A Time to Stand (12 page)

Authors: Walter Lord

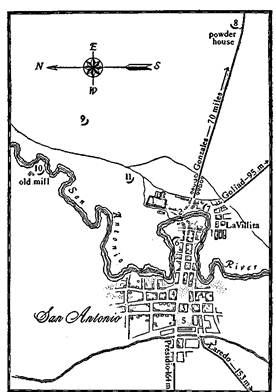

The siege tightens, February 23-March 5. (1) The Alamo; (2) the footbridge, scene of abortive parley on the 23rd; (3) San Fernando Church, where Santa Anna raised his red flag; (4) the Yturri house on Main Plaza, where he established his headquarters; (5) Military Plaza; (6) to (10) batteries described by Travis on March 3; (11) battery planted within 250 yards of Alamo on March 4, and later pushed still closer.

Martin walked to the river … met the smooth-as-syrup Colonel Almonte on the small footbridge just above Potrero Street. He explained that he was speaking for Travis, that if Almonte wanted to talk matters over, Travis would receive him “with much pleasure.”

Officially, Almonte explained that “it did not become the Mexican government to make any propositions through me” … that he was there only to listen. Unofficially, he apparently stressed that the Texans’ only hope was to surrender; but if they did lay down their arms—promising never to take them up again—their lives and property would be spared. After an hour’s talk, Martin said he would return with Travis if the Texans agreed to the Mexican terms; otherwise they would resume fire.

Martin trudged back to the Alamo, and the reply came in the form of another shattering blast from the big 18-pounder. As Travis tersely reported in a message to Houston, “I answered them with a cannon shot.”

As evening approached, strange noises replaced the usual sounds of San Antonio. Men stacking rifles … unhitching horses … fumbling with mess gear. In the Veramendi yard soldiers sweated with picks and shovels at an earthwork for the 5-inch howitzer. At the Nixon house Colonel Almonte pored over the inventory of captured matériel. What a disappointment—items like that barrel of pecans; all of it together worth no more than 3,000 pesos. Far more intriguing were the papers taken from John W. Smith’s quarters: piles of maps and plans and lists of names, odd work for a simple carpenter.

In Main Plaza Santa Anna himself wearily dismounted, handed the reins to an orderly, went into the Yturri house on the northwest corner. A flat-roofed, one-story building like most others in San Antonio, it didn’t make much of a headquarters. But at least it was strong; the Texans themselves had used it as an outpost.

The Mexican leader turned immediately to the task of organizing a siege. Yes, there must be a military government. Yes, Francisco Ruiz could stay on as

alcalde;

he seemed cooperative whoever held the town.

Outside, the darkened streets seemed almost gloomy. Gone were the tinkling guitars, the laughter and firelit yards. Here and there, people slipped along in the shadows, quietly bent on some mysterious errand. At Gregorio Esparza’s house, all was suppressed excitement. Swiftly the family gathered a few things, collected their three children and made off into the dusk. Across the river by the ford, they turned left and headed for the Alamo.

The crumbling old mission was battened down now, silent in the dying light of day. Below the walls the Esparzas waited, while unseen sentries studied them closely. Nothing to worry about here—Gregorio Esparza was one of Seguin’s best men, one of the few local Mexicans who could handle artillery. For some unknown reason the family had been delayed until now, but they were no less welcome.

A window in the church opened and one by one the Esparzas were lifted up and through. Twelve-year-old Enrique, tiny but alert and knowledgeable, stumbled over a cannon just inside the window. Finally they were all inside —the last of the defenders to retire to the Alamo.

In the headquarters room Travis and Bowie faced a difficult night. Here they were with the Mexicans just arriving, and already their command arrangement had broken down. Whether Travis was furious at Bowie or not, this much is

certain: something had gone very wrong with their agreement to act jointly.

Now that the siege had begun, how to patch things up again? How to work out a mutually tolerable arrangement between the touchy, sensitive Travis and the stubborn, independent Bowie? Certainly friction, indecision, and divided responsibility could only lead to disaster.

At this point, events took a turn beyond the power of either man. Bowie, ill for weeks, collapsed completely. Literally overnight he was unable to carry on. In the medical ignorance of the day, some said it was “hasty consumption”; others pneumonia; others typhoid fever; others compromised on something called “typhoid pneumonia.” Almost certainly it was not—as many claimed later—a fall or an accidental blow from a cannonball.

In any case, it immediately solved the command problem. Early in the morning of the 24th Bowie turned his responsibilities over to Travis. Then he had his men take him to a small room in the low barracks. As he was carried off, lying pale and weak on a litter, he called Juana Alsbury to his side: “Sister, do not be afraid. I leave you with Colonel Travis, Colonel Crockett and other friends. They are gentlemen and will treat you kindly.”

With the command at last in the hands of one man, the defenders faced their first day of siege. It was clear from the start that the Mexicans meant business—the warm, cloudy morning found them busy digging a new earthwork on the river bank about 400 yards away. Still out of rifle range … but they were closer than the night before.

Early that afternoon they opened up. First a 5-inch howitzer … then a long 9-pounder … then still another 9-pounder. Shells rained on the Alamo. The garrison occasionally answered, but most of the time saved its fire. Everywhere the

men huddled at their posts, dodging the flying dirt and stones. Almeron Dickinson on the church roof … William Carey at the artillery headquarters in the southwest corner … Crockett and his Tennessee “boys” behind the palisade. Others crouched in the irrigation ditches just outside the walls—an advanced line used for extra protection. In the dark little rooms of the church the women and children waited in uncertainty.

A crash in the corral—the cry of a wounded horse. Another crash on the southwest parapet—the 18-pounder sent spinning. Yet another along the wall—this time a 12-pounder dismounted.

At last, silence. It was dark when the Texans took stock. Incredibly—miraculously—no one killed or even hurt. In the gathering dusk, Travis used the lull to send off Albert Martin with the message “To the People of Texas & all Americans in the world.”

The Mexicans made no attempt to stop him. Only 600 of Sesma’s troops had yet arrived—just enough to cover the south and west. Taken by surprise, they were too far away to counter the move. Besides, they were busy getting organized and in no mood to worry about occasional enemy messengers. There would be plenty of time for that.

As the troops settled down, Santa Anna was everywhere, preoccupied as usual with even the most minor details. At nine o’clock that morning he personally supervised the distribution of shoes. At eleven he was off scouting with a small cavalry unit. By afternoon he was back in town, watching his guns bombard the fort. Local informants—always happy to accommodate either side—offered the good news that four defenders were killed.

That evening His Excellency made a gesture quite in keeping with the sardonic streak that ran deep within him; he

ordered his band to serenade the besieged. To the blare of horns and trumpets, he added the blast of an occasional grenade.

There were other bizarre touches. Men out of gunshot were often within earshot, and insults were freely exchanged. Townspeople wandered between the lines without serious interference. Margarito García, a friendly local Mexican, slipped over to the Alamo after dark and chatted with his friends in the garrison. Estaban Pacheco even brought Captain Seguin his meals.

Later in the evening the festive touch suddenly evaporated. A sharp-eyed Texan spied something moving on the footbridge leading across the river. Shouts of alarm, and a blast of rifle fire caught Colonel Juan Bringas crossing the bridge with five or six men on a scouting mission. One Mexican toppled over dead; the others wildly stampeded back across the bridge. In the commotion Colonel Bringas himself fell into the river, barely managed to reach safety as the bullets cut the water around him.

Not all the Mexican efforts were as futile. In the gray drizzling dawn of February 25 the Alamo men found another enemy earthwork going up by the McMullen house just across the river.

More was to come. At 10

A.M.

a blare of Mexican bugles … a hail of solid shot, grape and canister. Through the smoke the garrison could see little figures swarming across the river; scattering among the adobe huts and wooden shacks south of the main entrance. The defenders held their fire, as the enemy soldiers darted from building to building, always moving closer. Now 200 yards … 100 … 90.

A roar of cannon from the Alamo. Point-blank range, and Artillery Captains Carey and Dickinson made the most of it. Guns blasted from the church roof, the earthwork stockade, the sandbagged main entrance. The Tennessee “boys” joined

in with their squirrel rifles, and David Crockett was everywhere cheering them on. Cavalryman Cleland Simmons, other volunteers, rushed over to lend support. Who wouldn’t want to fight beside Crockett today?

The Mexicans wavered, stopped, dodged behind the ramshackle buildings that covered their advance. A serious problem for the Texans. This area, known locally as La Villita, was a jumble of shacks and huts, offering good shelter and dangerously close to the Alamo. Never a part of San Antonio proper, La Villita grew up in the days of the Spanish—a place where soldiers lived with their common-law wives. It had always remained a disreputable section, happily patronized by whatever garrison was holding the town at the moment.

Little matter its past; today La Villita was a valuable military asset. Protected by its buildings, the Mexicans could plant new batteries in the very shadow of the Alamo. Something had to be done.

The Alamo gate briefly opened. Through the smoke Robert Brown, Charles Despallier, James Rose, several others raced with torches toward the nearest buildings. Smoke poured from the thatched roofs; dry wooden walls crackled in flames. Hard dangerous work, for the enemy might be anywhere. James Rose barely escaped the grasping hands of a Mexican officer.

But the job was done. The nearest huts were burned; the Texans had a new field of fire; the Mexicans lost their best cover.

By noon they had had enough. Sesma’s men pulled back to the river in confusion, dragging their casualties with them. The Texans relaxed, pleased with the morning’s work. Taking stock, Travis discovered that—again miraculously—he had no serious casualties. Only two or three men clipped by flying rocks.

At Mexican headquarters Santa Anna was taking stock too. A definite repulse, but there were compensations. His own losses were also light—only eight casualties. Maybe the men were too cautious, but at least they knew how to take cover. Moreover, he was at last on the Alamo side of the river. Even if the Texans destroyed the buildings nearest the fort, he still held a few good houses close to the water.

To add to the bright side, only 300 Mexicans had made the attack—the Matamoros battalion reinforced by the Jimenez. Things would be different when the rest of the troops reached San Antonio. Where were they anyhow? Santa Anna sent for Colonel Bringas, by now dried out from his midnight swim. Bringas was soon on his way to General Gaona, marching leisurely from the Rio Grande. Gaona was ordered to hurry along his three best companies by forced march.

A hot, muggy afternoon replaced the morning drizzle. The Mexican guns died, the townspeople crawled out from their houses again. Once more noncombatants slipped back and forth across the lines, providing the gossip either side wanted most to hear.

But that evening there was no serenade by Santa Anna’s band. At 9

P.M.

the wind shifted and a norther soon lashed at attacker and defender alike. Still, it was not an idle night for the Mexican Army. Sesma’s rear units had been arriving all day, and finally there were enough troops to start maneuvering in true European fashion.

Colonel Morales led a detachment to dig trenches protecting the hard-won ground in La Villita. Two new batteries were also planted across the river—one about 300 yards south of the Alamo, the other near the powderhouse 1,000 yards to the southeast. The Matamoros battalion moved up to support both. The cavalry occupied the hills to the east and the Gonzales road by the old slaughterhouse—it was now

time to stop that absurd stream of enemy messengers gallivanting over the country.

Travis didn’t let all of this go unchallenged. A hail of grape and rifle fire greeted a Mexican unit testing the Alamo defenses on the north. Later a group of Texans sortied out on the east for a skirmish with some of Sesma’s men. Another squad of defenders raided La Villita to the south. They yanked down a few of the shacks for firewood—always a problem at the Alamo—and burned others to clear the area in front of the new Mexican earthworks.

But it was clear things couldn’t go on this way. The Mexicans were moving closer, drawing the ring tighter all the time. Feeling the pressure, several of the local Mexican defenders slipped out during the night, crossed the lines and gave themselves up. They asked to be taken to Santa Anna, but were coldly told that His Excellency had gone to bed and couldn’t be disturbed until morning.