Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (26 page)

Read Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation Online

Authors: Mark Pelling

Tags: #Development Studies

In a network, where difference is positive because it enables exchange, exclusion is more likely to arise externally. In the workshop, there were several references to communication initiatives by the group in the UK that had not fared well.

It should not be assumed that trust is an unalloyed asset, and exclusion a constraint on adaptive capacity, or vice-versa. While it is certainly true that the learning culture within Grasshoppers had arisen through close ties of trust, it clearly also depended on exclusion. After all, potential members who could not cope with the group culture were expected to leave. Similarly, while exclusion enabled trust and learning, the question is what opportunities for learning and for wider social equality are being passed up in the name of maintaining group cohesion?

During the workshop, the group was optimistic about their ability to adapt to the challenges of climate change and variability, as and when needed. When pressed about this confidence, they ascribed it to successful change in the past: ‘Having initiated change, it wouldn’t bother us to change again in whatever direction, if it made sense.’

The adaptive capacity of Grasshoppers seems to be founded in a learning culture. The group fostered learning amongst its members, and this brought significant rewards for the effort of remaining an active member:

Discussion groups are the best way of learning – you can get to know each other’s businesses, better than a lecture theatre.

It’s like 20 heads learning at once, and sharing that information back. It would have taken me a lot longer to get where we are today.

The learning culture resulted in and was supported by a set of learning practices on the part of individual members, reinforced by the group’s values. These had already built a culture of resilient adaptation to climate change:

We measure ground temperature and climate a lot more than other farmers. When we see change we change our practices. The data we have seen is getting warmer. The response to this is to withdraw fertilizer and put cattle out earlier.

A notable feature of the culture of Grasshoppers was the willingness of members to change embedded practices to achieve important life objectives, even to leave dairy farming. This seems a strong contrast with many other farmers who feel stuck, unable to make or even see the changes they need to remain viable. This also suggests that success in applying adaptation as resilience provides confidence for transitional and potentially transformational forms of adaptation at the level of individual businesses.

The members of the group were happy to view the Grasshoppers organisation as something transitory. The formal organisational structure was useful for the moment, but not necessary of itself. Seen as more important, and likely more enduring, were the informal relationships that group membership had fostered. This suggests that the shadow relationships that thicken the social ties within Grasshoppers now also prove a flexible social resource for forming new coalitions as future climate change and other challenges arise. While canonical organisation provides structure to help resolve defined adaptation challenges, shadow systems are the raw resource that should be strengthened to provide capacity to adapt to future uncertain threats and opportunities of climate change. That shadow systems are developed around and as a response to canonical organisation suggests a symbiotic relationship. This also points to a policy opportunity where shadow systems of relevance to wider society can be fostered through canonical organisations.

These two organisational case studies both show the idealised nature of resilience as a form of adaptation. Over time and faced with new challenges, policy directives or sources of information organisations are in a constant process of reinvention. Those that are not will likely not survive long in the everyday cut and thrust of market and political life. Given this reality there is a danger that rather than organisations being tools for protecting valued functions they strive to

maintain their own longevity: resilience being transferred from function to form. Neither organisation studied here fell into this trap; members of Grasshoppers in particular observed that they valued the social bonds made through the group more than the group itself and that these were a resource should future challenges require new coalitions and communities of practice be formed. The close ties of trust in Grasshoppers also provided a key quality control mechanism that was less easy to observe functioning in the shadow system of the Environment Agency. In the latter case new ideas succeeded better with external validation – through academic papers, for example. The need for accountability and measured decision-making in public sector bodies is a particular challenge to those who would argue for embracing the shadow system to build adaptive capacity.

Respondents in both groups described their social relations in terms of communities and networks. Communities provide a powerful focus of social identity, but without the linking function provided by networks they risked becoming isolated from the broad pool of human learning. Networks, on the other hand, can be too diffuse, failing to provide an adequate basis for organised action, except in circumstances where the need to do so overrides the transaction costs involved in negotiating different interests.

The empirical observations made in this chapter support arguments from adaptive management for the contribution of relational qualities such as trust, learning and information exchange in processes of building adaptive capacity. They also caution that social networks or communities of practice will always exclude some actors and ideas and should not be seen as a panacea. For organisational management concerned with adapting to climate change four questions are raised by this research:

• Can the informal social relationships of the shadow system be embraced inside public sector organisations or are potential conflicts with the need for efficiency, transparency and vertical accountability intolerable?

• To what extent can investments in local formal organisations, like Grasshoppers, foster and maintain independent but linked shadow systems providing a secondary local social resource for climate change adaptation?

• To what extent might contingency planning to manage climate change risk compromise or complement efforts to build adaptive capacity to manage uncertainty?

• What management, training and communication tools exist to facilitate the building and maintaining of constructive social capital and social learning within and between organisations?

Modifying formal institutions to support motivated professionals in developing informal social ties and expand their membership of communities of practice to cross epistemic divides is one way of addressing this final challenge. At a larger scale investment in boundary organisations and individuals will help thicken the social resource for adaptation, and better cope not only with the direct impacts of climate change but the more dynamic organisation landscape that may well be an outcome of the economic as well as environmental instability associated with climate change. Scope for adapting governance regimes through transitional and transformational change is the focus of the next two chapters.

Adaptation as urban risk discourse and governance

In Cancun the most common idea is that ‘it is not my problem, if things go bad, I can flee to another state’.

(Ex-member of the Quintana Roo State Congress)

The population mobility that enables and characterises rapid urbanisation has consequences also for discourses of responsibility, and finally the willingness and capacity of officials and those at risk to take action and reduce exposure and susceptibility to climate-change-associated hazards in a specific place. Mobile urban populations and the dynamic economies and social systems they are part of present both a context for climate change adaptation and, through the inequalities they generate, a target for transitional and transformational reform.

This chapter uses urban cases because the social and political concentration of urbanisation brings to the surface competing visions and practices of development. But the key argument of this chapter – that as discourses of adaptation begin to emerge worldwide they can either challenge or further entrench development inequalities and failures – is applicable across all development sectors.

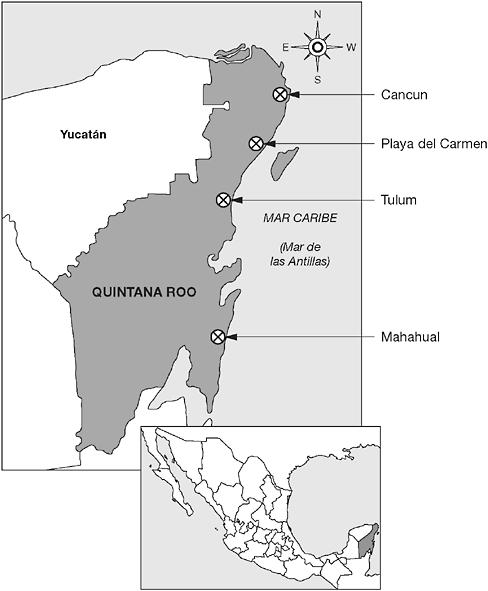

Evidence for the interaction of adaptation with development norms and practice is presented from four rapidly expanding, but contrasting, urban centres in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo: Cancun (population in 2008 approximately 1.3 million), Playa del Carmen (100,000), Tulum (5,000) and Mahahual (1,000) (see

Figure 7.1

).

Quintana Roo is amongst the most rapidly urbanising places worldwide. Urbanisation is driven by state-sponsored and globally-financed international tourism in an area exposed to hurricanes and temperature extremes. National policy to exploit the environment of Quintana Roo for tourism attracts over 2 million tourists a year alongside large numbers of labour migrants from neighbouring states as well as international capital, and so generates risk to climate-change-associated hurricane hazards and more indirect impacts of climate change on the global economy and subsequent tourist numbers. As capital investment in tourism increases so the environmental attractor for tourists has changed from reef diving to beach tourism and now golf course condominiums. At each stage capital has inserted itself ever more forcefully between nature and its consumer. In so doing capital has generated and extracted greater financial returns while

Figure 7.1

Quintana Roo and study sites

(Source: adapted from Cuéntame … de México, 2009)

alienating the consumer from her ecological foundations. The process has shifted economic reliance from a natural to an increasingly artificial ‘second nature’ (Smith, 1984). The result is a bifurcation in development strategies between those that exploit residual ‘natural’ spaces and the growing, capital intensive exploitation of second nature with greater environmental and social external costs as well as wealth generating potential. Capital insertion and the imposition of a second nature have occurred at different paces and can be found existing to

varying degrees along the Caribbean coast. Cancun is the most intensive, with Playa del Carmen also presenting a mature capitalised urban system. Mahahual and Tulum are small urban centres at the brink of rapid capitalisation. The focus of this study is to explore the character of civil society within each urban form and so to examine the ways in which the urban process has given shape to and been influenced by this aspect of governance with a view to applying this knowledge to assess capacity to cope with current and adapt to future climate change impacts.

Layered on top of the impacts of capitalisation on the root causes of vulnerability and adaptive capacity is a more superficial but nonetheless important policy realm of hurricane risk management. This is the most tangible expression of hazard liable to be influenced by climate change on the coast. Records for hurricane activity in Quintana Roo begin in 1922 with a category one event (149 kilometres per hour). The first category four event was Charlie in 1951 (212 kilometres per hour), and it has been followed with increasing regularity by four additional category four hurricanes, and Gilbert (1988) and Dean (2007) both making landfall as category five hurricanes. These events reveal underlying vulnerabilities. Hurricane risk management succeeds well in compensating for proximate causes of vulnerability through evacuation of those at risk. But discourse around risk stops here, masking underlying root cause drivers of risk and unsustainable development.

This chapter contrasts with the empirical analysis of organisational adaptation presented in

Chapter 4

both in terms of the scale of analysis but also the analytical lens. This shifts from one that stays close to the systems-based analysis of social learning and self-organisation to one that deploys aspects of discourse analysis and regime theory to help emphasise the political and value rich contexts that, alongside capacity for self-organisation, help determine innovation and dissemination of new ideas from the base and how far these might re-shape local governance regimes for adaptation and development in these sites. Different actors are shown to hold contrasting and sometimes conflicting visions of development that in turn lead to preferences for resilience, transition or transformation in society when faced with climate change. Following this introduction a short contextual section provides geographical and methodological background to the study. Each settlement is then analysed using a common framework with a concluding discussion drawing out contrasting relations between adaptation and development in each case.