A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (11 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

In published sheet music, the names of the chords (which might be either simple triads or other chord types) are often placed above or below the melody. Three examples are shown in Figure 3-5. This type of music is called a lead sheet, because it contains the lead part (the melody) and is usually printed on a single sheet of paper. In performing the songs in Figure 3-5 on the keyboard, you might play something like the music in Figure 3-6. The left-hand parts in Figure 3-6 show the simplest possible interpretations of the chord symbols in Figure 3-5.

Figure 3-5. Three classic melodies in lead sheet form. The chords to be used for accompaniment are shown. Each chord should be used starting on the beat where the symbol is placed, and should continue until the point in the music where the next chord symbol appears.

The rules for interpreting chord symbols can get a little convoluted, as we'll see in Chapters Five and Six. Fortunately, the basics are unambiguous and easy to remember. When you see a letter-name with no other symbols, play a major chord (one containing only the notes in the major triad). When you see a lettername followed by the letter "m," play a minor chord (triad). The abbreviations "aug" and "dim" are used for augmented and diminished chords respectively. Some arrangers use a plus sign (+) in place of "aug," a minus sign (-) to indicate a minor chord, and a small raised circle (0) to indicate a diminished chord.

Figure 3-6. A simple way of performing the songs shown in Figure 3-5. The left-hand parts shown are realizations of the chord symbols in Figure 3-5. Note that some chords are repeated in order to provide a steady rhythm, even though the lead sheet melodies don't show a repetition of the chord symbol. Many of the notes in the melodies are also found in the triads, but a few are not. These non-chord notes are discussed in Chapter Seven, in the section "Non-Chord Tones. "

If you see any chord symbols on the lead sheet other than the letter-name and the abbreviation "m," "aug," or "dim" (or equivalent symbols), the chord has other notes in it besides the notes in the basic triad. Such chords are discussed in Chapters Five and Six.

INVERSIONS OF TRIADS

The left-hand accompaniment parts in Figure 3-6 look and sound quite stiff, because the chords have been played in the most basic possible way. In order to loosen up the accompaniment, we need to explore some ways to change the chord voicings. A voicing is simply a way of arranging or rearranging the notes in the chord. Any combination of notes that includes only notes found within a given chord is a voicing of that chord.

The easiest way to change a basic triadic voicing is to move the bottom note up an octave or the top note down an octave. Doing this produces an inversion. Inverting a chord is very much like inverting an interval (see Chapter Two). The main difference is that when an interval is inverted, its name changes: An inverted major 3rd becomes a minor 6th, for example. When a chord is inverted, however, its name remains the same. Also, there are three notes in a triad rather than two, so we have more possible inversions.

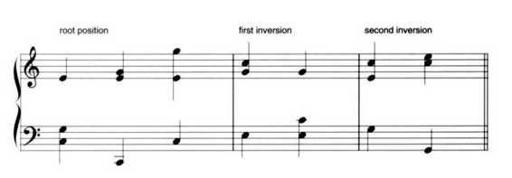

When the root of the triad is on the bottom, we say that the triad is in root position. When the root is moved up an octave so that the lowest note is the 3rd of the triad, the triad is in first inversion. When the 3rd is also moved up, so that the 5th is the lowest note, the triad is in second inversion. Figure 3-7 shows these voicings.

When an augmented triad is inverted, something odd and interesting happens: It's not possible to tell that it's inverted by listening to it. For instance, if we invert a Caug triad, as shown in Figure 3-8, we get something that sounds exactly like an Eaug triad. This happens because each major 3rd in an augmented triad is four half-steps wide. There are 12 half-steps in the octave, and 12 divided by four is exactly three, so the augmented triad divides the octave into three equal intervals, each consisting of four half-steps.

Figure 3-7. A C major chord in root position, first inversion, and second inversion. The inversions are created by moving the lowest note up an octave. Although the lowest note in the second chord is E and the lowest note in the third chord is G, these are both still C major chords.

Figure 3-8. Inverting an augmented triad produces a chord that sounds exactly the same as a different root-position augmented triad. When the C in example (a) is moved up an octave, the voicing contains a stacked augmented 3rd (E-G#) and diminished 4th (G#-C). The upper C, however, is enharmonically equivalent to the B# in an E augmented triad. The same thing happens in example (b): Inverting the E6 augmented triad produces the enharmonic equivalent of a G augmented triad.

The corollary to this is the fact that there are only four different augmented triads on the keyboard, not 12. The notes in the chords Caug, Eaug, and G#aug (or A6aug) are identical. The same is true for the three other sets of augmented triads. Here's the complete list of possibilities:

Caug = Eaug = G#aug

D6aug = Faug = Aaug

Daug = F#aug = B6aug

E6aug = Gaug = Baug

You can verify this for yourself by locating these triads on the keyboard and listening to the close similarity in their sounds.

OPEN & CLOSED VOICINGS

Instead of moving the bottom note of the chord up an octave, we can create a new voicing by moving one of the other notes up an octave - or by moving the bottom note down an octave. When we do this, there will be gaps in the chord voicing, as Figure 3-9 shows. Up to now, all of the triads we've looked at have been in closed position. This term (many music theorists prefer "close position") is a way of saying that the notes in the chord are as close together as they can get. The second chord in Figure 3-9, however, is in open position. In an open-position chord voicing, there are gaps into which other notes belonging to the chord could be inserted.

A triad can be played in a number of different open-position voicings. Figure 3-10 gives some examples. In each case, the lowest note of the voicing defines the inversion. If the lowest note is the 3rd of the chord, the voicing is in first inversion; if the lowest note is the 5th of the chord, the voicing is in second inversion; and if the lowest note is the root, the voicing is in root position.

Figure 3-9. A closed-position C major voicing (left) can be turned into an open-position voicing (right) by moving a note other than the lowest note up an octave. In an openposition voicing, there are gaps where other notes belonging to the chord could be played. The gaps are shown here by noteheads in parentheses.

Figure 3-10. An assortment of open-position voicings of a C major chord.

There are no names that I'm aware of for the various open-position voicings, but there is one loose rule that you might want to be aware of for forming these voicings. A gap of more than an octave between the lowest note (the bass voice) and the rest of the voicing is common, but chord voicings tend to feel disjointed or unstable if there are gaps wider than an octave between any of the upper notes. The third root-position voicing in Figure 3-10 violates this principle, but to my ears it sounds balanced, so I wouldn't hesitate to use it. Voicings like those in Figure 3-11, however, sound muddy, and most arrangers will avoid them except when they want a special effect.

As you might infer from what I've just said, revoicing a chord changes its sound quality - sometimes subtly, sometimes drastically. A vital aspect of learning to use chords is learning how the various voicings of a given chord sound. This is a concept you should play with, using your favorite chording instrument, as we explore more complex chords in later chapters. Don't just try the voicings shown: Revoice the chords in various ways.