A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (6 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

As long as you keep the arrangement of whole-steps and half-steps the same, you can build a major scale by starting on any note in the chromatic scale. The note on which the scale starts is called the tonic, because it provides a reference point for the tonality of the music. Another term for the same concept is key. When the major scale starts and ends on the note D, for example, we say that it's in the key of D, and that D is the tonic.

Figure 1-10. The pattern of whole-steps and half-steps in the C major scale.

In addition to their letter-names, the notes in the major scale have another set of names, which are also shown in Figure 1-11 - do, re, mi, fa, so, la, and ti. (In Europe, "do" is also known as "ut," and "ti" is sometimes called "si" "Sol" is an alternative for "so," but because it's followed by "la," the final "1" sometimes gets dropped.) Many young music students learn these nonsense syllables in grade school. The syllables have one advantage over the letter-names for the notes: Do, re, mi, and the other names are the same no matter what note the scale starts on.

KEY SIGNATURES & ACCIDENTALS

Since the major scale is used in so much of our music, and since our tuning system so conveniently allows us to start a major scale on any note of the chromatic scale, music is often full of notes that are played on the black keys of the keyboard. Maybe you can imagine how messy it would be if, each time we encountered an A in sheet music, the sheet music had to indicate whether we were to play an A6 (the black key below A), an A# (the black key above A), or an An (the white key). To make music easier to read, this information is placed not within each measure but at the beginning of each staff.

Figure 1-11. The notes of the major scale have nonsense names. (In Europe, "do" is often referred to as "ut " and "so" is "sol"). These names are the same no matter what key the music is in; they're shown here with a C major scale purely for convenience. "Do" always refers to the tonic, "re" to the 2nd step of the scale, and so on.

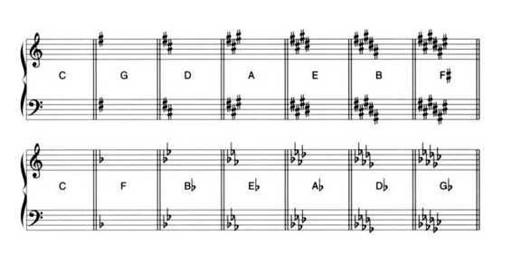

Figure 1-12. The key signatures of the major keys. The flats or sharps placed at the beginning of the staff (or after a double bar line, as shown here) indicate which notes on the staff are to be played a half-step higher or lower than the white key that would otherwise be played. In the key of D, for instance, all of the occurrences of the note F in the staff would be played as F#, and all of the occurrences of C would be played as C#.

In sheet music, whenever the music is in a key other than C, a key signature (a group of one or more sharps or flats) is found at the beginning of each staff. The key signature tells you which notes to raise or lower by a half-step in order to produce a major scale. It's placed at the beginning of each staff, and applies to all of the notes of that pitch class that are found anywhere in the staff, whether or not they're in the same octave as the accidental in the key signature. The basic key signatures are shown in Figure 1-12, and Figure 1-13 shows how to interpret a key signature.

Figure 1-13. The key signature with three flats indicates that the music is in the key of E6 major - or possibly in the relative minor of E6 major, which is C minor. Relative minor keys are discussed in Chapter Four. When this key signature is used, an E6 major scale can be written using no accidentals, as in (a). When no key signature is used (b), the same scale has to be written using an accidental before the first occurrence of any E6, A6, or B6 in any measure.

There are a few pieces of modern music whose key signatures include both flats and sharps, but we can safely ignore these. Note also that in some sheet music prepared by arrangers for recording sessions, the key signature is shown not at the beginning of each staff but only at the beginning of the piece. The assumption is that the people reading the sheet music will be professionals, and will be able to remember what key they're playing in.

Whenever the composer or arranger needs to temporarily cancel one of the flats or sharps in the key signature, an accidental (a flat, sharp, or natural, or more rarely a double-sharp or double-flat) is placed before the note that is to be altered. Looking at it a slightly different way, an accidental is not the flat, sharp, or natural in the sheet music but rather a note that isn't included in the major scale indicated by the current key signature. In the key of E6, for example, an An (a white key) would be an accidental.

Each key signature is referred to by the name of the tonic note of the major scale that can be played using that key signature without inserting any accidentals. For instance, if the key signature allows us to play a D major scale with no accidentals - that is, if it contains exactly two sharps - it's the D major key signature.

In symphonic music, the key signature may change a number of times in the course of a single piece. This happens when the music modulates to a new key (a subject we'll have more to say about in Chapter Eight). Composers change the key signature in order to make a passage easier for the musicians to read. It's easier to read because fewer accidentals are required to notate it. On the down side, it becomes necessary to make a mental note of the current key signature at all times.

MAJOR KEYS, SCALES & THE CIRCLE OF FIFTHS

Because there are 12 notes in the chromatic scale, it's possible to play a major scale in any of 12 different keys. For reference, Figure 1-14 shows all 12 of these scales. Assuming you know how to read music, you may be more used to seeing the scales written with key signatures. In Figure 1-14, however, I've notated them without key signatures, using accidentals, as this makes it easier to see how various notes are raised or lowered.

The arrangement of keys in Figures 1-12 and 1-14 is not random or capricious: The scales are arranged in an order called the Circle of Fifths. The Circle of Fifths is so important that it deserves a brief explanation here. We'll have more to say about it in Chapter Five.

Studying Figures 1-12 and 1-14 is a worthwhile exercise. As you examine them, you'll notice some patterns. When we add a sharp or remove a flat, for instance, the note that's affected is the note just below the tonic. As we transition from the key of A to the key of E, for instance, the note D (one step below E) changes to a D#. See if you can figure out which note of the scale is lowered by a half-step when the key signature moves the other direction, for example from the key of C to the key of F, or from F to B6. (Note also that these Figures show only the major keys. The subject of minor keys will have to wait until Chapter Four.)

Figure 1-14. The major scales, written without key signatures. If the key signatures shown in Figure 1-12 were used, the scales here would look a lot alike: They'd all be simple rows of notes, with no accidentals. Note that the scales of F# major and G6 major contain exactly the same chromatic pitches. However, each pitch is spelled using one of two enharmonic equivalents: F# is the same note as G6, G# is the same as A6, and so on.

When a piece of music originally written in one key is moved up or down in pitch so that it's in a different key, we say that the music has been transposed. Transposing music to a new key is often necessary so that a vocalist can sing the melody without straining.

Transposition doesn't mean simply slapping a new key signature on an existing bunch of notes. If we did that, the melody and harmony would most likely sound very strange. Instead, all of the notes are moved up or down by some number of half-steps so that the tonic note (for example, G in the key of G major) lands on the tonic of the new key (for example, E6 in the key of E6). All of the other notes in the piece are moved up or down by the same number of half-steps, with the result that the music sounds exactly the way it did before, only higher or lower.

ENHARMONIC EQUIVALENTS

Look again at Figure 1-14. If you play the F# and G6 scales on a keyboard (or, for that matter, on a guitar or any other instrument) you'll find that you're using exactly the same notes, even though the two scales look completely different on the page. In fact, this is an extreme instance of a more general phenomenon: Many other notes found in two different scales are spelled differently while sounding the same - for instance, the D# in the B major scale is the same note as the E6 in the B6 major scale. What's unique about the scales of F# and G6 is that all of the notes are the same, but spelled differently.

Notes that sound and are played the same, but are spelled differently, are called enharmonic equivalents. The word "spell" in this case refers simply to the choice of which letter we use to refer to the note. As we move into more advanced harmonic territory, we'll encounter many enharmonic equivalents.

The fact that a given note can be spelled two different ways may seem at first to be merely an inconvenience. Why can't we always call a given note by a single name, and be done with it? (In fact, I've met a few guitarists who do exactly this. To them, the note a half-step above C is always D6, never C#.) There's an important reason for it, however. When notating scales, we want the scale to look sensible on the page, with one scale step per line or space on the staff. For instance, in the A scale, the notes A, B, C#, and D follow one another in a neat line. If we were to spell the third note as D6, then the A scale would contain the notes A, B, D6, and D. There would be two D's in the scale, and no C. This would make reading sheet music quite difficult. What would we use for a key signature? Would we put a flat on the line for the D, or not?