After Tamerlane (25 page)

Authors: John Darwin

Why and how had this happened?

In the mid eighteenth century, an uneasy equilibrium still characterized the relations between the states and empires of the European, Islamic and East Asian worlds. That was also true of the balance of advantage between all the Eurasian powers on the one hand and the indigenous societies of the Outer World â in the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia and the Pacific â on the other. That is not to say that the position was static. The frontier between the European powers and the Ottoman Empire had moved backwards and forwards since the early years of the century. But, although the Ottomans had been forced to fall back since their last great invasion of Europe, in the 1680s, they had recovered ground lost before the 1730s and had stabilized their defence against Austria's advance in

the Balkans. In the north, where they faced the endemic expansion of Russia, the approaches to the Black Sea â still an Ottoman lake and the strategic shield of their northern provinces â remained in the hands of their Muslim clients the Giray khans of the Crimea. On the coasts of North Africa and the Levant, the European maritime powers showed little desire (or lacked the means) to upset the Ottoman paramountcy that still survived there. Further east, around the Caspian Sea, Russian moves south from the Volga delta had made little progress, although there was a vigorous commercial traffic connecting the Russian towns with Iran, Central Asia and North India.

1

The 1740s were a turbulent period in India, when Iranian, Afghan and Maratha invasions struck at the heartlands of the Mughal Empire, while its old coastal tributaries â especially Bengal â asserted increasing autonomy. The chartered companies of the British, Dutch and French had forts and âfactories' scattered round the coasts of South Asia, and had come to blows with each other in the 1740s. But in 1750 it would have seemed absurd to predict that the struggle for empire on the plains of North India would end in the triumph of a European rather than an Asian imperialism. A far more likely outcome appeared a division of the spoils between Afghan and Maratha empire-builders, while maritime India followed a different and more cosmopolitan trajectory. In the greatest empire of all, the threat of geostrategic upheaval looked less likely than ever. The Ch'ing monarchy was preparing the final destruction of nomadic military power on the steppes of Inner Asia, the oldest and deadliest threat to the East Asian âworld order'.

2

When this was accomplished (Sinkiang, or East Turkestan, was conquered by the end of the decade), the Celestial Empire would be still more massively impervious to external disruption, less willing than ever to make any concession when importunate visitors knocked at its maritime back door. Or so it appeared.

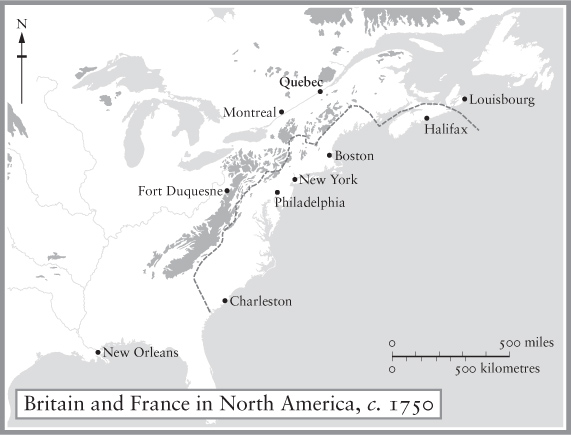

In the Outer World, too, there was little to hint that a decisive shift towards European hegemony was about to take place. The stand-off between the French and the British in North America (a function in part of their European relations), and the French alliance of convenience with the interior Native Americans, had halted the line of European settlement along the eastern foothills of the Appalachians. The advance of the Spanish from their Mexican base had also been

stalled. The semi-arid Great Plains and their mobile, warlike peoples blocked one line of expansion; the remoteness and apparent inhospitality of the California coastline discouraged the other. (The Spanish did not occupy the San Francisco region until the 1770s.) In South America, vast regions of forest and pampas â in Chile, Argentina and the Amazon basin â resisted the feeble assault of Creoles and (Spanish-born)

peninsulares

. In sub-Saharan Africa, Muslim influence diffused into the western savannahs, and drifted up the Nile towards the Coptic redoubt of Ethiopia.

3

It drew the East African coastlands towards the Persian Gulf and India. But Europeans scarcely ventured beyond the beachheads of the slave trade in Atlantic Africa. In the far south, the Afrikaner âtrekkers' in the Cape interior were hemmed in by San (the old word is Bushmen) to the north and west and by Nguni communities to the east.

4

Most striking of all, in 1750 surprisingly little was known of the geography of the Pacific, though it had been traversed many times by European navigators. The shape and ecology of Australasia, the location and culture of the Pacific islands, and the Pacific coast of what is now Canada were blanks or fantasies on the European map. As late as 1774, an authoritative map declared Alaska an island.

5

The frontiers here had yet to be found.

Eurasia's equilibrium had not meant peace. Between 1700 and 1750, as well as the wars between Iranians, Afghans, Marathas and Mughals, there were major wars between the European states, between Europeans and Turks, and between Turks and Iranians. But after 1750 the geopolitical scene was doubly transformed. The scale and intensity of Eurasian conflicts became much greater, and their âknock-on' effects outside the Old World much more disturbing. The reasons behind this remain somewhat mysterious. But part of the answer may perhaps be found in the explosive convergence of two longer-term trends. Both were connected to the quickening pace of the commercial economy in the mid eighteenth century. The first was the pressure to secure and extend the markets and trades whose value was rising and protect them from rivals, or predatory intruders. This pressure was felt (and transmitted) by Asian merchants and rulers, by American traders and settlers, and by European monarchs and ministers. A spate of short wars over land and trade might have been the result. But commercial growth sparked the critical phase of a more

insidious trend. In eighteenth-century Eurasia it was fiscal strength and stability that determined the scale of state military power. This was not just a matter of a large revenue base and the collection of taxes. It presupposed also a close (and mutually profitable) connection between the public officials and the interests that managed the financial market, where the state was usually much the largest client. Possessing a well-developed financial system, able to mobilize funds quickly and cheaply, was the key to maintaining a loyal and well-equipped army. The expansion of trade thus contributed directly to war-making power, and financial resources became the ultimate arbiter of military fortune. âA financial system⦠constantly improved, can change a government's position,' remarked Frederick the Great, who knew a thing or two about both. âFrom being originally poor it can make a government so rich that it can throw its grain into the scales of the balance between the great European powers.'

6

By 1815, governments in London had ten times the revenue enjoyed by their predecessors a hundred years earlier. The âfiscal-military state' did not by itself create conflicts and crises. But, by changing the rules that governed success, it opened the way for a new pattern of power.

There were two epicentres of geopolitical turbulence in mid-eighteenth-century Eurasia. The first was in Europe. The immediate causes of European tension seem obvious enough. Most European states were instinctive expansionists. In a pre-industrial age, power was equated with the possession of land and the population it carried, or with a trading monopoly in tropical produce with its glittering promise of a surplus of bullion. Dynastic ambition and mutual suspicion raised the territorial stakes. In Western Europe, the four-cornered struggles of France, Spain, Britain and the Netherlands over the previous century had turned on the question of whether Britain or France would be the dominant power in Atlantic Europe, with effective control over the maritime access to Europe's Atlantic extensions in North and South America. The other great pole of European antagonism was an âinland America': the vast open frontier of Eastern Europe.

7

This region was notionally shared between four sovereign states: Russia, Austria, Poland and the Ottoman Empire. But the impression of Polish and Ottoman weakness sharpened the land hunger of their stronger neighbours and fuelled their mutual suspicions. Until

the mid-1750s, the precarious stability of a quarrelsome continent was chiefly maintained by the primacy of France, the strongest power in the European world. If France had been denied an outright hegemony under Louis XIV, it remained the arbiter of Europe's diplomacy. It had the largest population, the biggest public revenue and the strongest army of any state in Europe.

8

Together with great cultural prestige, a well-developed commerce, an impressive navy and the most sophisticated apparatus of diplomacy and intelligence, these made up an apparently unbeatable combination. Even if France could not dominate Europe, it could hope to regulate the continent's affairs in ways that secured its own pre-eminence.

This aim was pursued through a careful diplomacy of checks and balances. France supported a party in Poland to blunt the incipient domination of Russia and the European ambitions of the Romanov tsars. It allied with Prussia to maintain pressure on Austria, and with the Ottoman Empire to frustrate the expansion of both Austria and Russia. The Bourbon âalliance' between France and Spain (both of whose monarchs were Bourbons) was meant to defend the status quo in the Mediterranean and Italy. Since the French and Spanish fleets together usually outnumbered the British, it also served to limit Britain's maritime prospects in the Atlantic basin. Thus the âconservative' primacy of France served unwittingly to uphold the larger equilibrium in Eurasia and the Outer World. It helped to guard the Ottoman Empire against an overwhelming combination of European enemies. It checked the influence of the English East India Company in South Asia. It blocked the way to the North American interior from the coastal settlements of the British colonies with an âIndian' diplomacy directed from the impregnable fortress at Quebec.

The French system was far-flung, but its burdens were great. France had to be the greatest military power in Europe and maintain a standing army poised to intervene in Germany against Austria or Prussia. It had to compete with the British navy to preserve the Atlantic âbalance' and protect its colonial empire in the Caribbean, where its valuable sugar colonies rivalled the British. France must also be a Mediterranean power, with a fleet at Toulon to watch its interests in Italy, and keep the Near Eastern balance between the Ottomans and Austria â France's main rival in Europe. Financing this huge apparatus

of naval, military and colonial power was a constant strain on the Bourbon monarchy and the state it had fashioned. After 1713 the massive army that Louis XIV had deployed (over 400,000 men) had had to be cut back to no more than half that number. By the mid-century years it was already a question whether France's real future lay in Atlantic trade and the growth of its colonies (the lifeblood of ports like Nantes, Bordeaux and La Rochelle), or in preserving and strengthening its continental position â and whether the revenues of the Bourbon state could bear the burden of both.

In the mid-1750s the precarious stability that French power underwrote began to break up. The French âsystem' was challenged simultaneously in both west and east. The disruptive force was the rising power of both Britain and Russia, at a time when French military strength had reached its practical limit under the old regime. Russia could no longer be excluded from Europe; while Britain's financial muscle was now sufficient to fund a war-winning navy, two American armies and the subsidies needed for its allies in Europe. The result was a continental and maritime war that broke the back of Bourbon diplomacy. The Seven Years War of 1756â63 smashed French primacy, but replaced it with nothing. It set off instead a geopolitical explosion. The age of war and revolution that followed in its wake lasted more than fifty years, until a new and experimental five-power âconcert' (of Britain, France, Russia, Prussia and Austria) emerged at the Congress of Vienna in 1814â15.

The cracks appeared first in France's Atlantic defences. In the War of the Austrian Succession (1740â48) France had upheld its overall position. But in North America there were obvious signs of weakness. The great French fortress at Louisbourg, which guarded the naval approaches to the St Lawrence, France's main access to the American interior, was captured by a colonial army of Anglo-Americans with the help of the British navy. At the end of the war, the British (who were forced to hand Louisbourg back) constructed a new base at Halifax in Nova Scotia. Further south, British traders from the thirteen colonies competed energetically for the trade of Native Americans in the interior. Shorter lines of supply (compared with the river labyrinth that connected the Ohio valley to Montreal and Quebec) and cheaper credit and goods gave them the advantage. By the early 1750s the

French were worried enough to construct Fort Duquesne (on the site of modern Pittsburgh) to shore up their influence over the Ohio tribes and keep British traders at bay. But the pressure from the British side of the frontier was also growing. A war of maps had already broken out, with a British map of 1755 claiming the land west as far as the Mississippi. Traders, settlers, land speculators and even missionaries were determined to contest France's claim to the interior,

9

resting on the seemingly flimsy support of their alliances with native peoples