A Train in Winter (27 page)

Authors: Caroline Moorehead

Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier’s last letter from Romainville, written on 21 January 1943

To her mother, Marie-Claude wrote that she was taking with her a small volume of Rimbaud’s poems, and that she was in very good physical shape, except that she seemed to have had an early menopause, ‘but since this is more practical when travelling, I am not complaining’. Betty’s letter to her parents was equally cheerful. Observing that she had already spent five months in La Santé and five in Romainville, she said that she thought she would be home before another five months were up.

Rumours filled the fort. Betty remembered that, during her many interrogations, she had been told that she was not very likely to be shot, but that what lay in store for her would probably be worse than death. Hélène Bolleau reminded the others of the remark she had overheard in Angoulême prison, when an officer told one of the guards that the Germans had ‘other plans’ for the women. But for the most part the women were excited: even labour in a German factory could not be worse than enforced idleness, uncertainty and too little food in the hands of the Gestapo. Marie-Elisa Nordmann urged Simone Sampaix, whom she had taken under her wing, to dress as warmly as possible for the journey, wearing the sweater and wool jacket that her mother had made for her, as well as an almost new overcoat given to her by one of the other prisoners; and to put on two pairs of woollen socks. They should wear as many layers as possible, the women agreed, in case they were going somewhere very cold. Poupette and Marie Alizon decided to take the fur scarves that they had brought with them from Rennes and clung on to during all the months of captivity.

No one slept much. Last-minute notes were written to families; bags were packed and unpacked. Guards came round bringing a loaf of bread and a 10-centimetre piece of sausage for each of the women, saying that they should make them last because the journey might take several days. On the 23rd, the women were driven to the camp at Compiègne, near the railway station, where eight other women, recently arrested or brought from other prisons, arrived to join them. They spent the night in bunks, in a vast hall.

One of these new eight women was Georgette, Danielle’s organiser in Ivry. She had finally been caught by the Gestapo on 3 January, after a tip-off to the police by her concierge. From Compiègne, Georgette managed to smuggle out a letter to her family. She was, she said, ‘sans linge, vivres et argent’, without clean underclothes, food or money, everything having been taken from her. ‘I leave to your care my Pépée … my little Pierrette… I kiss you with all my heart, our morale is very good… I’ll be back soon’.

The morning of 24 January 1943 was damp and very cold. There were wisps of fog and low clouds. It was a Sunday. Just as it was getting light, the 230 women were taken to the station in lorries, escorted by German soldiers and French policemen, and led across to a siding known as the ‘platform of the deportees’; there they were put on to four empty cattle trucks. On the way to the station they had shouted out to the few people already about; but these had looked away and hurried past. The front carriages of the train, already closed, contained 1,446 men, put on board the night before; among them was Georges Grünenberger, Simone’s friend from the Battalions de la Jeunesse. Between sixty and seventy women were directed to each of the first three cattle trucks; that left twenty-seven for the fourth, into which Charlotte, Danielle, Marie-Claude, Betty, Simone and Cécile climbed. Each contained half a bale of straw, which reminded Charlotte of a barn that needed sweeping. There was a barrel to serve as lavatory. What Madeleine Normand did not know—and would never learn—was that just as they were leaving Compiègne, her mother, sick with anxiety about her daughter, was dying.

The doors were closed and bolted. In the fuller carriages it was impossible for all the women to stretch out at the same time, so a rota was established, with half of them lying and half sitting, at any one time. Suitcases were piled up around the barrels, to stop them tipping over when the train began to move. In Charlotte’s carriage, Jakoba van der Lee, a Dutch woman in her early fifties, who had once been married to an Arab sheikh, placed her black hat on top of her suitcase, unfolded her blanket and wrapped her magnificent otter coat around her legs. Of all the women on the train, the reason for her presence was perhaps the most absurd: she had written a letter to her brother in Holland, wistfully predicting Hitler’s defeat. It had been intercepted by the Germans.

Before leaving, urged on by Marie-Elisa, who thought it important to record and remember the identity of each and every woman on the train, efforts had been made to establish names, ages, number of children and any small important facts about each one’s story.

Of the 230, 119 were communists. Nine were not French. The majority came from every part and region of France, from Paris, Bordeaux, Brittany, Normandy, Aquitaine and along the banks of the Loire. They had sheltered resisters, written and copied out anti-German pamphlets, hidden weapons in shopping bags, helped carry out acts of sabotage. Twelve, of whom Raymonde Sergent was one, had been

passeurs

, guiding people across the demarcation line. Thirty-seven came from the Pican–Dallidet–Politzer

affaire

, seventeen from Tintelin’s printers and technicians; forty had been active in and around Charente, Charente-Maritime and the Gironde. Some two dozen of the women on board—like Mme van der Lee—had had almost nothing to do with the Resistance, beyond making ill-judged remarks about the occupiers or having connections to resisters. There were the three

délatrices

, informers, their presence on board all the more peculiar in that they had supported, rather than opposed, the occupiers.

There was one doctor on the train, Adelaïde Hautval, one dentist, Danielle, and a midwife, Maï, and four chemists, of whom Marie-Elisa was one. There were farmers, shopkeepers, women who had worked in factories and in the post office, teachers, and secretaries. Twenty-one were dressmakers or seamstresses. A handful were students. One was a singer. Forty-two described themselves as housewives. Just over half were married and fifty-one had had their husband or lover shot by the Germans. Ninety-nine had between them 167 children, of whom the youngest was a baby of a few months. Marguerite Richier, a widow in her sixties, had given birth to seven children; two of her daughters, Odette and Armande, were on the train with her.

Of great importance, for what was about to happen to the women, was the fact that there were fifty-four who were aged 44 and over, though most were in their late twenties and early thirties. The youngest girl on the train was Rosa Floch, who had just celebrated her 17th birthday. The eldest was a 67-year-old widow from Chalôns-sur-Seine, Marie Chaux, denounced for keeping her son’s revolver, a memento of the First World War, in her kitchen drawer; though it was later discovered that she had also provided a safe house for resisters.

On board were also a number of families. Lulu and Carmen, Yolande and Aurore, were only two of several pairs of sisters; and there were six mothers and daughters, among them Emma and Hélène Bolleau, who had desperately tried but failed to be allowed to travel together in the same cattle truck. The entire Brabander family were on the train, the men in the front carriages, Hélène and Sophie at the back. The previous day, Dr Brabander, catching sight of his wife and daughter at Compiègne, had begged to be allowed to speak to them. Permission was refused. And there was Aimée Doridat and her sister-in-law Olga Godefroy, members of an extended family of communists from Nancy. Aimée was another woman who might have escaped, having been warned by a railway worker, using her eight-year-old son as messenger, that she would do well to go into hiding; but she did not want to leave her six brothers, all of whom had also been detained.

But most important of all was the fact that the women, despite differences of age, background, education and wealth, were friends. They had spent the months in Romainville very close together and it was as a train full of friends, who knew each other’s strengths and frailties, who had kept each other company at moments of terrible anguish, and who had fallen into a pattern of looking after each other, that they set out for the unknown. Adelaïde, assuming that they were bound for a German factory, wondered how they would all manage, working together, mindful of one another.

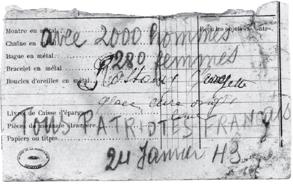

One of the notes slipped through on to the tracks as the train crossed France

As the train pulled out of Compiègne, the women took pencils and scraps of paper out of their bags and began to write notes. Viva ended hers ‘I will return’, underlining the words. On one side they gave the names and addresses of their families and wrote that they were on a train, bound for some distant place, which they suspected would be Germany. Using nail files to gouge out knots in the wood of the carriage walls, they waited for the train to pause at a station before pushing the notes out, with a little money and a request that anyone who found them should send them on to their families. ‘Look after Claude,’ wrote Annette Epaud to her family. And to her son: ‘Maman t’embrasse, mon cher fils.’ She had packed among her few things Claude’s photograph and the little portrait of him done in Romainville. There was some talk of trying to escape from the train, but the doors were bolted on the outside.

Annette Epaud with her husband and son Claude

The drawing of Claude done in Romainville which Annette kept always by her

As the first day wore on, the women took it in turns to keep watch at the holes, trying to make out the names of the places they passed through. At Chalôns-sur-Marne, where the train stopped, a railway worker walked along the side of the carriages, whispering, ‘They’re being defeated. They’re losing Stalingrad. You’ll be back soon. Be strong, girls.’ At Metz, the French train driver was replaced by a German; it was the Gestapo who were now in charge. When a few of the women were allowed out to collect water for the others, a station guard told them, ‘Make the most of it. You’re going to a camp from which you’ll never return.’ His ominous words meant nothing to them. The women sang, songs remembered from their childhood, to keep cheerful.