A Writer at War (21 page)

Authors: Vasily Grossman

Soldiers with letters from home sent folded in a triangle and a copy of

Krasnaya Zvezda,

bottom right.

Stalingrad is burned down. I would have to write too much if I wanted to describe it. Stalingrad is burned down. Stalingrad is in ashes. It is dead. People are in basements. Everything is burned out. The hot walls of the buildings are like the bodies of people who have died in the terrible heat and haven’t gone cold yet.

Huge buildings, memorials, public gardens. Signs: ‘Cross here.’ Heaps of wires, a cat sleeping on a window sill, flowers and grass

in flowerpots. A wooden pavilion where they sold fizzy water is standing, miraculously intact among thousands of huge stone buildings burned and half destroyed. It is like Pompeii, seized by disaster on a day when everything was flourishing. Trams and cars with no glass in their windows. Burned-out houses with memorial plaques: ‘I.V. Stalin spoke here in 1919.’

11

Building of a children’s hospital with a gypsum bird on the roof. One wing is broken off, the other stretched out to fly. The Palace of Culture: the building is black, velvety from fire, and two snow-white nude statues stand out against this black background.

There are children wandering about, there are many laughing faces. Many people are half insane.

Sunset over a square. A terrifying and strange beauty: the light pink sky is looking through thousands and thousands of empty windows and roofs. A huge poster painted in vulgar colours: ‘The radiant way.’

A feeling of calm. The city has died after much suffering and looks like the face of a dead man who was suffering from a lethal disease and finally has found eternal peace. Bombing again, bombing of the dead city.

Although most of the men had been called up and were serving outside the city, the civilian population of Stalingrad had been swollen by refugees from the Don steppe. Grossman tried to interview some of them, including an old woman and a younger one called Rubtseva from a collective farm.

‘Where is your husband?’

‘No, don’t ask,’ whispers Seryozha, her boy. ‘You’ll upset Mama.’

‘He’s done his share of the fighting,’ she replies. ‘He was killed in February.’ She had received the notice. Her story about Red Army cowards: ‘A German [plane] was diving like a spear. Just the right moment to shoot him, but all our “heroes” were lying hidden in the tall weeds. I shouted at them: “Ah, you bastards!”

‘Once, some soldiers were escorting a [German] prisoner through the village. I asked him: “When did you join the fighting?” “In January,” he answered. “Then it was you who killed my husband.”

The Palace of Culture in Stalingrad, described by Grossman.

I raised my arm, but the guard didn’t let me hit him. “Come on,” I said, “let me hit him.” And the escort replied: “There’s no such law [to permit it].” “Let me hit him without any law, and I’ll go away.” He wouldn’t.

‘Of course, one could live under the Germans, but it wasn’t the life for me. My husband has been killed. Now all I’ve got left is Seryozha. He’ll become a big person under the Soviets. Under the Germans he’d die a shepherd.

‘The wounded men stole so much from us, we couldn’t stand it any longer. They dug up all our potatoes, cleaned out all our tomatoes and pumpkins. Now we’ll have to live through a hungry winter. They are cleaning out our homes too – shawls, towels, blankets. They’ve slaughtered a goat, but one feels sorry for them just the same. If a wounded man comes to you and he’s in tears, you’ll give him your supper and you start crying yourself.’

The old woman: ‘These fools have allowed [the enemy] to reach the heart of the country, the Volga. They’ve given them half of Russia. It is true, of course, that the [Germans] have got a lot of machines.’

Grossman, when visiting the Traktorny, the great tractor works in northern Stalingrad, heard about the attack of the 16th Panzer Division on 23 August from the confusingly named Lieutenant Colonel German commanding the anti-aircraft regiment.

On the night of the 23rd, eighty German tanks advanced on the Traktorny in two columns, and there were a lot of vehicles with infantry. There are many girls in German’s regiment, instrument operators, direction finders, intelligence, and so on. There was a massive air raid at the same time as the tanks came. Some of the batteries were firing at the tanks, others at the aircraft. When the tanks had advanced right to the battery of Senior Lieutenant Skakun, he opened fire at the tanks. His battery was then attacked by aircraft. He ordered two guns to fire at the tanks, and the other two at the aircraft. There was no communication with the battery. ‘Well, they must have been knocked out,’ [the regimental commander] thought. Then he heard a thunder of fire. Then silence again. ‘Well, they are finished now!’ he thought again. Firing broke out again. It was only on the night of 24 August that four soldiers [from this battery] came back. They had carried back Skakun on a groundsheet. He had been heavily wounded. The girls had died by their guns.

Golfman’s battery was fighting for two days using [captured] German weaponry: ‘What are you, infantry or artillery?’

‘We are both.’

Both sides were using captured weapons and vehicles, which caused great confusion.

A light tank brigade commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Gorelik was having a break in the area of the tractor plant when some tanks broke suddenly into the area. ‘Germans!’

‘Germans?’ The lead tank in the German column was one of our KVs.

12

One anti-aircraft subunit had been ordered to retreat, but as they were unable to remove their guns, many of them stayed. Their commander, Lieutenant Trukhanov, took over from the gun-layer and was firing at point-blank range. He had hit a tank and then was killed himself.

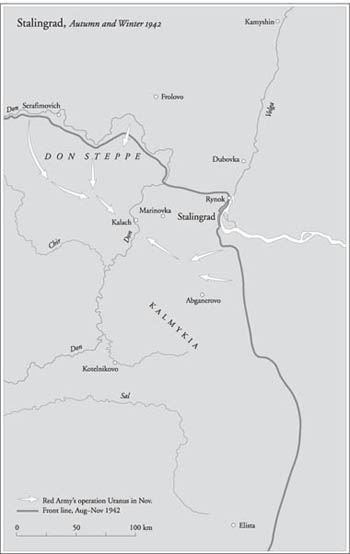

Stalingrad, Autumn and Winter 1942

With Gorelik’s brigade. People don’t realise the importance of the events of 23 August. But they are offended by the lack of attention. No medals have been awarded. And the staff car has been taken away from the brigade commander who is down with typhoid fever.

Sarkisyan. He didn’t go to Stalingrad on Sunday, because he knew a woman in the village, and he found out that beer was going to be delivered there. He had jammed himself in the machine of the German military scheme like a simple piece of metal. Perhaps, he caused Hitler insomnia for several days: they hadn’t managed to keep up the momentum! And speed is almost the most important thing of all.

Grossman is presumably referring to the battle fought on 23 and 24 August by Captain Sarkisyan and other anti-aircraft gun crews also operated by young women, many of them Stalingrad high school students. Demonstrating an astonishing courage, they held up the 16th Panzer Division until all thirty-seven emplacements were destroyed by tank fire. Sarkisyan, like Colonel German, recounted the battle to Grossman, emphasising that ‘the girls refused to go down into their bunkers’, and fought the panzers head-on. But the real problem facing General von Wietersheim’s XIV Panzer Corps was a lack of fuel.

Using a combination of his own observations and the remarks of those he interviewed, Grossman later wrote an imaginative description of the retreat late in August from the Don to the Volga when headquarters groups from the retreating 62nd and 64th Armies reached Stalingrad.

Those were hard and dreadful days

. . . The armies were retreating. Men’s faces were gloomy. Dust covered their clothes and weapons, dust fell on the barrels of guns, on the canvas covering the boxes full of headquarters documents, on the black shiny covers of staff typewriters, and on the suitcases, sacks and rifles piled chaotically on the carts. The dry, grey dust got into people’s nostrils and throats. It made one’s lips dry and cracked.

That was a terrible dust, the dust of retreat. It ate up the men’s faith, it extinguished the warmth of people’s hearts, it stood in a

murky cloud in front of the eyes of gun crews. There were minutes when people forgot their duty, their strength and their weapons, and a murky feeling would come over them. German tanks were moving on the roads with a rumbling noise. German dive-bombers were hanging over the Don crossings by day and by night. ‘Messers’ were whistling over the supply carts. Smoke, fire, dust, terrible heat. On those days, the faces of the marching soldiers were as pale as those of the wounded men lying on the shaking one-and-a-half-ton trucks. On those days, men marching with their weapons felt like moaning and complaining, just like those who lay on the straw in villages, their bandages bloodstained, waiting for the ambulances to pick them up. The great nation’s great army was retreating.

The first units of the retreating army entered Stalingrad. Trucks with grey-faced wounded men, front vehicles with crumpled wings, with holes from bullets and shells, the staff Emkas with star-like cracks on the windscreens, vehicles with shreds of hay and tall weeds hanging from them, vehicles covered with dust and mud, passed through the elegant streets of the city, past the shining windows of shops, past kiosks painted light blue and selling fizzy water with syrup, past bookshops and toyshops. And the war’s breath entered the city and scorched it.

One has to be honest. On those anxiety-filled days, when the thunder of fighting could be heard in the suburbs of Stalingrad, when at night one could see rockets shot far away into the sky, and pale blue rays of searchlights roamed the sky, when the first trucks, disfigured by shrapnel, carrying the wounded and the belongings of retreating headquarters appeared in the streets of the city, when front-page articles announced the mortal danger for the country, fear found its way into a lot of hearts, and many eyes looked across the Volga. It seemed to these people that they didn’t have to defend the Volga, that it was the Volga that had to defend them. These people were saying a lot about the evacuation of the city, about transport, about steamers going to Saratov and Astrakhan; it seemed to them that they cared for the city’s fate, while in fact, unwillingly, they made the city’s defence more difficult by silently indicating, with their fears and anxiety, that Stalingrad had to be surrendered.

1

Tolstoy, Aleksei Nikolaevich (1882–1945), novelist and playwright, a cousin of Leo Tolstoy, but estranged from the rest of the family. He embraced revolutionary politics before the First World War, yet returned to the Soviet Union only in 1923 when flattered and reassured by the new Bolshevik authorities. His major work was the epic

Peter I

, yet he also wrote science fiction. The survival of his career was assured in 1938 during the Great Terror with his grovelling novel

Khleb

, praising Stalin’s defence during the civil war of Tsaritsyn, later renamed Stalingrad. During the war he wrote

Ivan Grozny

in two parts, as well as the sort of ‘patriotic articles’ described here.

2

German pidgin-Russian meaning: ‘Rus, hands up!’

3

There is an unexplained topological phenomenon in which the great rivers of Russia flowing southwards, especially the Volga and the Don, tend to have very high western banks and flat eastern banks.

4

Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, a sixteen-year-old Moscow student, served behind German lines in the province of Tambov with a partisan group and used the nom de guerre of ‘Tanya’. She was caught by the Germans, tortured and executed in the village of Petrishchevo on 29 November 1941. Before the Germans hanged her in the village street, she is said to have cried out: ‘You’ll never hang us all. My comrades will avenge me.’ She was awarded posthumously the medal of Hero of the Soviet Union. In more recent years, the story of her heroism has been rather undermined by accounts from local people who blamed her for setting fire to houses, part of Stalin’s ruthless order to destroy all shelter so that Germans froze to death, even though probably far more Russian civilians suffered.

5

They are bewailing the fact that there will be four children deprived of her milk.

6

This was west of Kamyshin on the Volga, two hundred kilometres by road north of Stalingrad.

7

General (later Marshal) Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov (1896–1974), a cavalry sergeant in the First World War, he was wounded in Tsaritsyn (later Stalingrad) in 1919. In 1939, he won the battle of Khalkin-Gol against the Japanese in the Far East. In 1941, Zhukov was made responsible for the defence of Leningrad and he then masterminded the battle of Moscow.