A People's Tragedy (42 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

18-19 A society of extreme rich and poor.

Above:

dinner at a ball given by Countess Shuvalov in her splendid palace on the Fontanka Canal in St Petersburg at the beginning of 1914.

Below:

a soup kitchen for the unemployed in pre-war St Petersburg.

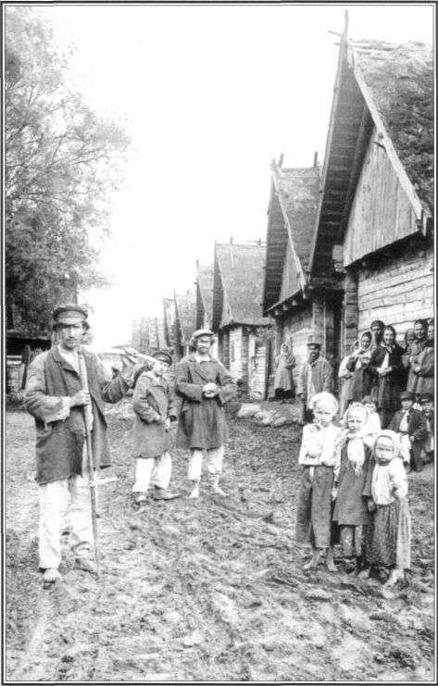

20 Peasants of a northern Russian village, mid-1890s. Note the lack of shoes and the uniformity of their clothing and their houses.

21-2 Peasant women were expected to do heavy labour in addition to their domestic duties.

Above:

a peasant's two daughters help him thresh the wheat.

Below,

peasant women haul a barge on the Sura River under the eye of a labour contractor.

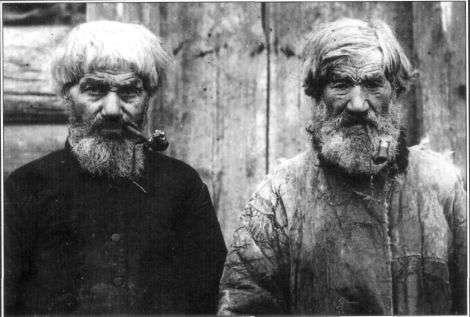

23 Serfdom was still within living memory. Twin brothers, former serfs, from Chernigov province, 1914.

24 A typical Russian peasant household - two brothers, one widowed, each with four children - from the Volokolamsk district, circa 1910.

25 A meeting of village elders, 1910. Most village meetings were less orderly than this.

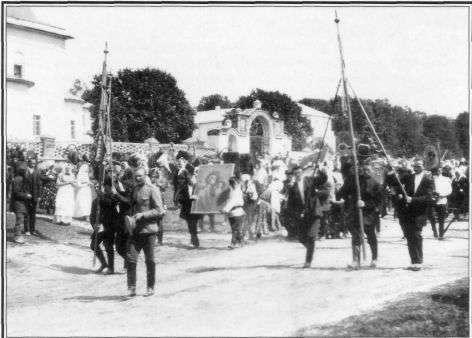

26 A religious procession in Smolensk province. Not all the peasants were equally devoted to the Orthodox Church.

27 The living space of four Moscow workers in the Sukon-Butikovy factory dormitory before 1917.

28 Inside a Moscow engineering works, circa 1910.

government, which in the end had to be made up of tsarist bureaucrats and appointees lacking public confidence.61

It is a commonplace that by their refusal to join Witte's cabinet the liberals threw away their best chance to steer the tsarist regime towards constitutional reform. But this is unfair. The ostensible reason for the breakdown of negotiations was the liberals' refusal to work with P. N. Durnovo, a man of known rightist views and a scandalous past,*

who had, it seems, been promised the post of Minister of the Interior, and who was now suddenly offered it in preference to Urusov. But the Kadets were also doubtful that Witte would be able to deliver on the promises of the October Manifesto in view of the Tsar's hostility to reform. They were afraid of compromising themselves by joining a government which might be powerless against the autocracy. Their fears were partly conditioned by their own habitual mistrust of the government and their natural predilection towards opposition. 'No enemies on the Left' — that had been their rallying cry during the struggles of 1904—5. And the triumph of October had only confirmed their commitment to the policy of mass agitation from below. Their doubts were hardly groundless. Witte himself had expressed the fear that the court might be using him as a temporary expedient, and this had come out in his conversations with the Kadets. On one occasion Miliukov had asked him point blank why he would not commit himself to a constitution: Witte had been forced to admit that he could not 'because the Tsar does not wish it'.62 Since the Premier could not guarantee that the Manifesto would be carried out, it was not unreasonable for the liberals to conclude that their energies might be better spent in opposition rather than in fruitless collaboration with the government.

In any case, it soon became clear that the 'liberal moment' would be very brief. Only hours after the declaration of the October Manifesto there was renewed fighting on the streets as the country became polarized between Left and Right. This violence was in many ways a foretaste of the conflicts of 1917. It showed that social divisions were already far too deep for a merely liberal settlement. On 18 October, the day the Manifesto was proclaimed, some of the jubilant Moscow crowds resolved to march on the city's main jail, the Butyrka, to demonstrate for the immediate release of all political prisoners. The protest passed off peacefully and 140 prisoners were released. But on their way back to the city centre the demonstrators were attacked by a large and well-armed mob carrying national flags and a portrait of the Tsar. There was a similar clash

* In 1893, when he was working in the Department of Police, Durnovo had ordered his agents to steal the Spanish Ambassador's correspondence with his prostitute mistress, with whom Durnovo was also in love. The Ambassador complained to Alexander III, who ordered Durnovo's immediate dismissal. But after Alexander's death he somehow managed to revive his career.

outside the Taganka jail, where one of the prisoners who had just been released, the Bolshevik activist N. E. Bauman, was beaten to death.

For the extreme Rightists this was to be the start of a street war against the revolutionaries. Several Rightist groups had been established since the start of 1905.

There was the Russian Monarchist Party, established by V A. Gringmut, the reactionary editor of

Moscow News,

in February, which called for the restoration of a strong autocracy, martial law, dictatorship and the suppression of the Jews, who, it was claimed, were mainly the 'instigators' of all the disorders. Then there was the Russian Assembly, led by Prince Golitsyn and made up mainly of right-wing Civil Servants and officers in St Petersburg, which opposed the introduction of Western parliamentary institutions, and espoused the old formula of Autocracy, Orthodoxy and Nationality.

But by far the most important was the Union of the Russian People, which was established in October by two minor government officials, A. I. Dubrovin and V M.

Purishkevich, as a movement to mobilize the masses against the forces of the Left. It was an early Russian version of the Fascist movement. Anti-liberal, anti-socialist and above all anti-Semitic, it spoke of the restoration of the popular autocracy which it believed had existed before Russia was taken over by the Jews and intellectuals. The Tsar and his supporters at the court, who shared this fantasy, patronized the Union, as did several leading Churchmen, including Father John of Kronstadt, a close friend of the royal family, Bishop Hermogen and the monk Iliodor. Nicholas himself wore the Union's badge and wished its leaders 'total success' in their efforts to unify the 'loyal Russians' behind the autocracy. Acting on the Tsar's instructions, the Ministry of the Interior financed its newspapers and secretly channelled arms to it. The Union itself was appalled, however, by what it saw as the Tsar's own weakness and his feeble failure to suppress the Left. It resolved to do this for him by forming paramilitary groups and confronting the revolutionaries in the street. The Black Hundreds,* as the democrats called them, marched with patriotic banners, icons, crosses and portraits of the Tsar, knives and knuckle-dusters in their pockets. By the end of 1906 there were 1,000