A Step Away from Paradise: A Tibetan Lama's Extraordinary Journey to a Land of Immortality (3 page)

Authors: Thomas Shor

They had to cross a glacier on their way to the pass and it became extremely dangerous. Deep cracks in the glacial ice were hidden under newly fallen snow. While they knew how to tell when the snow was hiding a crack, the donkey didn’t. It stepped on to a thin layer of frozen snow and fell into a very deep crack. Held only by its lead rope it dangled over the deep, braying. Two of the sacks fell from the donkey’s back and disappeared forever without a sound into the huge crack. They were able to rescue the third. It was the sack of

tsampa

. Then, with three of them pulling on its rope and two others grabbing its neck and legs, they were somehow able to haul the donkey to safety.

That night there was a huge snowstorm with a tremendous wind, and since they had no shelter they had to sleep huddled together beneath their jackets and blankets. They had nothing to eat but

tsampa

. Not even water. So they ate dry

tsampa

with melted snow in their mouths.

Tsampa

and snow—that’s all they had.

The next morning they fanned out to search for shelter. Dorje Wangmo found a cave about a kilometer away into which they all could easily fit. They spent two days in that cave eating dry

tsampa

and melted snow while the howling wind blew blinding snow outside. The weather in high mountains, she explained, is controlled by the mountain gods, and they were clearly not happy with the intrusion of this band of human beings into their realm. They offered prayers to the gods, prostrated and burned incense.

On the third day, they awoke to sunshine. But the snow was so deep it was impossible to walk through, especially with the children. They hardly knew which way to go. Since their

tsampa

wouldn’t last long, Dorje Wangmo decided some of them would have to go ahead and try to find the lama and his followers, or at least some nomads who could spare a little food. She chose the two strongest men to come with her. The newly fallen snow hid all but the widest crevasses, making the way all the more treacherous. They left before sunrise when the snow was the hardest and would be more likely not to give way. It was Dorje who chose the direction and broke the trail.

Tinley broke his almost simultaneous translation to interject his own observation. ‘She’s a powerful mother-in-law,’ he said with a twinkle, ‘a real warrior. Even her name Wangmo means The Powerful One.’

When they reached the first settlement in Nepal they heard that the lama and his followers were at a monastery farther down. He hadn’t yet opened the secret cave. So they cut some grass for the donkey, filled a sack with cooked potatoes and climbed back over the pass to where the others were waiting in the cave. The next day, she led the others across the pass on the trail she had cut. It took two days for them to reach the lama. For a few months the lama was busy doing special pujas, or rituals, to appease the local spirits. Then he led hundreds of them high into the mountains in order to open what she called the Gate of Heaven.

With that she got up. To my amazement, night had fallen. A glance at my watch told me almost three hours had passed.

‘That’s how it was,’ she said. ‘If I were still young I’d show you the way. But now I can hardly walk. My legs hurt and my feet are swollen.’ She bent down and rubbed her left knee and looked at her bare feet, gnarled with arthritis.

‘Just look at my feet,’ she said. ‘See what time has done to them. And to think I was the one to walk in front and stamp down the snow! Now all I can do is pray.’ She spun her prayer wheel, and muttering the mantra of Padmasambhava beneath her breath she left the room.

The secret cave

Wall painting, Tashiding Gompa, Sikkim

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER TWO

Into the Rabbit Hole

‘I became one of the lucky ones—I reached my unattainable land.’ ~ Carl Gustav Jung

When I stepped into the Gangtok night I felt elated. Just by being in Dorje Wangmo’s presence, hearing her very real story, feeling the icy, snow-laden winds she described, I felt a longing awaken within me like a distant echo.

How extraordinary it is to actually meet someone with the courage not only to believe in a land of dreams but to leave everything behind for it.

‘Only if you are willing to give up everything and leave forever,’ she had told me, ‘only then can you go to the beyul.’

Dorje Wangmo left her native Bhutan and never returned. She gladly gave up not only her possessions but was quite willing to say goodbye to everyone she had ever known, so infinitely greater was the place to which she was going.

I found myself at a high point in the city. Perhaps it was the altitude or maybe the lowness of the clouds that somehow made the sky seem more immediate, not entirely disconnected from where I stood. The firmament of stars seemed almost close enough to touch.

The moon shot free of the swiftly moving, tumbling clouds. Across a deep and broad valley rose ridges of thickly wooded hills. Ascending in the distance were the snow-clad heights of Mount Kanchenjunga. There, basking in the same silvery moonlight, were the very snowy slopes Dorje Wangmo had spoken of so vividly.

Maybe I was confounding the palpable detail with which she told her tale—vivid to the tiniest particular—for the reality of that which she sought but I felt the need to delve deeper into the story.

I went back to see Dorje Wangmo the next morning to ask if she knew of others who had gone with Tulshuk Lingpa on his journey to Beyul. She told me of two people who, in turn, told me of others, and eventually the search for those who set out for Beyul brought me to villages, monasteries and mountain retreats from Darjeeling and Sikkim in the eastern Himalayas to the western Himalayas and to Nepal. I met and spent time with most of the surviving members of the expedition, now mostly quite aged, as well as the lama’s family. These extraordinary people, who gave up everything to follow their dreams, also gave freely of their time to tell me about what was for most of them the most extraordinary events of their lives.

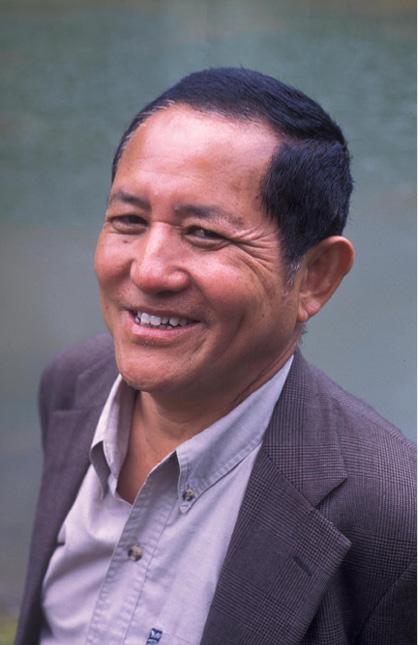

The most important person with whom I spoke was Kunsang, Tulshuk Lingpa’s only son. He provided the thread that wove together the story of Tulshuk Lingpa and his visionary expedition. Eighteen years old at the time his father departed for Beyul, Kunsang was able to offer a first¬hand account of what others knew only from hearsay. Kunsang heard the stories of Tulshuk Lingpa’s early life directly from him. One might expect—and even forgive—a son to exaggerate his father’s deeds. But the details of his stories, no matter how fantastic, astonished me all the more by checking out when I asked others who were in a position to know. Kunsang’s respect and admiration for his father was matched by his profound knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism. Deep respect did not preclude his seeing the humor and divinely inspired madness at the core of so many of the stories. With Kunsang alone I had almost fifty hours of taped interviews. When I transcribed these interviews, I was struck by the amount of time speech was rendered impossible by laughter.

Kunsang, Tulshuk Lingpa’s only son

I used to wonder just where to draw the line when Kunsang told his tales. Often I had the feeling he was leading me down a narrow plank over deepening water, drawing me further than I felt comfortable to a place where logic failed. His stories often started out on firm enough ground but as the incidents built up and became increasingly fantastic, I’d suddenly find myself following with my credulity intact further than I would normally go. I would end up believing things that if told outright would sound just too fantastic to have occurred. Every time I thought Kunsang had gone too far, I’d find a corroborating detail in something someone else said. Or I’d check details of what others told me with him, and find an uncanny concurrence of facts even in the most outlandish stories.

With Kunsang, one got a taste of what his father was like, making reality of things usually relegated to the realm of fiction and imagination. He wasn’t confounding fact and fiction as much as forging a new synthesis of the two.

We have been taught from the earliest age to separate fact from fiction. We can read

Alice in Wonderland

and get transported to a land of marvels. Yet while we are there, we know Wonderland doesn’t really exist. By imagining it, we partake in the hidden realm of wonders the author imagined but we retain our sense of propriety. We don’t redraw the line between fact and fiction; we suspend it, and we are entertained. That is certainly the prudent thing to do. We can assume it is what Lewis Carroll himself did. He could write his books about Wonderland and still maintain his position as a respected Oxford don.

Imagine what would have happened if Lewis Carroll had proclaimed the reality of Wonderland and launched an expedition? Surely he would have been thought mad as a hatter in the Oxford of his day as he would be today. The line separating fact from fiction is certainly tightly drawn and enduring—as tightly drawn as that which separates sane from insane. Cross one, and you cross the other.