A People's Tragedy (41 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

eventual act of abdication in 1917 — which he said he had signed so as not to be forced to relinquish his coronation oath to uphold the principles of autocracy — was such a bitter pill to him. Witte later claimed that the court set out to use his Manifesto as a temporary concession and that it had always intended to return to its old autocratic ways once the danger passed.56 He was almost certainly correct. By the spring of 1906 the Tsar was already going back on the promises he made the previous October, claiming that the Manifesto had not in fact placed any limits on his own autocratic prerogatives, only on the bureaucracy.

The Manifesto's proclamation was met with jubilation in the streets. Despite the rainy weather, huge numbers of people converged in front of the Winter Palace with a large red flag bearing the inscription 'Freedom of Assembly'. As they must have been aware, they had at last managed to do what their fellow subjects had failed to do on 9 January.

Bloody Sunday had not been in vain, after all. In Moscow 50,000 people gathered in front of the Bolshoi Theatre. Officers and society ladies wore red armbands and sang the Marseillaise in solidarity with the workers and students. The general strike was called off, a partial political amnesty was proclaimed, and there was a euphoric sense that Russia was now entering a new era of Western constitutionalism The whole country, in the words of one liberal, 'buzzed like a huge garden full of bees on a hot summer's day'57 The newspapers were filled with daring editorials and hideous caricatures of the country's rulers, as the old censorship laws ceased to function. There was a sudden boom in pornography, as the limits of the new laws were tested. In Kiev, Warsaw and other capitals of the Empire, a flood of new publications appeared in the language of the local population as Russification policies were suspended. Political meetings were held in the streets, in squares and in parks, in all public places, as people no longer feared arrest. A new and foreign-sounding word was now invented —

mitingovanie

— to describe the craze for meetings displayed by these newborn citizens.

Nevsky Prospekt became a sort of Speakers' Corner, a people's parliament on the street, where orators would stand on barrels, or cling to lamp-posts, and huge crowds would instantly gather to listen to them and grab the leaflets which they handed out. Socialist leaders returned from exile. New political parties were formed. People talked of a new Russia being born. These were the first heady days of freedom.

iii A Parting of Ways

It was in October 1905 that Prince Lvov, the liberal zemstvo man', enrolled as a member of the Kadets. The decision had not been an easy one for him to make, for Lvov, by nature, was not a 'party man'. His political outlook was

essentially practical — that is what had drawn him into zemstvo affairs — and he could not easily confine himself to the political dogma of any one party. His knowledge of party politics was almost non-existent. He regularly confused the SDs with the SRs and, according to his friends, did not even know the main points of the Kadet programme. 'In all my years of acquaintance with Prince Lvov', recalled V A. Obolensky, 'I never once heard him discuss an abstract theoretical point.' The Prince was a 'sceptical Kadet', as Miliukov, the party's leader, once put it. He was always on the edge of the party's platform and rarely took part in its debates. Yet his opinions were eagerly sought by the Kadet party leaders and he himself was frequently called on to act as a mediator between them. (It was his practical common sense, his experience of local politics, and his detachment from factional squabbles, that would eventually make Lvov the favoured candidate to become the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government in March I9I7.)58

Of all the political parties which sprang up in the wake of the October Manifesto, the Constitutional Democrats, or Kadets for short, was the obvious one for Lvov to join. It was full of liberal zemstvo men who, like him, had come to the party through the Liberation Movement. The agenda of the movement was in the forefront of the Kadet party programme passed at its founding congress in October 1905. The manifesto concentrated almost exclusively on political reforms — a legislative parliament elected on the basis of universal suffrage, guarantees of civil rights, the democratization of local government, and more autonomy for Poland and Finland — not least because the left and right wings of the party were so divided on social issues, the land question above all. But perhaps this concentration was to be expected in a party so dominated by the professional intelligentsia, a party of professors, academics, lawyers, writers, journalists, teachers, doctors, officials and liberal zemstvo men. Of its estimated 100,000 members, nobles made up at least 60 per cent. Its central committee was a veritable 'faculty' of scholars: 21 of its 47 members were university professors, including its chairman, Pavel Miliukov (1859—1943), who was the outstanding historian of his day. These were the 'men of the eighties' — all now in their forties.

They had a strong sense of public duty and Western-liberal values, but very little idea of mass politics. In the true tradition of the nineteenth-century intelligentsia they liked to think of themselves as the leaders of 'the people', standing above narrow party or class interests, yet they themselves made very little effort to win the people over to their cause.59 For in their hearts, as in their dinner-party conversations, they were both afraid and contemptuous of the masses.

Among the other liberal groups to emerge at this time, the most important was the Octobrist Party. It took its name from the October Manifesto of 1905, which it saw as the basis for an era of compromise and co-operation

between the government and public forces and the creation of a new legal order. It attracted some 20,000 members, most of them landowners, businessmen and officials of one sort or another, who favoured moderate political reforms but opposed universal suffrage as a challenge to the monarchy, not to mention to their own positions in central and local government.60 If the Kadets were liberal-radicals', in the sense that they kept at least one foot in the democratic opposition, the Octobrists were 'conservative-liberals', in the sense that they were prepared to work for reform only within the existing order and only in order to strengthen it.

Lvov himself might have been tempted to join the Octobrists, for D. N. Shipov, his old political mentor and friend from the national zemstvo movement was one of the party's principal founders, while Alexander Guchkov, a comrade-in-arms from the relief campaign in Manchuria, became its leader. But the bitter reform struggle of the previous ten years had taught him not to trust so blindly in the willingness of the Tsar to deliver the promises he had made in his Manifesto. The Prince preferred to remain with the Kadets in a stance of scepticism and half-opposition to the government, rather than join the Octobrists in declarations of loyal support.

This was, in truth, the main dilemma that the liberals faced after the October Manifesto

— whether to support or oppose the government. So far the revolution had been a broad assault by the whole nation united against the autocracy. But now the Manifesto held out the prospect of a new constitutional order in which both monarchy and society might — just might — develop along European lines. The situation was delicately balanced. There was always the danger that the Tsar might renege on his constitutional promises, or that the masses might become impatient with the gradual process of political reform and look instead to a violent social revolution. Much would depend on the role of the liberals, who had so far led the opposition movement and who were now strategically placed between the rulers and the ruled. Their task was bound to be difficult, for they had to appear both moderate (so as not to alarm the former) and at the same time radical (so as not to alienate the latter).

Witte, who was charged with forming the first cabinet government in October, offered several portfolios to the liberals. Shipov was offered the Ministry of Agriculture, Guchkov the Ministry of Trade and Industry, the liberal jurist A. F. Koni was selected for the Ministry of Justice, and E. N. Trubetskoi for Education. Prince Urusov, whom we encountered as the Governor of Bessarabia (see pages 42—5), and who sympathized with the Kadets, was considered for the all-important post of Minister of the Interior (although he was soon rejected on the grounds that, while 'decent' and even 'fairly intelligent', he 'was not a commanding personality'). Two other Kadets, Miliukov and

Lvov, were also offered ministerial posts. But not one of these 'public men' agreed to join Witte's

EVERYDAY LIFE UNDER THE TSARS

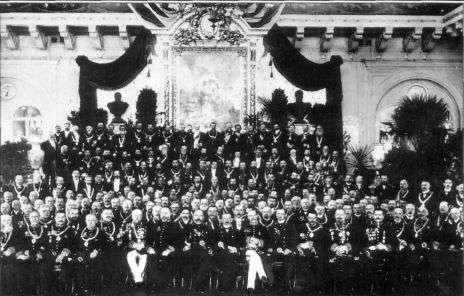

14 The city mayors of Russia in St Petersburg for the tercentenary in 1913.

15 The upholders of the patriarchal order in the countryside: a group of volost elders in 1912.

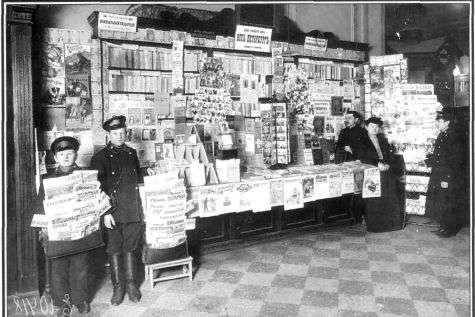

16 A newspaper kiosk in St Petersburg, 1910. There was a boom in newspapers and pamphlets as literacy expanded and censorship was relaxed following the 1905

Revolution.

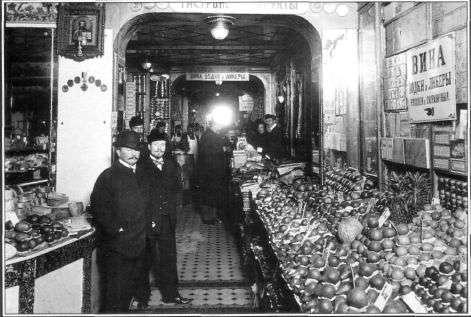

17 A grocery store in St Petersburg, circa 1900. Note the icon in the top-left corner, a sign of the omnipresence of the Church.