A Writer at War (37 page)

Authors: Vasily Grossman

Grossman’s ‘ruthless truth of war’ did not necessarily make things easy for his editor at

Krasnaya Zvezda

, but Ortenberg certainly respected him, as his own comments show. ‘

Grossman remained true

to himself. In Stalingrad, Vasily Semyonovich used to spend days and nights with the main characters of his articles, in the very heat of the fighting. He did

the same here at the Kursk salient. The following lines are a proof of this: “I happened to visit the units that received the hardest blow from the enemy . . .” “We were lying in a gully listening to the fire from our guns and explosions of German shells . . .” He had seen the wounded and killed Soviet soldiers. He thought it disgraceful to write nothing about them. With great difficulties, we managed to get the following truthful lines from his essay published: “The battery commander, Ketselman, was wounded. He was dying in a pool of dark blood . . .”’ Soviet censorship wanted to suppress such harsh images, but in this case at least, Ortenberg managed to persuade them to leave Grossman’s work untouched. This was the piece in question:

There wasn’t anyone in the whole world

at that moment who deserved rest more than these Red Army soldiers sleeping among puddles of rainwater. This gully, where the ground and leaves were trembling from shots and explosions, was to them like a most remote rear area, like Sverdlovsk or Alma-Ata. The sky which was filled with sparkles and white clouds from the fire of anti-aircraft guns, the sky in which twenty-six German dive-bombers banked and dropped into a dive to attack a railway station, was a cloudless, peaceful sky. Here they were, sleeping on the wet grass, among flowers and soft, furry burdock leaves . . .

An officer, whose flank the brigade was covering, had retreated, allowing the brigade to withdraw. But the brigade commander, who could clearly see the consequences of withdrawal, answered: ‘We won’t retreat, we’ll stay here to die!’ And he was permitted to do that.

At dawn, German tanks started to attack. [Enemy] aircraft attacked at the same time and set the village on fire . . .

Battery commander Ketselman was wounded. He was dying in a puddle of black blood; the first artillery piece was broken. A direct hit had torn off an arm and the head of a gun-layer. Senior Corporal Melekhin, the gun commander, the cheerful, quick virtuoso of this death struggle in which tenths of seconds sometimes determine the outcome of a duel, was lying on the ground with heavy shell-shock, looking at the cannon, his stare heavy and murky. The gun was reminiscent of a ragged, long-suffering man. Strips of rubber were hanging from the wheels, torn by the explosions . . .

Only the amunition bearer, Davydov, was still on his feet. And Germans had already come very close. They were ‘seizing the barrels’, as artillerists say. Then the commander of the neighbouring gun, Mikhail Vasiliev, took control. These were his words: ‘Men, it isn’t a shame to die. Even cleverer heads than ours sometimes happen to die.’ And he ordered them to open fire at the German infantry with canister. Then, having run out of anti-personnel rounds, they began to fire at the German sub-machine-gunners at point-blank range with armour-piercing shells. That was a terrible sight.

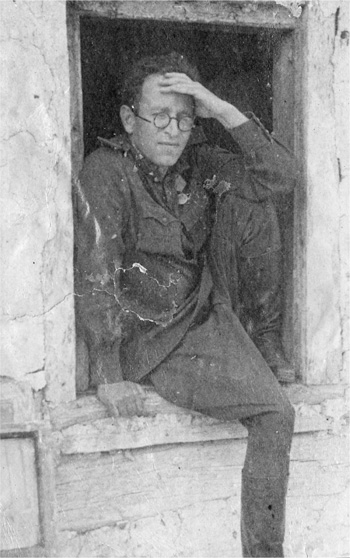

Grossman and Baklanov (centre). Celebration with the 13th Guards Rifle Division.

Grossman also caught up with the 13th Guards Rifle Division, which had been commanded at Stalingrad by General Rodimtsev. He took the opportunity to interview its new commander about the fighting.

A meeting with Rodimtsev’s 13th Guards Division at the Kursk salient. It is now commanded by General Baklanov, a young man who started the war as a captain. He had been an athlete in Moscow.

‘

Sovinformburo

has been writing ever since the war began that “German pillboxes have been destroyed”, but I’ve never seen a single German pillbox. They’ve only got trenches. The men are

now fighting intelligently, without frenzy. They fight as if they were working.

‘Our weaknesses show up in the offensive. Reinforcement units get moved to new locations. They don’t have time to get used to the situation. Some commanders don’t know their calibres and the range of their artillery fire. They don’t know the established quantity of mines per kilometre, the established quantity of wire per kilometre, the rate of fire to suppress enemy defences. “Some fire needed, over there!”’ and he waves his hand.

‘Sometimes regimental commanders give false reports during battles. I usually go out two hours before an attack to check communications, yet the regimental commander goes to his command post ten minutes before the attack and then reports to me: “Everything is ready, I know everything.” The danger of arrogance, of conceit is great.

‘There are many commanders who don’t care about their soldiers’ food and everyday life, they don’t try to study the soldier’s soul. Commanders are sometimes very harsh, but during breaks [in the fighting] they don’t go to their men, talk to them and ask questions. Often this is because commanders are too young. It is sometimes the case that a [junior officer] has soldiers who have sons older than he is.

‘[The cry of] “Forward, forward!” is either the result of stupidity, or of fear of one’s seniors. That’s why so much blood is being shed.’

Grossman found once again, even after all the improvements effected during the course of the previous year, that units continued to suffer from the inability of Red Army commanders and staff officers to think things through.

Colonel Vavilov, Deputy Divisional Commander on Political Work. ‘We were put on alert at midnight on [8/9] July. The order was to have regiments formed up by dawn. We started moving on the 9th during the day. That day was terribly hot. Seventy men went down with sunstroke in one regiment. We were carrying machine guns, mortars, ammunition. During the night of the 9th we had three hours of rest. We arrived in the area of Oboyan, began to organise defensive positions and dug in. And then the order came at once, to carry on another twenty-five kilometres. At dawn on the 12th, we came to the start point, and at once entered the fighting, with two regiments. And didn’t General Zhukov say: “It is better not to begrudge a retreat of five to six kilometres than to send tired men, with no ammunition, into battle!”’

Grossman beside one of the German Tiger tanks destroyed at Kursk.

On the other hand, Grossman was the first to acknowledge that some things had definitely improved.

From the point of view of artillery

, the Kursk operation is more sophisticated than the Stalingrad one. In Stalingrad, the beast was beaten in its lair. In Kursk, the artillery shield resisted the enemy’s attack and the artillery sword started crushing them during the [counter-attack].

8

Grossman also interviewed some pilots from a regiment of Shturmovik fighter-bombers engaged on ground-attack operations, mainly against tanks.

9

Shturmovik regiments claimed the virtual annihilation of the 3rd,

9th and 17th Panzer Divisions during the battle. The Shturmoviks were often flying at less than twenty metres off the ground, as their pilots liked to boast, but their casualties were very heavy.

Shalygin, Nikolai Vladimirovich, [from] Saratov, major in a Shturmovik regiment: ‘Aleksukhin was flying at very low level, attacking vehicles, in fact so low that he returned with the tips of his propeller bent. I made a dive and saw tanks in the barley. The shape of their turret gives them away.

‘Pilot Yuryev came back with blood streaming down his face. “May I report?” He reported and collapsed unconscious. The gunner-signaller had climbed out first, with blood all over him.

‘This excitement of a hunter, I feel as if I were a hawk, not a man. And one does not think about humanity. No, there are no such thoughts. We clear the way. It’s good when the way is clear and everything is on fire.’

The way was about to be made even clearer for the Soviet general offensive. This developed out of the counter-attack at Prokhorovka on 12 July. Operation Kutuzov, launched on the same day on the northern flank, was aimed against the German occupied territory between the Kursk salient and the city of Orel. The Germans had not expected such a rapid reaction. For Grossman, this was a moment of fierce joy. He had a bitter memory of the German capture of the city in the autumn of 1941.

Ortenberg, remembering what Grossman had been through at the time, made sure that he was the correspondent who covered the liberation of Orel. ‘

I must say that I had never forgotten

this episode. And on the July days when we had no doubts that Orel would be liberated, I said to Grossman: “Vasily Semyonovich! Orel is your trauma. I would like you to be there on the day of its liberation. So that you can remember the day when you left it.” Grossman was in Orel on the day of its liberation and wrote an essay about the frightening, tragic days and hours [of its fall to the Germans in 1941] . . . When I read this essay, I understood what Grossman had gone through during those October days of 1941. I met him a year after the battle of Kursk, when I was already at the front.

10

During our conversation I reminded him of the unhappy

episode and let him understand that I felt guilty about it. He smiled and said with sincerity: “I was not angry with you.” And he added: “There was no time for it.”’

We reached Orel on the afternoon

of 5 August by the Moscow highway. We had driven through the cheerful and businesslike Tula, past Plavsk, Chern, and the further we went, the fresher appeared the wounds that the Germans had inflicted on our land.

In Mtsensk, grass was growing in the ruins of houses, the blue sky was looking through the empty eye sockets of windows and torn-off roofs. Almost all villages between Mtsensk and Orel were burned. The ruins of

izbas

were still smoking. Old people and children were rummaging in the piles of brick looking for the surviving household objects: cast-iron pots, frying pans, metal beds disfigured by fire, sewing machines. How bitter and familiar this sight was!

There was a freshly adzed white board with the word ‘Orel’ nailed up by the railway crossing . . . The smell of burning was hanging in the air, a light blue milky smoke was rising from the dwindling fires . . .

A loud-speaker unit was playing ‘The Internationale’ in the square. Posters and appeals were being glued to the walls, leaflets were being handed out to the population. Red-cheeked girls, traffic controllers, were standing at all the crossroads, smartly waving their red and green little flags. A day or two would pass, and Orel would start coming back to life, to work and to studying . . .

I remembered the Orel which I had seen exactly twenty-two months ago, on that October day of 1941 when German tanks broke into it from the Kromsk highway. I remembered my last night in Orel, the ill, terrible night, the humming of fleeing vehicles, the weeping of women running after the retreating troops, the sorrowful faces of people, and the questions that they were asking me, full of anxiety and suffering. I remembered Orel’s last morning, when it seemed as if the whole city was crying and rushing about, seized with a terrible panic. The city was then still in its full beauty, without a single window broken, but it gave the impression of being doomed, of having been sentenced to death . . .

And listening to the speech of a tank colonel, who was standing on top of a dusty tank overlooking the bodies of soldiers and officers

killed in the battle for Orel, hearing his simple, abrupt words of goodbye echoing in the burned-out houses, I understood. This meeting today and that bitter parting on the October morning of 1941 are inseparably linked with one another.