After Tamerlane (26 page)

Authors: John Darwin

and on a skeletal force of soldiers, priests and French Canadian woodsmen. In the British colonies, where elected assemblies and local interests were extremely powerful,

10

westward expansion seemed the only escape from economic stagnation, a view shared by many of the London-appointed governors. Probing the weaknesses of France's ill-defended monopoly became an irresistible ploy. It was just one of these expeditions, led by the young Virginian surveyor George Washington, that lit the fuse for an Atlantic war.

Washington's venture ended in disaster. His small force was sur

rounded by the French and their Native American allies. Some of his followers were killed. He was sent back to Virginia. But both sides reacted sharply to this frontier incident. To the French it seemed proof that the British intended a renewed assault on their inland empire and its headquarters at Quebec. So reinforcements were dispatched the following year (in 1755). But in London the French attempt to tighten their grip on the inland routes, the building of Duquesne and the treatment of Washington were regarded as provocative and threatening: a direct challenge to Britain's colonial future on the North American continent. An outcry arose from âAmerican' interests and their political friends. A fleet was dispatched to intercept the French reinforcements before they could cross the Atlantic. It failed to do so. But the naval skirmishing that followed began a new Atlantic war.

By itself such a war might not have endangered France's general standing. The British attempt to capture Quebec â the grand citadel of French North America â might have been foiled, as so often before, and the British disconcerted by the threat to their interests in Europe. But the American quarrel between Britain and France ignited a second explosion, in Eastern Europe. âThe turmoil in which Europe finds itself', wrote Frederick the Great in 1757, âbegan in America⦠Thanks to our century's statecraft, there is now no conflict in the world, however small it may be, which⦠does not threaten to engulf the whole of Christendom.'

11

The heart of the problem was the political disintegration of Poland, a vast ill-organized aristocratic republic stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Poland was the key to French diplomacy in Eastern Europe. Its survival placed a limit on the power of Prussia, and reinforced its dependence on France's goodwill. It kept Austria in check, and limited Russia's capacity for interference in Europe. By the 1750s, however, Poland's elected kings were the puppets of Russia â a trend that encouraged a growing rebelliousness in the Polish nobility. The temptation for the Prussian king to embroil himself in Polish rivalries, and renew his challenge to Austria as the great German power, became almost irresistible.

12

He might have hoped to rely on his grand ally, France. But the Bourbon government was determined to keep the status quo in the East, and especially keen to prevent Austria from joining the Anglo-French struggle on the side of

Britain, its traditional ally.

13

In an astonishing reversal of historic antagonism, the Bourbon and Habsburg monarchies reconciled their difference and joined forces to repress an insurgent Prussia. This was the âdiplomatic revolution' of the eighteenth century, an event as stunning to contemporaries as the NaziâSoviet pact of August 1939. The Franco-Austrian alliance brought together the two most powerful states in Europe. It should have secured a âconservative' peace, helping France to settle her colonial differences with Britain. Instead, by tenacious resistance and a series of remarkable victories, Frederick the Great humiliated his great-power enemies. The militarist bureaucracy he had created proved a match for a distant France and an ill-organized Austria. Frederick could not win outright. But, with British subsidies and the damage the British were doing to France's Atlantic interests, he held out long enough to force his enemies to the conference table.

Now French primacy unravelled in earnest. While Frederick had held his own in Europe, the British had slowly assembled the force they needed to conquer New France in North America. In 1759, âthe year of victories', they won naval control of the Atlantic, cutting off the French in Canada from reinforcements. In September â in the nick of time before winter set in, the St Lawrence froze and the British fleet had to withdraw â General Wolfe captured Quebec, the key to French power in the American continent. It was a staggering blow. For (though they nearly lost the city to a French counter-attack in the grim winter of 1759â60) the British could now roll up the French system of influence in the continental interior. And, with France on the ropes in the Atlantic, the British began to threaten its junior partner, Spain, whose American empire was painfully exposed to their naval and military power. The year of decision was 1762: the British captured Havana, the Gibraltar of the Spanish Caribbean. Spain was desperate for peace. France was close to bankruptcy â indeed, it had been technically bankrupt since 1759, when it defaulted on its loans. Russia changed sides. A new tsar, star-struck by Frederick the Great, abandoned the war against Prussia.

The peace that followed in 1763 was really a truce of exhaustion. The French were driven from the American mainland, keeping their sugar-rich Caribbean islands and their fishing platform (the islands of

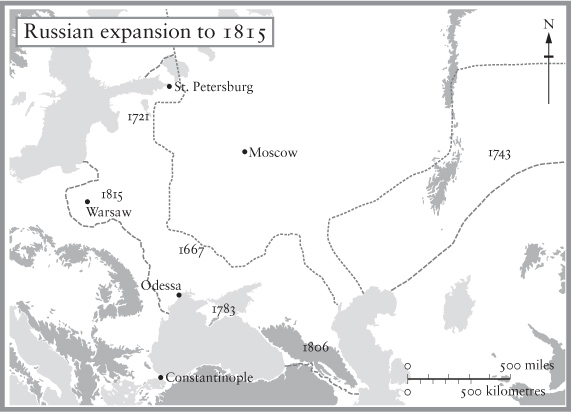

St-Pierre and Miquelon) near Newfoundland. Louisiana went to Spain, which lost Florida to Britain. But the real decision of the Peace of Paris was that France was no longer the arbiter of Europe. The French âsystem' had been broken. The next thirty years saw the progressive demolition of the old geopolitical equilibrium in Eurasia and the Outer World alike. The aggrandizement of the British could no longer be checked. In Eastern Europe and in Middle Eurasia, the main beneficiary of France's decline was the imperial Russia of Catherine the Great (r. 1762â96). Without the shadow of help from its usual protector, the Polish republic was eaten alive â in stages. The first partition was in 1772, when Russia, Austria and Prussia each took a bite. The Russian share was the eastern borderlands. What remained of Poland was now de facto a Russian protectorate under a client king, Stanislaus Poniatowski (one of Catherine the Great's lovers). The Polish agreement left the Russians free to complete their war against the Ottomans (1768â74) and gain their long-cherished objective: a firm foothold on the Black Sea at Kherson, under the Treaty of Kuchuk Kainardji

in 1774. In 1783 they annexed the Crimean peninsula and made themselves masters of the Black Sea's north shore. Grigori Potemkin (Catherine the Great's favourite and lover) unleashed his furious energy as viceroy of âNew Russia'.

14

Another war against the Ottoman Empire (fought by the Turks in a vain attempt to reverse their losses) brought a new round of prizes. Odessa was founded in 1793 to be the metropolis of this new southern empire. The road had been opened to conquer the Caucasus, and perhaps even Constantinople. It was a critical phase in the ascent of Russia as a global power.

The course of British expansion was much less heroic. The British had felt the strain of war, and the pressure to compromise was strong. In this mood of financial stringency, the burden of a new American empire was almost an embarrassment. The thought of new commitments there was horrifying. So British ministers made haste to tranquillize their new acquisitions, not to develop them. They appeased the French Canadians in the new province of Quebec, and refused to set up the elective assembly demanded by incomers from the thirteen colonies. Quebec was to be governed as a military colony to supervise the old French sphere in the American Midwest. To the fury of the American colonists, a âProclamation Line' was drawn along the Appalachian mountains. Far from being the spoils of American victory, the interior was to remain an âIndian' country, closed to American settlers and policed by imperial officials in the interests of peace, and financial economy. As if this was not enough, the British were also determined to force the American colonists to meet some of the costs of imperial defence. The colonists were to pay imperial taxes â like the notorious stamp duties. Colonial trade was to be more closely regulated to enforce the navigation laws prohibiting foreign trade where it bypassed ports in Britain and to suppress the widespread practice of smuggling.

The sequel is well known. The settlers rebelled. The British mismanaged what was anyway a difficult war with a long and uncertain supply route across the North Atlantic.

15

When they failed to deal quickly with the colonial revolt, their Atlantic triumph of 1763 became increasingly frail. Their maritime rivals, eager to restore the Atlantic balance, seized the chance for revenge. In 1778, three years after the beginning of the colonial war, France, Spain and the Netherlands joined in. Isolated, and outnumbered at sea, the British lost

control of the Atlantic for a crucial period, sealing their fate in America. At Yorktown in 1781 their main army in the colonies surrendered. Though their naval defeats were reversed â frustrating the hopes of the French, Spanish and Dutch â the British were forced to accept American independence at the Peace of Versailles in

1783

â though they kept control of Canada.

On the face of it, the great British victory of 1763 had been almost completely reversed in just twenty years. But if we think in global terms we can see that the successful revolt of the British white settler societies against imperial control was really a final confirmation of the âprovisional' triumph of 1763. Now at last the American interior was fully thrown open to the âneo-Europeans' of the Atlantic seaboard. As soon as the war was over â indeed even while it continued â the colonists began to swarm across the mountains. One of the earliest acts of the âUnited States' was to lay down a programme for territorial expansion in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. As the tide of settlement flowed into the Ohio valley and the Old Southwest (modern Alabama and Mississippi), the inevitable friction with indigenous peoples detonated a series of frontier wars. Divided, outgunned and increasingly outnumbered, the Native Americans were driven steadily westward while the land they left behind was filled up with white men and their slaves. By 1830 the tide of white settlement had raced ahead to reach and cross the Mississippi.

16

In fifty years a âneo-Europe' on the American continent had emerged from the struggling colonies of the Age of Equilibrium.

In North America, the richest region of the Outer World had now been prised open for European occupation. But the most dramatic invasion of the Outer World after 1750 took place on the other side of the globe. In the flush of victory, and with a novel sense of its (worldwide) supremacy, the British navy launched a systematic drive to chart the oceans, winds and currents: the vital intelligence of maritime power in the age of sail. One of those chosen for these mapping expeditions was James Cook, who had made his reputation as a skilled navigator in the attack on Quebec in 1759. Nine years later he led the first of his three voyages into the Pacific, to observe the transit of Venus and also to verify whether âa continent, or land of great extent, may be found to the Southwest'.

17

A decade of exploration followed

before his death in Hawaii after a quarrel with the islanders. Cook's reports (and those of his scientific passengers, such as Joseph Banks) were sensational. They revealed a vast Pacific world of which Europeans had had barely an inkling. The societies and cultures of the Pacific islands struck the European public as a tropical Eden, a paradise of leisure and innocence. But Cook's revelations had more than a cultural significance. His voyage to the Pacific coast of modern Canada hinted that a new trade route could be opened between the fur-bearing regions of North America and a lucrative market in China. His greatest discovery, however, lay in the South Pacific. Cook exploded the myth of a Great Southern Land stretching south to the bottom of the world. Instead, he accurately charted the island continent of Australia, and on 22 August 1770 claimed its eastern half for Britain. He had already circumnavigated New Zealand. Within ten years of Cook's death the British government had established the first of the convict settlements in eastern Australia, perhaps partly to tighten its grip on the southern sea route that ran between the Indian Ocean and China. By the 1790s, European and American whalers, sealers, traders, missionaries and beachcombers were beginning to arrive in force in the Pacific islands, including New Zealand. Settlement was slow in what was still a region remote from Europe, subject to the âtyranny of distance' and the threat of interference by France. But by the 1830s the colonization of Australia was fully under way, carried on the back of the wandering sheep. In 1840, British settlers arrived in New Zealand. A second âneo-Europe' (perhaps to rival the Americas) was in the making.

The thirty years after 1763 thus saw a huge extension of Europe's grip on the territorial resources of the world, although the wealth of the ânew lands' was as yet more prospective than actual. What made this all the more significant was that it coincided with a no less dramatic shift in the balance of power in the Old World of Eurasia, forming the double foundation of European supremacy in the nineteenth century. This shift could be seen in the Islamic realm, in India and, by the 1830s, in East Asia as well. The arrival of Russian power (in strength) on the northern shores of the Black Sea in the 1770s and ' 80s marked a crucial stage in the opening of the Islamic Near East to European political and commercial influences.