A Scots Quair (2 page)

Authors: Lewis Grassic Gibbon

Â

If the great Dutch language disappeared from literary usage and a Dutchman wrote in German a story of the Lekside peasants, one may hazard he would ask and receive a certain latitude and forbearance in his usage of German. He might import into his pages some score or so untranslatable words and idiomsâuntranslatable except in their context and setting; he might mould in some fashion his German to the rhythms and cadence of the kindred speech that his peasants speak. Beyond that, in fairness to his hosts, he hardly could go: to seek effect by a spray of apostrophes would be both impertinence and mis-translation.

Â

The courtesy that the hypothetical Dutchman might receive from German a Scot may invoke from the great English tongue.

L.G.G.

Â

KINRADDIE lands had been won by a Norman childe, Cospatric de Gondeshil, in the days of William the Lyon, when gryphons and such-like beasts still roamed the Scots countryside and folk would waken in their beds to hear the children screaming, with a great wolf-beast, come through the hide window, tearing at their throats. In the Den of Kinraddie one such beast had its lair and by day it lay about the woods and the stench of it was awful to smell all over the countryside, and at gloaming a shepherd would see it, with its great wings half-folded across the great belly of it and its head, like the head of a meikle cock, but with the ears of a lion, poked over a fir tree, watching. And it ate up sheep and men and women and was a fair terror, and the King had his heralds cry a reward to whatever knight would ride and end the mischieving of the beast. So the Norman childe, Cospatric, that was young and landless and fell brave and well-armoured, mounted his horse in Edinburgh Town and came North, out of the foreign south parts, up through the Forest of Fife and into the pastures of Forfar and past Aberlemno's Meikle Stane that was raised when the Picts beat the Danes; and by it he stopped and looked at the figures, bright then and hardly faded even now, of the horses and the charging and the rout of those coarse foreign folk. And maybe he said a bit prayer by that Stone and then he rode into the Mearns, and the story tells no more of his riding but that at last come he did to Kinraddie, a tormented place, and they told him where the gryphon slept, down there in the Den of Kinraddie.

But in the daytime it hid in the woods and only at night, by a path through the hornbeams, might he come at it, squatting in bones, in its lair. And Cospatric waited for the night to come and rode to the edge of Kinraddie Den and commended his soul to God and came off his horse and took his boar-spear in his hand, and went down into the Den and killed the gryphon. And he sent the news to William the Lyon, sitting drinking the wine and fondling his bonny lemans in Edinburgh Town, and William made him the Knight of Kinraddie, and gave to him all the wide parish as his demesne and grant to build him a castle there, and wear the sign of a gryphon's head for a crest and keep down all beasts and coarse and wayward folk, him and the issue of his body for ever after.

So Cospatric got him the Pict folk to build a strong castle there in the lithe of the hills, with the Grampians bleak and dark behind it, and he had the Den drained and he married a Pict lady and got on her bairns and he lived there till he died. And his son took the name Kinraddie, and looked out one day from the castle wall and saw the Earl Marischal come marching up from the south to join the Highlandmen in the battle that was fought at Mondynes, where now the meal-mill stands; and he took out his men and fought there, but on which side they do not say, but maybe it was the winning one, they were aye gey and canny folk, the Kinraddies. And the great-grandson of Cospatric, he joined the English against the cateran Wallace, and when Wallace next came marching up from the southlands Kinraddie and other noble folk of that time they got them into Dunnottar Castle that stands out in the sea beyond Kinneff, well-builded and strong, and the sea splashes about it in the high tides and there the din of the gulls is a yammer night and day. Much of meal and meat and gear they took with them, and they laid themselves up there right strongly, they and their carles, and wasted all the Mearns that the Cateran who dared rebel against the fine English king might find no provision for his army of coarse and landless men. But Wallace came through the Howe right swiftly and he heard of Dunnottar and laid siege to it and it

was a right strong place and he had but small patience with strong places. So, in the dead of one night, when the thunder of the sea drowned the noise of his feint, he climbed the Dunnottar rocks and was over the wall, he and the vagabond Scots, and they took Dunnottar and put to the slaughter the noble folk gathered there, and all the English, and spoiled them of their meat and gear, and marched away.

Kinraddie Castle that year, they tell, had but a young bride new home and she had no issue of her body, and the months went by and she rode to the Abbey of Aberbrothock where the good Abbot, John, was her cousin, and told him of her trouble and how the line of Kinraddie was like to die. So he lay with her, that was September, and next year a boy was born to the young bride, and after that the Kinraddies paid no heed to wars and bickerings but sat them fast in their Castle lithe in the hills, with their gear and bonny leman queans and villeins libbed for service.

And when the First Reformation came and others came after it and some folk cried

Whiggam!

and some cried

Rome!

and some cried

The King!

the Kinraddies sat them quiet and decent and peaceable in their castle, and heeded never a fig the arguings of folk, for wars were unchancy things. But then Dutch William came, fair plain a fixture that none would move, and the Kinraddies were all for the Covenant then, they had aye had God's Covenant at heart, they said. So they builded a new kirk down where the chapel had stood, and builded a manse by it, there in the hiddle of the yews where the cateran Wallace had hid when the English put him to rout at last. And one Kinraddie, John Kinraddie, went south and became a great man in the London court, and was crony of the creatures Johnson and James Boswell; and once the two of them, John Kinraddie and James Boswell, came up to the Mearns on an idle ploy and sat drinking wine and making coarse talk far into the small hours night after night till the old laird wearied of them and then they would steal away and as James Boswell set in his diary,

Did get to the loft

where the maids were, and one

IIϵγγί ÎÏ

Î½Î´Î±Ï ÏÎ±Ï ÏÎ±Ï Î¹Î½ Thϵ βνÏÏockÏ Î±Ï

δ I διδλιâ wιÏh hϵÏ.

But in the early days of the nineteenth century it was an ill time for the Scots gentry, for the poison of the French Revolution came over the seas and crofters and common folk like that stood up and cried

Away to hell!

when the Auld Kirk preached submission from its pulpits. Up as far as Kinraddie came the poison and the young laird of that time, and he was Kenneth, he called himself a Jacobin and joined the Jacobin Club of Aberdeen and there at Aberdeen was nearly killed in the rioting, for liberty and equality and fraternity, he called it. And they carried him back to Kinraddie a cripple, but he would still have it that all men were free and equal and he set to selling the estate and sending the money to France, for he had a real good heart. And the crofters marched on Kinraddie Castle in a body and bashed in the windows of it, they thought equality should begin at home.

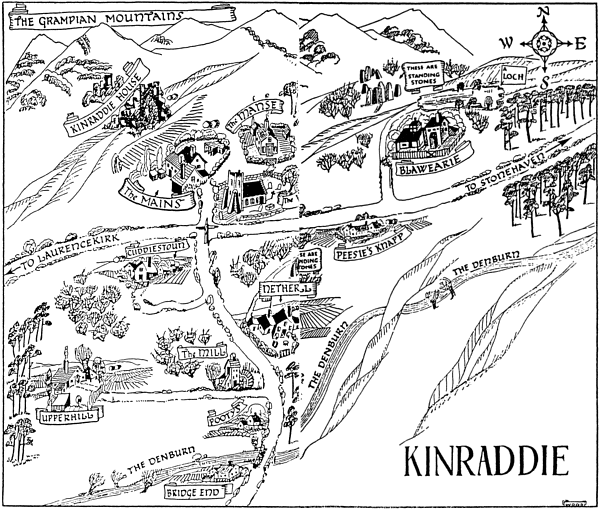

More than half the estate had gone in this driblet and that while the cripple sat and read his coarse French books; but nobody guessed that till he died and then his widow, poor woman, found herself own no more than the land that lay between the coarse hills, the Grampians, and the farms that stood out by the Bridge End above the Denburn, straddling the outward road. Maybe there were some twenty to thirty holdings in all, the crofters dour folk of the old Pict stock, they had no history, common folk, and ill-reared their biggings clustered and chaved amid the long, sloping fields. The leases were one-year, two-year, you worked from the blink of the day you were breeked to the flicker of the night they shrouded you, and the dirt of gentry sat and ate up your rents but you were as good as they were. So that was Kenneth's leaving to his lady body, she wept right sore over the pass that things had come to, but they kittled up before her own jaw was tied in a clout and they put her down in Kinraddie vault to lie by the side of her man. Three of her bairns were drowned at sea, fishing off the Bervie braes they had been, but the fourth, the boy Cospatric, him that died the same day as the Old Queen, he was douce and saving and sensible, and set putting the estate to rights. He threw out half the little tenants, they flitted off to Canada and Dundee

and parts like those, the others he couldn't move but slowly. But on the cleared land he had bigger steadings built and he let them at bigger rents and longer leases, he said the day of the fine big farm had come. And he had woods of fir and larch and pine planted to shield the long, bleak slopes, and might well have retrieved the Kinraddie fortunes but that he married a Morton quean with black blood in her, she smitted him and drove him to drink and death, that was the best way out. For his son was clean daft, they locked him up at last in an asylum, and that was the end of Kinraddie family, the Meikle House that stood where the Picts had builded Cospatric's castle crumbled to bits like a cheese, all but two- three rooms the trustees held as their offices, the estate was mortgaged to the hilt by then.

Â

SO BY THE WINTER

of nineteen eleven there were no more than nine bit places left the Kinraddie estate, the Mains the biggest of them, it had been the Castle home farm in the long past times. An Irish creature, Erbert Ellison was the name, ran the place for the trustees, he said, but if you might believe all the stories you heard he ran a hantle more silver into his own pouch than he ran into theirs. Well might you expect it, for once he'd been no more than a Dublin waiter, they said. That had been in the time before Lord Kinraddie, the daft one, had gone clean skite. He had been in Dublin, Lord Kinraddie, on some drunken ploy, and Ellison had brought his whisky for him and some said he had halved his bed with him. But folk would say anything. So the daftie took Ellison back with him to Kinraddie and made him his servant, and sometimes, when he was real drunk and the fairlies came sniftering out of the whisky bottles at him, he would throw a bottle at Ellison and shout

Get out, you bloody dish-clout!

so loud it was heard across at the Manse and fair affronted the minister's wife. And old Greig, him that had been the last minister there, he would glower across at Kinraddie House like John Knox at Holyrood, and say that God's hour would come. And sure as death it did, off to the asylum they hurled the daftie, he went with a nurse's mutch on his head

and he put his head out of the back of the waggon and said

Cockadoodledoo!

to some school bairns the waggon passed on the road and they all ran home and were fell frightened.

But Ellison had made himself well acquaint with farming and selling stock and most with buying horses, so the trustees they made him manager of the Mains, and he moved into the Mains farmhouse and looked him round for a wife. Some would have nothing to do with him, a poor creature of an Irishman who couldn't speak right and didn't belong to the Kirk, but Ella White she was not so particular and was fell long in the tooth herself. So when Ellison came to her at the harvest ball in Auchinblae and cried

Can I see you home

to-night, me dear?

she said

Och, Ay.

And on the road home they lay among the stooks and maybe Ellison did this and that to make sure of getting her, he was fair desperate for any woman by then. They were married next New Year's Day, and Ellison had begun to think himself a gey man in Kinraddie, and maybe one of the gentry. But the bothy billies, the ploughmen and the orra men of the Mains, they'd never a care for gentry except to mock at them and on the eve of Ellison's wedding they took him as he was going into his house and took off his breeks and tarred his dowp and the soles of his feet and stuck feathers on them and then they threw him into the water-trough, as was the custom. And he called them

Bloody Scotch savages

, and was in an awful rage and at the term-time he had them sacked, the whole jing-bang of them, so sore affronted he had been.

But after that he got on well enough, him and his mistress, Ella White, and they had a daughter, a scrawny bit quean they thought over good to go to the Auchinblae School, so off she went to Stonehaven Academy and was taught to be right brave and swing about in the gymnasium there with wee black breeks on under her skirt. Ellison himself began to get well-stomached, and he had a red face, big and sappy, and eyes like a cat, green eyes, and his mouser hung down each side of a fair bit mouth that was chokeful up of false teeth, awful expensive and bonny, lined with bits of gold. And he aye wore leggings and riding breeks, for he was fair gentry by

then; and when he would meet a crony at a mart he would cry

Sure, bot it's you, thin, ould chep!

and the billy would redden up, real ashamed, but wouldn't dare say anything, for he wasn't a man you'd offend. In politics he said he was a Conservative but everybody in Kinraddie knew that meant he was a Tory and the bairns of Strachan, him that farmed the Peesie's Knapp, they would scraich out

Inky poo, your nose is blue,

You're awful like the Turra Coo!

whenever they saw Ellison go by. For he'd sent a subscription to the creature up Turriff way whose cow had been sold to pay his Insurance, and folk said it was no more than a show off, the Cow creature and Ellison both; and they laughed at him behind his back.

Â

SO THAT WAS THE

Mains, below the Meikle House, and Ellison farmed it in his Irish way and right opposite, hidden away among their yews, were kirk and manse, the kirk an old, draughty place and in the winter-time, right in the middle of the Lord's Prayer, maybe, you'd hear an outbreak of hoasts fit to lift off the roof, and Miss Sarah Sinclair, her that came from Netherhill and played the organ, she'd sneeze into her hymn-book and miss her bit notes and the minister, him that was the old one, he'd glower down at her more like John Knox than ever. Next door the kirk was an olden tower, built in the time of the Roman Catholics, the coarse creatures, and it was fell old and wasn't used any more except by the cushat- doves and they flew in and out the narrow slits in the upper storey and nested there all the year round and the place was fair white with their dung. In the lower half of the tower was an effigy-thing of Cospatric de Gondeshil, him that killed the gryphon, lying on his back with his arms crossed and a daft- like simper on his face; and the spear he killed the gryphon with was locked in a kist there, or so some said, but others said it was no more than an old bit heuch from the times of Bonny Prince Charlie. So that was the tower, but it wasn't fairly a part of the kirk, the real kirk was split in two bits, the main hall and the wee hall, and some called them the byre and

the turnip-shed, and the pulpit stood midway. Once the wee hall had been for the folk from the Meikle House and their guests and such-like gentry but nearly anybody that had the face went ben and sat there now, and the elders sat with the collection bags, and young Murray, him that blew the organ for Sarah Sinclair. It had fine glass windows, awful old, the wee hall, with three bit creatures of queans, not very decent- like in a kirk, as window-pictures. One of the queans was Faith, and faith she looked a daft-like keek for she was lifting up her hands and her eyes like a heifer choked on a turnip and the bit blanket round her shoulders was falling off her but she didn't seem to heed, and there was a swither of scrolls and fiddley-faddles all about her. And the second quean was Hope and she was near as unco as Faith, but had right bonny hair, red hair, though maybe you'd call it auburn, and in the winter-time the light in the morning service would come splashing through the yews in the kirkyard and into the wee hall through the red hair of Hope. And the third quean was Charity, with a lot of naked bairns at her feet and she looked a fine and decent-like woman, for all that she was tied about with such daft-like clouts.