A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (10 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

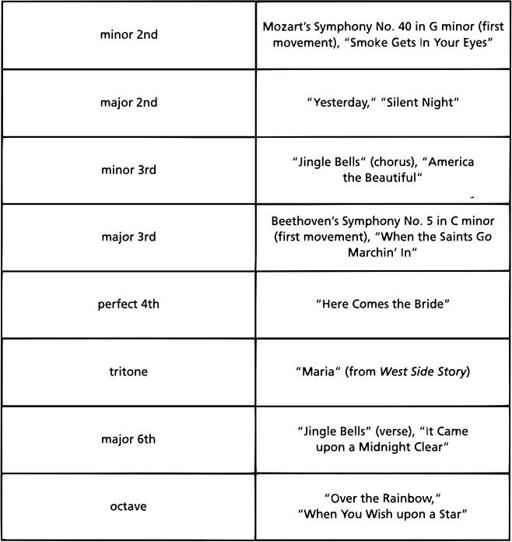

You may be able to think of other songs besides the ones listed. Note that some of these tunes use the ascending version of the interval (the lower note before the upper one), while others use the descending version (upper note first).

Quiz

1. What is the name of the interval created by removing one half-step from a perfect 4th? Give two answers - one for the interval in which the letter-names of the two notes have not changed, and another for the interval in which one of the two notes has a new letter-name.

2. When two intervals can be stacked to form a perfect octave, what is their relationship called?

3. If a minor 2nd is increased by an octave, what interval results?

4. How many half-steps are there in a diminished 7th? In a diminished 3rd?

5. Give three different names for the interval that contains six half-steps.

6. Explain why there's no such interval as a perfect 3rd, and no such interval as a minor 5th.

7. Which is larger - a major interval or a minor interval? (Assume that each is spelled with the same two letter-names, so that each has the same number of scale steps.)

8. What note is a major 6th above A? A minor 3rd below G? A diminished 5th below B?

9. What interval is the inversion of a major 3rd? Of a minor 2nd? Of an augmented 4th?

10. What is the name of the interval between the D below Middle C and the D# above Middle C?

3

TRIADS

ith some exceptions in the area of contemporary classical music, all harmonic activity in conventional European/American music is based on the triad. As its name implies, a triad is a set of three notes. Not just any three notes will do, however. The notes in a triad have specific relationships to one another. (In Chapter Six we'll look at a few three-note chords that are not triads.)

ith some exceptions in the area of contemporary classical music, all harmonic activity in conventional European/American music is based on the triad. As its name implies, a triad is a set of three notes. Not just any three notes will do, however. The notes in a triad have specific relationships to one another. (In Chapter Six we'll look at a few three-note chords that are not triads.)

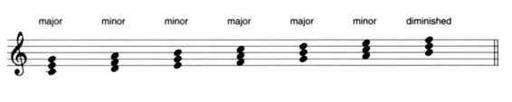

A triad is built by stacking two 3rds. As Figure 3-1 shows, there are four ways to do this. We can put a major 3rd on the bottom and a minor 3rd on the top, reverse the order and put a minor 3rd on the bottom and a major 3rd on the top, or combine either two major 3rds or two minor 3rds.

These four triads have names. The first two, which are used somewhat more often, are named after the lower of the 3rds: The triad in which the major 3rd is on the bottom and the minor 3rd on top is referred to as a major triad. When the minor 3rd is on the bottom and the major 3rd on top, the triad is a minor triad. The other two types are named after the type of 5th that lies between the bottom and top notes: The triad built out of two major 3rds is called an augmented triad, because its outer two notes form an augmented 5th, and the triad built of two minor 3rds is called a diminished triad, because its outer two notes form a diminished 5th.

Figure 3-1. Triads are created by stacking pairs of 3rds. Since each 3rd can be either major or minor, there are four possible triads.

Figure 3-2. The names of the notes within a triad.

Each of the notes in a triad has a name, as shown in Figure 3-2. The bottom note is called the root, because it's the foundation on which the rest of the triad is built. The middle note is called the 3rd, because the interval between it and the root is a 3rd. The top note is called the 5th, again because the interval between it and the root is a 5th. When we study more complex chords, you'll find that this naming convention is used consistently: Each note in a chord is named after the interval created by its relationship with the root. But as mentioned in Chapter Two, it's important to understand that at this point we're using the terms "3rd" and "5th" in two distinct ways. Any two notes that are the right distance apart form an interval of a 3rd - but the upper note of the interval isn't necessarily the 3rd of the triad in which the two notes are being played. Looking at Figure 3-1, for instance, we can see that the interval of a 3rd separates the E and G in a C major triad. But that doesn't make the G the 3rd of the triad. The G is the 5th of the C major triad, because it's a 5th above the root. (G is also the 3rd of a different triad, one whose root is E.)

THE DIATONIC TRIADS IN THE MAJOR SCALE

In Chapter Two we looked at all of the intervals that are found in the major scale. We can construct whole triads out of the same scale, as Figure 3-3 shows. Play this example on the keyboard in order to get its sound firmly in your ear. You'll note that major triads are formed on the tonal steps of the scale (the tonic, 4th, and 5th), while the triads built on the modal steps are minor or diminished. There are no augmented triads within the major scale.

These triads are called diatonic because they use only the notes of the major scale, with no accidentals. If there were any accidentals in Figure 3-3, we'd have to say that some of the triads were chromatically altered. For comparison, play the triads in Figure 3-4. The roots of the triads in this figure are all within the major scale, but all of the triads are major.

Figure 3-3. The diatonic triads in C major.

The only diminished diatonic triad is the one built on the 7th step of the scale. While the other diatonic triads are often used in unaltered form in musical compositions, this diminished triad is rarely used by itself. As you'll learn in the next chapter, however, it's an important part of a more advanced type of chord called a dominant 7th chord.

Figure 3-4. In order to build a major triad on each step of the C major scale, we have to add accidentals. The first and last chords in each measure are diatonic, because all of their notes are drawn from the C major scale. However, the second and third chords in each measure are chromatically altered: They contain one or more notes that are not part of the C major scale.

CHORD NAMES OF TRIADS

Look again at Figure 3-3, and identify the root of each triad. (It's the bottom note in the triad.) The chord name of a triad consists of the letter-name of the root followed by a description of the type of triad. The root of the first triad is C, and it's a major triad, so it's called a C major chord. The root of the second triad is D, and it's a minor triad, so it's a D minor chord. And so on.

In the case of triadic chords - chords that consist of triad notes with no other notes - the word "chord" is often used in place of "triad:" If someone refers to a G major chord, for instance, without giving any further description, you can safely assume that they're referring to a triad, a chord containing only the notes G, B, and D.

With this extremely practical bit of knowledge at your fingertips, you'll be able to pick out accompaniments for dozens of well-known songs. Any song that uses only simple triads can be harmonized (that is, a harmony part can be added) by playing the appropriate triads beneath the melody. On the keyboard, the usual way to do this is by playing the chords with the left hand and the melody with the right. On the guitar, you'd be more likely to play the chords while singing the melody, though guitar arrangements in which the melody is played on the upper strings while the harmony is filled in on the lower strings are very common. Most guitarists don't play simple triads, however. Chords played on guitar are typically rearranged in various ways. The methods used for rearranging the notes of triads are discussed in the remainder of this chapter, and you'll find some basic information on guitar chord voicings in Appendix B.