After Tamerlane (23 page)

Authors: John Darwin

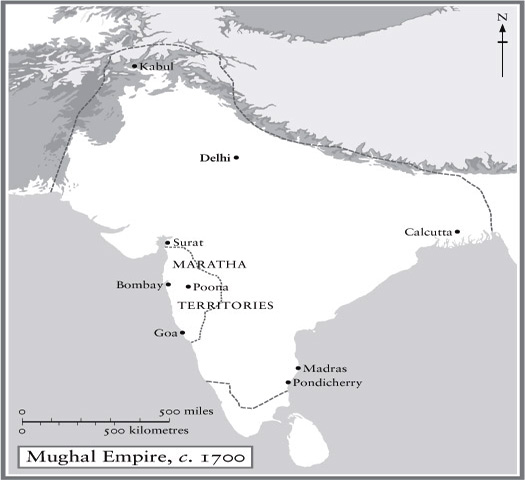

India's openness to commerce and culture from Iran and Central Asia, and to seaborne influence along its vast peninsular coastline, when combined with the rugged impenetrability of the Deccan, may be the key to the failure of any single ruling power â even one as skilful and sophisticated as the Mughals â to unify South Asia and impose the cultural and administrative uniformity achieved by the Ming in China. Muslim elites dominated the main states in the south after the fall of Hindu Vijayanagar in 1565. But the struggle to subordinate the Hindu gentry of the Deccan and to impose the Mughal system of land grants in exchange for administrative and military service provoked a gathering revolt centred on the Maratha region around Satara and Poona. It was led by Sivaji, a Hindu soldier of fortune â a man of âmeane stature⦠of an excellent proportion⦠distrustful, seacret, subtile, cruel, perfidious' in the judgement of an English observer, the Revd John L'Escaliot.

147

In 1674 the English East India Company sent an embassy from Bombay (modern Mumbai) to attend Sivaji's coronation at his castle at Rairy, where he was weighed in gold in the tradition of Hindu kings.

148

Indeed, by the

1670s Mughal alarm at Sivaji's revolt was enough for the emperor Aurangzeb to abandon the court city at Shahjahanabad and spend the rest of his long reign (1658â1707) in endless peripatetic campaigns to bring the Marathas to heel. Aurangzeb achieved a short-lived victory in 1690 (Sivaji had died in 1680). But by the time of his death, in 1707, Mughal power had been driven out of western India

149

â a defeat that was eventually formalized in the

farman

or imperial declaration of 1719. Aurangzeb's reign came to be seen by later historians as the climax of the Mughal era, and his death as the signal for a new dark age of imperial collapse, from which India was rescued by British intervention after 1765. Humiliated by the Marathas, unable to staunch the haemorrhage of power to their provincial governors or

subahdars

, and challenged by the rise of Sikhism in the Punjab, Mughal prestige was finally shattered by the invasion of Nadir Shah, the ruler of Iran. Indeed, Nadir's victory in 1739 was the starting gun for chaos. Maratha, Rohilla (Afghan) and Pindari (mercenary) armies, and those of lesser warlords, ravaged North India. In this predatory climate, trade and agriculture declined together. Economic failure echoed political disintegration. Small wonder, then, that Mughal India was the first of the great Eurasian states to fall under European domination after 1750.

In recent years, this simplistic âblack' version of India's pre-colonial history has been largely rewritten. The late Mughal period no longer makes sense as the chaotic prologue to colonial rule. India's conquest was a more complex affair than the foredoomed collapse of an overstretched empire and the pacification of its warring fragments by European rulers with superior political skill. A realistic account of the half-century that ended at the Battle of Plassey in 1757 (the opening salvo of Britain's colonial conquest) would stress the part played by Indians in building new networks of trade and new regional states. It was this that helped to set off the crises that overwhelmed them unexpectedly in the 1750s.

Indeed, behind many of the changes of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries can be seen the effects of expanding trade, rising population and a growing rural economy. Urban prosperity and the rising wealth of the rural elite made provincial interests less willing to put up with central direction from Delhi. The Maratha revolt was

a symptom of this. The Maratha confederacy has long been portrayed as a predatory horde that reduced northern India to anarchy. But behind its rise can be seen something more interesting than an alliance of freebooters. The Marathas' territorial conquests were marked not by scorched earth but by their elaborate revenue system, whose voluminous records are preserved at Poona (modern Pune).

150

Maratha leaders aimed not at general devastation but at the gradual absorption

of the Mughal domain into the sphere of their

svarajya

or âsovereignty'. Their object was not so much the absolute overthrow of Mughal power as its enforced devolution: hence the eagerness with which they sought to cloak their rule with the authority of Mughal grants and decrees.

151

The Maratha enterprise, suggests a modern study, is best seen as the struggle of an emerging Hindu gentry, under their

sardars

or chiefs, to share Mughal sovereignty and revenues in ways that reflected the rising importance of new landholding groups.

152

In other parts of the Mughal dominions a similar pattern can be seen as the

subahdars

tried to slacken Delhi's grip as part of their effort to manage the demands of local magnates. In Bengal, Awadh (Oudh), Hyderabad and the Punjab (where

declining

trade was strengthening Sikhism), weakening Delhi's grip meant not so much a slide into anarchy as a new phase of state-building by local rulers who were anxious to pose as the legitimate representatives of the old imperial regime.

153

Conceivably this trend might have led to a more decentralized Mughal âcommonwealth' as Mughal institutions were adapted to the needs of different regional powers. Maratha influence, based on formidable military power, might have become as widespread as that of the Mughals had been. Instead, two great destabilizing forces interacted to make Mughal âdecadence' the prelude to a revolution. The first was the impact of a new round of invasions from Central Asia, the traditional source of new hegemonies in India. In 1739a huge Mughal army surrendered at Karnal in the approaches to Delhi. âThe Chagatai [i.e. Mughal] empire is gone,' groaned the Maratha ambassador, who fled from the scene, âthe Irani Empire has commenced.'

154

The subsequent capture of Delhi by the Iranian ruler Nadir Shah (he entered the city on a magnificent charger, with the humiliated emperor in a closed palanquin), followed by the Afghan incursions in the 1750s, wrecked Mughal prestige and devastated the old trade routes between Bengal and Upper India. A vital part of the Mughal heartland west of the Indus and around Kabul was wrenched away by defeat.

155

In a further battle at Panipat, in 1761, the Afghans crushed the Maratha army and killed the

peshwa

, chief minister of the confederacy.

The second great source of subcontinental change was the rapid

integration of maritime India into international trade. In Bengal, the breakneck conversion of marsh and forest into ricelands and the huge workforce of cotton weavers and spinners (perhaps 1 million or more) created an exceptionally dynamic economy, whose growth was fertilized by the inflow of silver with which Europeans paid for their purchases of cotton and silk. Along the Coromandel coast south of Madras, in modern Tamil Nadu, a similar pattern of agrarian success and textile production created a flourishing mercantile economy in a region that was also the crossroads for trade in the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.

156

Here, as elsewhere in coastal India, a distinctive type of mercantile capitalism had grown up to finance and manage the production, sale and distribution of textiles and other commodities.

157

From the late 1500s onward many Europeans came to India to try their luck in its courts and commerce. However, it was maritime India's trade that was the main attraction. By the eighteenth century, European warehouses (or âgodowns') and âfactories' dotted the peninsular coast from Surat to Calcutta. Some Europeans, like âDiamond' (Thomas) Pitt, came to India as âinterlopers', defying the monopoly claimed by the chartered companies. Some, like âSiamese' (Samuel) White, turned into freelances. White arrived in Madras in 1676. But he soon crossed the Bay of Bengal and made his way to Ayudhya, then the Siamese (Thai) capital. He made his name first in the elephant trade â the dangerous business of bringing elephants by sea across the bay to India â before becoming the king's chief commercial agent.

158

But most European traders were company men. The high costs of long-distance trade, as well as large armed ships (the âEast Indiamen'), shore establishments (with their garrisons to guard against attack by other Europeans or disorderly locals) and the diplomatic apparatus required for dealings with regional rulers and the Mughal court, had long made it necessary for European traders to be organized as joint-stock companies. These were forerunners of the modern corporation (with shareholders, a board and a management structure), and enjoyed a monopoly in the direct trade between their country and India. But their superficial modernity did not, of course, mean that European merchants were heralds of the open economy or the rule of the market. Indeed, they had little to sell, and they were forced to import bullion on a massive scale to pay for the Indian goods that

they wanted to buy. Their commercial policy was to drive down the price and increase the quantity of the Indian textiles for which an insatiable demand existed in Europe. Hence the rival European companies (mainly after 1720 the English and French East India companies) were engaged in a constant effort to entice Indian weavers into their trading towns (like Madras or Pondicherry), where they had been allowed to build their âfactories' and exert their control over weavers and merchants in order to regulate the price, type and quality of the cloth produced.

159

This led them into close but often quarrelsome relations with local rulers, whose wealth and power also depended upon the profits of trade and the shuffling of tax revenues between commerce and credit. By the early eighteenth century, the threat of a boycott or a blockade of a port had become a powerful counter in the companies' diplomacy. Yet they still found it wise to show studious deference to the Mughal emissaries who arrived periodically, taking care to dress up in their Mughal robes â for wearing the robes that the ruler had granted was the symbolic affirmation of obedience and loyalty.

160

The Mughal defeat in 1739 sent a shock wave across South Asia. But at the moment when the young Robert Clive landed at Madras, in 1744, the idea that any of the European companies, let alone the English, with their dilapidated fort at Madras, could become a territorial power in India, let alone ruler of the whole subcontinent, was almost absurdly improbable.

South Asia in the first half of the eighteenth century should not be seen as a region that was drifting from stagnation to anarchy. In the northern interior the triangular conflict between Marathas, Mughals and the transmontane invaders was also a struggle between âgentry' groups, who were striving to build a stable and sedentary order of towns, markets and settled agriculture, and âwarrior' groups who were part of the old tradition of nomadic pastoralism on the upland plains connecting northern India and Central Asia.

161

The economic and social change of the long Mughal peace brought that conflict to a head. Similarly, in maritime India, commercial expansion was rapidly transforming the economic and social order and relations with both the Indian interior and the outside world. Here then was a double revolution in the making: a âcoincidence' that was to hurl South Asia into its modern, colonial, era. But only the most visionary of prophets

could have forecast in 1740 that the outcome of that revolution would be the conquest of the whole subcontinent by just one company of those European traders who seemed to find mere physical survival in the Indian climate an often fatal challenge. For such was the lottery of death and disease that one in every two who arrived from Europe could expect to die in his first year in India.

The invasions of North India in 1739 by the armies of Nadir Shah and in the 1750s by his former henchman Ahmad Shah Durrani (Nadir had been murdered in 1747) were something more than random tribal incursions of the kind that had disturbed the Indian plains for centuries past. Together they formed the last great effort at empire-building in the tradition of Tamerlane, tearing down in the process the Mughal and Safavid states. The Safavids were the first victim. Squeezed between Ottoman-dominated Mesopotamia and Anatolia in the west and a vast tribal hinterland stretching east and south to Herat and Kandahar in modern Afghanistan, Safavid Iran had always represented an uphill struggle to impose the authority of the city and the sedentary world on the steppe and the desert. Georgia, the main recruiting ground of its slave army and bureaucracy, was especially vulnerable to Ottoman and Russian pressure.

162

Politically, the Safavid system had been a precarious amalgam of a Turkic tribal alliance with the Iranian literati: but no real fusion had taken place. By 1700 this unstable coalition was coming under increasing external and internal strain.

Safavid rulers based in Isfahan had been no more successful than the Mughals in achieving an empire of fixed territorial boundaries. They had won and lost Baghdad. Their grip on Khorasan, Herat and the city and region of Kandahar had never been secure. Kandahar had been conquered by Uzbeks in 1629, captured by the Mughals in 1634, and recovered by Shah Abbas II in 1650. In 1709â11 the Safavids lost control of it to the Ghilzais, the dominant tribe in the southern Afghan lands. Herat and Khorasan had slipped from their grasp by 1718â19. In 1722 the Ghilzai leader Mahmud shattered the Safavid army at Gulnabad, captured Isfahan, and seized the throne abandoned by the shah. Both Russia and the Ottomans, perhaps mutually fearful, rushed to exploit the Safavid collapse. Peter the Great took Derbent, Resht and Baku along the Caspian Sea. The Ottomans grabbed Tiflis

(1723) and, with Hamadan, Erivan and Tabriz, much of western Iran. In a chaotic decade, the imperial legacy of Abbas I had been summarily dissolved.