a writers' conference when I said that.

Having no idea what hellish jokes fate had stored up for me, I caught the bus home from Chicago-36 hours of leaving the driving to them. I was hemmed in against a window by a lady who looked like a giant-economy sized Nell Carter. In an attempt to escape, my mind plotted out the first suspense story I'd ever attempted. I got home on a Monday, wrote the story that night and mailed it the next day to Bill. That Friday I got a check from King Features Syndicate for $250. For at least 20 years I got small royalty checks from King Features on the 30 novelettes I did for them starting in 1949.

My path had been chosen for me. Fredric Pohl, who was an agent then, sold my first western novelette to Mammoth Western, "Find This Man With Bullets." Bill Brannon sold my suspense novel, SLAY RIDE FOR A LADY to Jim Quinn at Handibooks. I was on my way. I was less than a household name, but I was too busy, and having too much fun, to care. The people who read my books said I was a good writer, a damned good writer. How could I argue with that?

The New York Times, July 18, 1954: "Whittington does the best sheer story telling since the greatest pre-sex days of the detective pulps… YOU'LL DIE NEXT is a very short novel, which is just as well. I couldn't have held my breath any longer in this vigorous pursuit tale whose

plot

is too dexteriously twisted even to mention in a review."

plot

is too dexteriously twisted even to mention in a review."

Baby, I could

plot!

plot!

From

Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine

(Paris Edition) 1958: "MAN IN THE SHADOW-Whittington's style is uncommonly lean and bare-it must have been difficult for the adapter to get his tone for French readers. But the impact is vigorous, the craftsmanship so smooth that one identifies with these characters, in their anxieties, their furies, their indignation, their rebelling against injustice, so we fully recommend this book to you."

Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine

(Paris Edition) 1958: "MAN IN THE SHADOW-Whittington's style is uncommonly lean and bare-it must have been difficult for the adapter to get his tone for French readers. But the impact is vigorous, the craftsmanship so smooth that one identifies with these characters, in their anxieties, their furies, their indignation, their rebelling against injustice, so we fully recommend this book to you."

And

Le Monde,

the largest newspaper of Paris, 1957: "With this novel, FRENZIE PASTORALE

(Desire in the Dust),

which compares favorably with Erskine Caldwell's best, Whittington asserts himself as one of the greats among American novelists." You can imagine how I blushed.

Le Monde,

the largest newspaper of Paris, 1957: "With this novel, FRENZIE PASTORALE

(Desire in the Dust),

which compares favorably with Erskine Caldwell's best, Whittington asserts himself as one of the greats among American novelists." You can imagine how I blushed.

Nov. 4, 1955, the New York

Times:

"In THE HUMMING BOX, Whittington once again proves himself one of the most versatile and satisfactory creators of contemporary fiction-tightly told, recalling the best of early James M. Cain."

Times:

"In THE HUMMING BOX, Whittington once again proves himself one of the most versatile and satisfactory creators of contemporary fiction-tightly told, recalling the best of early James M. Cain."

Other books

Texas Wildfire (Texas Heroes Book 1) by Sable Hunter

The Pursuit of Tamsen Littlejohn by Lori Benton

Incarnadine by Mary Szybist

Amanda Scott - [Border Trilogy Two 02] by Border Lass

Night Birds On Nantucket by Joan Aiken

Once Was Lost by Sara Zarr

SM 101: A Realistic Introduction by Jay Wiseman

Ice Time by David Skuy

Best Kept Secret by Amy Hatvany

Claimed by Rebecca Zanetti