A Thousand Laurie Lees (11 page)

Read A Thousand Laurie Lees Online

Authors: Adam Horovitz

School was a relief, once I had extracted myself from the local boys’ grammar school, too brutish and testosterone-fuelled a place for a thirteen-year-old still grieving the loss of his mother. Instead, I went to Archway, the mixed comprehensive with a radical staff, the school where my mother had taught eight years before. I was welcomed in by teachers who had known her well, but none of whom made that fact explicit for at least a couple of years, which helped the process of settling in no end.

More important, there were friends to be made, new confidantes as well as old allies. Skanda Huggins was there, a year below me in school years but the first person I called and told when I was accepted there. New friends were made – Mackie, Giz, Legzee, Joe, Matthew Chadwick and Mathew Shaw (with both of whom I’d hunted for Easter eggs at Diana Lodge’s house years before), plus Euan and many more. We bonded mostly over music, and my ability to concentrate slipped a gear thanks to late-night sessions of listening to John Peel on BBC Radio 1.

Music became as essential to me as breathing at about fourteen, as it has for huge numbers of British teenagers born post-Second World War. I ripped up the cottage with anything from Prince to Charlie Mingus, the Dead Kennedys to The The, raiding Woolworths and the Trading Post in Stroud with my pocket money after school, or ransacking my father’s record collection for something – anything – new, straining through the lyrics for inspiration and points of identification and jumping to the rhythms that Slad and the valley could not or would not provide.

My father, when lost in his attic with work, would hammer away at his typewriter in competition with the chattering bird we never accurately identified (although we suspected it might be a blackbird) and which we dubbed the typewriter bird as it seemed to want to talk back to his erratically speedy, one-finger typing from the nearest treetop. Often he would yell down the stairs for some peace, for the space to think clearly as I span records on the tired old blue and white Dansette, which allowed me to play singles at 16 or 78rpm, much to my amusement and my father’s regular annoyance.

Eventually the Dansette wore out and even my father, who was happy enough for me to be playing Mingus every so often, even if he noisily pretended to object to Prince or the post-punk and electronica I began to discover going cheap at car boot sales, decided we should get a new record player. The trouble was, as ever, that money was tight, so we looked in the local paper for weeks, eventually finding a cheap but cheerful looking player someone was advertising. We phoned and asked if we could come and try it. The sellers said yes, of course.

The next difficulty was how to get there. My father had never learned to drive; his only two attempts had nearly ended in disaster: first in Ireland when he had myopically come close to running the car into a couple of cows on a road trip visiting poets and second when my mother, in despair of being the only driver in the house had, in the early 1970s, tried to get him to drive out of the valley, up the steep hill that ran behind our house and round the hairpin bend that has terrified even the calmest of drivers who have come at it unwary over the years. That time, the car nearly tipped over the edge and back down the hill onto our house. My mother commanded him to never drive again.

This didn’t make it easy to live in the valley – getting to school in Stroud was a mission that involved waking at 6 a.m., with or before the dawn as a farm worker would have, and cycling two miles to the bus, which as I got older I invariably missed. Even getting post out was a trial and given that my father was sending out magazines on mail order, and could rarely spare the time away from his typewriter to walk over-burdened with post to the nearest tiny letterbox, neighbours had to be asked. A small community will willingly give help when help is needed, but favours need to be spread out. I remember my father checking the back of Alan Lloyd’s Land Rover for the letters he’d asked Alan to post, and which Alan often forgot, sometimes quite deliberately. Getting shopping back was an equally arduous task.

The Lloyds were long gone, however, and there were new residents in their long, strangely Alpine cottage. Hugh Padgham, with whom I was impressed because he talked music with me occasionally as if my tastes mattered, had moved in not long after I came back to the valley. I remember him at one of our first encounters being cheerfully derisive of the Madonna badge I was wearing. On looking closer, he told me that I at least had

some

good taste. I was also wearing a Sting badge, entirely unaware that Hugh had just produced the album the badge was promoting, and that he had produced The Police.

My father, wondering how to get to the house wherein the record player was waiting, had an epiphany. He picked up the phone.

‘Hi Hugh,’ he said. ‘May I ask a favour?’

A moment’s silence, then: ‘Well, we’ve found a second hand record player for sale and I was hoping we might be able to get a lift to test it out. Since you’re here this weekend, I hoped you might be able to take us, as you know quite a bit about record players.’

The conversation went on a little while, my father’s charm offensive picking up apace, until finally Hugh closed the dialogue with the suggestion that we find a record with which to test the player when we got there.

Hugh greeted us with what seems to me now to be a gently arch, friendly amusement at the top of the hill some hours later, and drove us off to see the record player. It wasn’t the most comfortable of rides for me. I was all too easily embarrassed by my father’s persuasions and felt discomfited by the idea that the producer of The Police was being dragged along to help us buy a cheap record player because he ‘knew about this sort of thing’.

Hugh, to be fair, seemed to let the whole thing breeze past him until we got to the house, where my father introduced him to the record player’s owner with all due pomp and I withered a little more. The owner got the record player started and I put on the record I had chosen to bring. It was

Unknown Pleasure,

by Joy Division, which I had found at a car boot sale the week before and was desperate to play.

‘What do you think?’ my father asked Hugh, referring to the record player.

‘It’s all right, if you like that sort of thing,’ said Hugh, referring to the album, which was just the sort of dark and monumentally, majestically tortured music favoured by a sixteen-year-old of melancholic disposition. Madonna and Sting were long gone from my affections by this time.

I said nothing, withering still more. The album sounded fine, if a little thin on the cheap, tinny but fairly functional record player. We bought the machine. My music collection lived to shout down birdsong and my father’s attempts to work another day. I don’t recall that we ever asked a similar favour of Hugh again.

It was hard to get excited by music four miles out of the teenage social whirl of a small town, where there’s too often little else to do but listen to music in company and get mutually excited about it. I wasn’t particularly musical, and could not have busked round Spain as Laurie Lee had, having learned the violin as a child. Although Inge loaned me a trumpet and tried to help me learn it, I gave up because it was too awkward to take to school on the back of my bicycle. A trumpet needed accompaniment, the added textures of people and instruments, to get me excited by its sound. Laurie, with a violin, could make music purely for himself, or with others, as he pleased.

The big bands had also long since stopped coming to Stroud. The Beatles’ worst gig was in Stroud’s Subscription Rooms in the month they made it big, Paul McCartney has gone on record as saying (although several people’s favourite aunties were apparently walked home by Macca that night). U2 are notoriously supposed to have played to the proverbial three men and an asthmatic dog in the Marshall Rooms just before they became huge.

So it was fortunate that my father needed to go to London regularly for work and arranged for me to stay with friends dotted around the five valleys of Stroud; with the Mackintoshes, the Huggins family and with the Lloyds, who soon moved to the other end of the Slad Valley, into a bungalow that Alan began to do up, as he had done with many properties since they left the house above me in the valley in 1980. I found music any way I could.

I had come back to the valley with a handful of memories and poems – by my parents, by Laurie Lee, Dylan Thomas and Charles Causley – locked in my head as the only reminders of childhood, ripe as just plucked plums on my tongue. With a gang of friends and places to stay, the valley’s people finally began to come to life around me again, a wider spectrum of people and influences to show me how much the place had changed. And then, suddenly, Laurie was there again, marking the way.

9

L

aurie seemed to appear over the horizon with surprising regularity after my return. First, we held a party in 1985 to celebrate birthdays and returns, and a party in the valley wasn’t quite a party without Laurie. The garden, rougher now than it had been when my mother was alive, and no longer given over to vegetables since my father was going too regularly to London for work to risk the expense of growing food and forgetting to water it and tend its stems against the constant hordes of slug and rabbit, badger and the occasional, tentative, greedy deer, became a rolling picnic table we had laid out in a panic, spreading our erratic party wares across the strimmed and hewn-down expanses of woodland undergrowth.

Old friends were there in abundance; Diana Lodge stomped over the valley from Trillgate, the Lloyds came back down to the valley for the day, Jane Percival came with her daughters, and if she smoked while she was there it was far down the garden and out of scent, away from my father’s disapproving glare.

Laurie’s arrival, with his wife Kathy, garrulous and dressed in white, caused the usual stir. Laurie announced his presence in our front room with a cheerful abandonment, filling the room with a personality as wide and welcoming and mischievous as his outstretched arms. I was on hand with a camera and caught him as he stretched out in greeting, his flies undone and a huge smile on his face.

‘Are you writing?’ he asked me later, once someone had pointed out his exposed underpants with a friendly laugh and the offer of a drink. He was perched on a stool, and I felt a little overawed.

‘A little,’ I said. ‘I’m going to a summer class with Gillian Clarke in a few weeks.’

I pointed Gillian out, my mother’s close friend who had on instinct travelled up to London the day before she’d died to see her, thinking it might be the last chance she had. She had come down from Wales for the day to celebrate with us and also to make sure I was settling in acceptably with my father.

‘Ah, writing classes,’ said Laurie, and he raised his eyebrows and smiled. ‘Do you need them when you’ve got all this?’

He gestured to the party, the valley, the world at large, his drink slopping a little, like late winter sunlight over the edge of his glass.

I wanted to say that it was the class my mother had taught before she died, that it kept me focused, that it was a connection to her. Before any words could leave my lips, Laurie pressed his hand to my shoulder, smiled again and was gone for a refresher, to talk to others. I slipped back into the party and to other friends, looking to the valley with new eyes.

I dug out Laurie’s poems again after this, exploring the recent edition of his

Selected Poems

I had found on my father’s shelves, looking for further clues to his meaning. In ‘The Abandoned Shade’ I found these lines:

Season and landscape’s liturgy,

badger and sneeze of rain,

the bleat of bats, the bounce of rabbits

bubbling under the hill:

Each old and echo-salted tongue

sings to my backward glance;

but the voice of the boy, the boy I seek,

within my mouth is dumb.

So I made the valley my study, at the expense of school, even so far as to take my war with mathematics to a ritualistic extreme, carrying my hated maths homework book out into the woods and burning it with hysterical ceremony on a pyre, shouting a curse on all algebra into the slow dusk as moths came battering their way towards the flames. I sought out the voice of the boy I had been, a process that continues as surely as the stream runs under the bridge, as seasons shift and find new ways to express themselves.

It paid off, this study of landscape, became, three years later, the first poem I wrote that marked for me the change up from the pretty poems of childish preoccupation and the bleak angst of teenage fear (although it combines elements of each). It was written on one of Gillian’s courses, but it looked back at the Slad Valley with a keener eye than I had managed before.

A

N

O

WL

B

REAKS THE

S

ILENCE

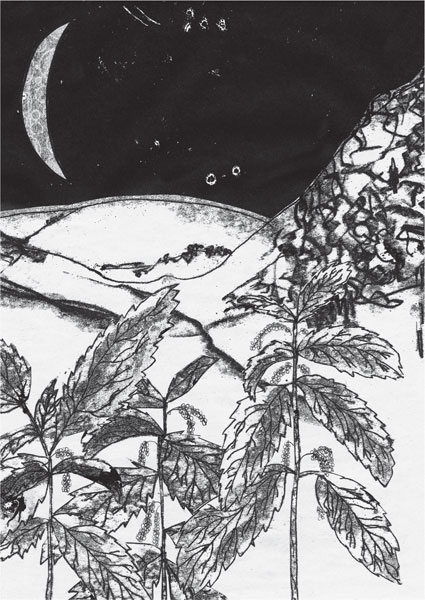

In the deepening contrast

between night and day

when an owl breaks the silence

and the foxes bay

when the chattering chaffinch

lays down its tune