A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (2 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

It was autumn 1962.

The Cuban Missile Crisis threatened to end the world as we knew it. As Kennedy and Khrushchev teetered on the brink, it became startlingly clear that not only was an apocalyptic end within our technological means, it was also an immediate likelihood. The fear of incoming Soviet nuclear-tipped missiles meant schoolchildren across America were learning to duck and take cover under their desks while their parents dug bomb shelters they believed would take them to the other side of the looming apocalypse.

During those same tense days in October 1962 and half a world away, a charismatic and visionary Tibetan lama was leading over 300 followers into the snow and glaciers of the high Himalayas in order to ‘open the way’ to a hidden valley of immortality that Tibetan scriptures dating back to the twelfth century describe as a place of unimaginable peace and plenty that can be opened only at a time of the most dire need, when cataclysm racks the earth and there is nowhere else to run.

This book tells their true story.

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER ONE

A Crack in the World

‘There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.’ ~Leonard Cohen

‘You’re a writer—you like stories? My mother-in-law has a story from when she was young, a story of a journey she took into the glaciers of the high Himalayas. You might think it’s fiction—the imaginings of an old woman—but I assure you it is not. It will make you question your sense of reality.’

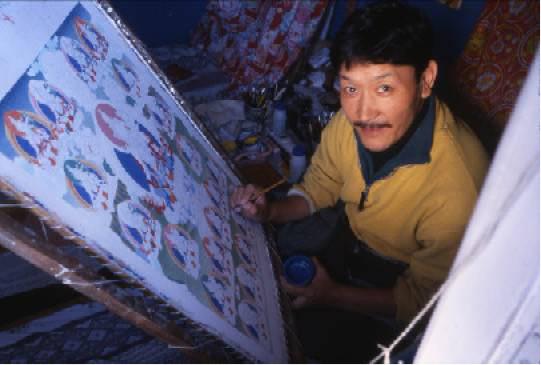

It was with these words that my friend Tinley set this book in motion. Tinley is a master painter of

thangkas

—the Tibetan religious scroll paintings depicting the tantric deities and various Buddhas in their myriad forms. He was crushing a blue semi-precious stone acquired from Tibet to match a patch of sky he was fixing on an antique

thangka

belonging to Sikkim’s royal family, which was stretched taut on a wooden frame. He was sitting cross-legged on a rug in his studio in Gangtok, the capital of the Indian state of Sikkim, a once-independent Himalayan kingdom. I was sitting opposite, leaning against the wall and watching him work.

Tinley Gyatso, in his studio in Gangtok, Sikkim

The son of Tibetan refugees, Tinley grew up at the Tibetan Refugee Self-Help Center in Darjeeling. He was around forty when I met him, and lived with his wife, son and mother-in-law on the top floor of a building called the Light of Sikkim in the center of Gangtok. He painted, had painting apprentices and, with his wife, ran a small cyber café.

I had been introduced to his mother-in-law, a woman of seventy-five who was often leaning on the wide railing of their rooftop flat looking out over the city and the mountains beyond, spinning her prayer wheel and reciting mantras. Three years earlier she had shaved her head, donned a robe and become a nun in order to devote herself more fully to the religious life. Often when I visited, I would stand next to her and lean on the railing looking over the city and snow mountains beyond, stilled by her calm presence. I did not know much about her beyond that presence, since she spoke not a word of English and I speak neither Tibetan nor Bhutanese.

‘How can her journey into the mountains make me question my sense of reality?’ I asked Tinley.

He laughed. ‘It’s better she tells you herself,’ he said.

‘But—’

‘Trust me,’ Tinley said, looking up from the powder in his mortar and pestle, which was as blue as the empty Tibetan sky. He looked me in the eye: ‘I tell you—it will stretch your sense of what’s possible. You’ll think she’s spun the tale in her head. But it’s entirely true.’

‘What’s entirely true?’

‘That’s for her to say!’ he laughed. ‘She’s away for a few days now on a retreat in a monastery in western Sikkim but she’ll be back tomorrow. Why don’t you come the day after in the afternoon?’

I arrived at the appointed time with my tape recorder.

Tinley called his mother-in-law.

She walked into the room dressed in her nun’s robes. One hand was working the beads of her mala, a Tibetan rosary, and the other she ran across the stubble of her shaved head and smiled when she saw me. I had been away from Sikkim and hadn’t seen her in almost a year. She said something in Tibetan and Tinley interpreted: ‘She said that since you are meeting again after such a long time, it means you still have karma together. Otherwise you wouldn’t be meeting again.’

‘It must be that story,’ I said, laughing.

‘It is a story that has changed many people’s fates,’ Tinley said, with an enigmatic twinkle in his eye. ‘We’ll see what happens to you.’

Tinley made tea. The three of us sat on the floor, and with Tinley translating she told me a story that certainly changed the course of the next four years of my life. Her story was pithy and replete with rustic details of crevasses, streams and high snow peaks—the vividness of which was remarkable for the passage of over four decades. What struck me most was the depth and passion of her faith.

Dorje Wangmo

She began by telling me that she was from Bhutan. She and her husband had a small farm—a few cows, chickens, and they grew their own grain. Even as a child she had heard that there was a place called Beyul Demoshong, a hidden valley in Sikkim she described as a heaven you enter through a cave, a place where you would live forever. This valley is on the slopes of Mount Kanchenjunga. In a matter-of-fact manner, as if she were telling me that she had a hundred rupees stashed under her mattress, she told me that half the wealth of this world and great stores of what she called spiritual attainment were hidden inside the mountain. ‘Why do you think it is so peaceful here in Sikkim and there is so much happiness?’ she asked, her eyes clear and penetrating. ‘It is because we are living so close to Mount Kanchenjunga.’

Sipping her tea, spinning her prayer wheel and looking off into the distance she recalled her childhood: ‘My village lama back in Bhutan used to tell us, and our parents told us too, “There is a cave, and there are people who have made it.” There was a man from Tibet who went to Sikkim. He was high in the mountains when there was a big snowfall and he got lost. He saw a cave, and he went inside for refuge. It was so beautiful that he could never explain it in words. He went inside for maybe twenty minutes, and when he came out years had passed without his knowing, and zip-zip—he was old. Old age in a moment!’

Dorje Wangmo laughed, not because of the unreality of her tale but because of the incredulity she saw on my face.

‘I didn’t meet this man,’ she said. ‘I only heard his story.’

As she spun her prayer wheel thoughtfully, she explained that the story was unusual and must be based on the man’s special karma. ‘Usually you cannot just go there, on your own,’ she said. ‘It has to be “opened” by a special type of Tibetan Buddhist lama.’

Tinley explained that this special type of lama is called a terton, or treasure revealer. A few of these visionary lamas had attempted the opening but their karma wasn’t right. Obstacles came in their way and they failed.

Dorje Wangmo was thirty-six when she heard that the lama who had all the signs had come. His name was Tulshuk Lingpa. Though he was from Tibet, he was staying at the Tashiding Monastery, which was considered the auspicious holy center of the Kingdom of Sikkim. It was there that it was prophesied the lama would make his appearance.

She recalled for me her departure: ‘A monk-brother of mine—he wasn’t really my brother but all followers of the dharma are like brothers and sisters—was going to Sikkim to be there when the lama opened the way. When he told me, a tremendous feeling of longing awoke within me. I didn’t want to be left out. So I told my husband “If you want to go, let’s go together. If you don’t want to go, I’ll go by myself.”

‘“What?” my husband said. “You must be crazy!”’

Dorje Wangmo chuckled at the recollection and spun her prayer wheel a little faster. Her old eyes glinted.

‘“It doesn’t matter,” I told him. “I’m going—whether you come or not.”

‘“Then I’ll go, too,” he said.

‘We gave away our house and fields. We sold enough so we had the money to make the journey, and the rest we gave away. What use would we have for extra money? In Beyul there would always be food; you wouldn’t have a care. And once you enter Beyul, you’ll never leave. Who’d want to? Our tickets were all one-way. All tickets to Beyul are one-way.’

Dorje Wangmo laughed so long and hard it was infectious.

By the time they got to Tashiding—it took over two weeks to get there in those days—the lama had already left with his hundreds of followers to open the way. So they set off immediately, north to Mount Kanchenjunga. They stopped at Yoksum, the last village on the way, and bought enough food for the long journey: a sack each of ground corn, wheat and

tsampa

, the roasted barley flour the peoples of the high Himalayas never tire of eating. They wet the flour with tea and butter or sometimes just water, form it into balls of moist dough and pop them into their mouths.

Both the men she ‘chose’ for the journey, her husband and her monk-brother, were not really fit for mountain travel. They tired quickly, with the sacks of food they had to carry, the bedding and everything else. Their faith wasn’t as great as hers. ‘What was the weight of a bedroll,’ she asked, ‘when you were on your way to the Hidden Land? We had been waiting for generations.’

They found themselves on the edge of the snow. Though she was the woman, she went in front to cut the way when the snow came up to their hips. She even made steps in the snow for them. They hadn’t a clue what secret trails the lama had taken to find this hidden place, and the mountain was huge—stretching from Sikkim to Nepal and Tibet. Sometimes they came upon stones stacked on top of each other. They believed the lama left those stones to mark the way. So when they saw them, they followed them—and into the snow and windswept heights they went.

After a few days her monk-brother gave up and went back to Yoksum. He had begun to fear the heights, which made his mind play tricks on him and he began to have doubts. Now there was more for her and her husband to carry. They would take two of the sacks a kilometer ahead, hide them in a cave or cliff for safekeeping and go back for the third. They also had with them a small bag of dried fish. But if they fried them in the fire they would smoke and the mountain gods would get upset. So they kept them in the bag in case of emergency.

The next day they met a Sikkimese couple who were felling a tree over a rushing stream to make the crossing. A baby was strapped to the woman’s back. They were also looking for the lama. They had a donkey but hardly a handful of food, which impressed Dorje Wangmo greatly: only someone with tremendous faith would venture into such high mountains without food. It was because of this she agreed to continue their search together. They shared their food with them and put the sacks of food on the donkey, which made it easier especially since they had heard from some nomads that the lama was on the Nepal side—the mountain straddles the Sikkim–Nepal border—and they had to cross a high and snowy pass to get there. Soon they came upon others and yet others, all looking for the lama. The band of pilgrims became a dozen strong: three children, four women and five men.