All Roads Lead to Austen (12 page)

Read All Roads Lead to Austen Online

Authors: Amy Elizabeth Smith

***

The night before leaving Mexico, I tried to work up the nerve for a Relationship Talk with Diego. I usually didn't have trouble with this kind of conversation; I wasn't sure why I was finding it so difficult just then. When Diego saw me looking earnest over dinner, he asked what was on my mind. “You're still not feeling well, are you? Or are you thinking about your friend who died?”

“I'm still run down, but I'm getting used to that by now.”

“Then what's wrong?”

“Well, it's just that I wanted to talk about”âI fidgeted with my spoonâ“about this visit, about where I'm going from here. Aboutâ¦Austen. You don't know how much I appreciate your help with all of the planning and rescheduling!”

Chicken

.

“It was fun!” he responded. “You know how much I love to read, but I've never done anything like this. Knowing we'd talk about the book with other people made me think a lot more about it.” He reached over and grasped my hand firmly across the table. “Didn't the groups turn out the way you planned?”

“It was a shame about splitting into two but aside from that, I'm very pleased,” I reassured him.

But even as I responded, I was struck with the answer to my reticence, because there

was

something that hadn't turned out the way I'd plannedâDiego and I. Before I'd arrived, I'd imagined that we'd stay in touch via email but that I'd move on, that he'd meet another woman in his taxi or out dancing, or maybe on the beach or at church. I had never imagined that I'd develop such feelings for him, that he'd want me to move back, that the thought of leaving this warm, patient, loving man would make me feel like I was about to head for Antarctica, not the equator. Was there any way we could work things out after all? Could we actually find a way to be together in the end?

To disguise the depth of my concerns, I avoided his eyes and dodged back into Austen. “Anyway, I didn't really have anything specific planned for the groups, although I was curious about one thing. Lots of Americans tend to relate to Austen very personally, and I wondered if you and your friends would do the same.”

“Wasn't that funny about Josefa and Juan's older daughter?” He caught my meaning immediately. “There's plenty of reason to think that things with Marianne and Colonel Brandon will work out just fine, but those two were both thinking about their daughter's older husband.”

“Salvador brought up some points about parenting I'd never considered before, as many times as I've read

Sense

and

Sensibility

. That really struck me. He also spent more time talking about being honorable, on the value of being a good person.”

“Salvador is one of the best men I knowâyou can trust him

completely

. And you can see what good parents he and Soledad are. If your students don't have kids, it's no wonder they don't bring that up. They're not going to think so much about parenting.”

I carried a handful of dishes to the sink. Time for me to 'fess up to my latest cultural cluelessness. “There

is

another thing that surprised me. I guess I was going on stereotypes about Mexicans, but somehow, I thought you'd all like Marianne better than Elinor,” I admitted. “She's much more emotional, warm, and spontaneous. That's the image Americans have of Mexicans, you know. That you're all passionate and crazy, that Mexican men are always getting into knife fights over women, that Mexican women are hanging out on their balconies or running off to war to follow their lovers. Marianne thought dying for love was the best way to go!”

“Only until she almost

did

,” he laughed. “Well, Mexico's a big country. Maybe if you read the book with more people, you'd find some fans for Marianne. It's true we're passionate, but the problem with Marianne was the selfishness. We care about love, but we care about family even more. When you're hurting your family, that's no good.”

Diego took over at the sink, washing the dishes while I leaned against the counter. “I've thought a lot about what you said on feminism that night,” I told him. “The women in Guatemala liked how intelligent and strong Lizzy is in

Pride

and

Prejudice

, but nobody brought up feminism specifically. At first, I couldn't see how Austen focusing on domestic life and personal interactions was feminist, because getting women out of the house is exactly what so much feminism in the United States has emphasized. But I think I see what you mean more clearly now. Austen gave value to something that was undervaluedâthe daily lives of women, the things that mattered to them. In fact, there's a famous feminist from the States who argued that the personal

is

political.”

“Really?” he asked, looking pleased with himself.

“Really.”

“Will you read

Sense

and

Sensibility

with any of the other groups?” He abruptly turned his attention to the sink, piling glasses precariously and struggling to fit the last plate into the strainer. Men are supposedly better at spatial relations, but I've found that doesn't apply to dishes. Then again, given the sudden tense set of his shoulders, maybe he too was agitated about all the things that weren't getting said that night.

As he turned, I saw the solemn look on his candid faceâhis mention of the other groups raised the unavoidable topic of my going. Shame on me. I'd been so caught up in my own feelings, it hadn't occurred to me that he might be just as unhappy as I was.

I resituated his big scary tower of glasses and secured the plate, then took him by the hand. “We'll read

Sense

and

Sensibility

in Chile this spring, after I leave Ecuador. I'm reading each book twice this year to see what kinds of similarities and differences come up. I'll let you know what Chileans think of Marianne. But right now, I'd rather think about the

azotea

.”

There it was, back again, that smile of his I loved so much. Diego was the one, after all, who'd taught me that “to worry” in Spanish was

preocupar

âto be occupied with something before we need to be. Tomorrow I would be gone. There was no way to know how we would feel about maintaining a relationship down the road until I

was

down the road.

No sense worrying about tomorrow, tonight.

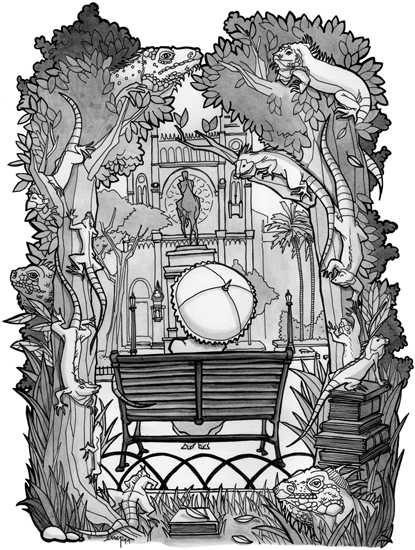

In which the author goes to Guayaquil to visit a stranger who becomes a friend, buys even more books, suffers a setback in her Spanish, solves a few mysteries left over from Mexico, including The Case of the Itchy Red Rash, celebrates Austen's birthday in Iguana Central, meets a bonus reading group, and, best of all, joins an ongoing reading circle of fascinating folks to discuss

Pride and Prejudice

.

Usually I need very strong coffee to wake up. My first morning in Guayaquil, the view from the twelfth-floor balcony was enough. If I hadn't known the Guayas was a river, I would have sworn it was the ocean. Dotted with islands and fishing boats, it stretched as far as the eye could see, flowing powerfully, serenely to the Pacific nearly fifty miles south. I'd arrived well after dark the night before, so this first stunning vista was my introduction to my new home for the next month.

“The pirate port of Guayaquil,” the city is often called in books on Latin American history, and that tantalizing phrase was half the reason I'd wanted to visit. Apparently for centuries every time the good citizens got their houses built and their gardens planted and their curtains hung just so, French and English pirates would sweep through to burn and rape and pillage. At the far left of my balcony vantage point was Cerro Santa Ana, St. Anne's Hill, from which citizens would mount watch for the marauders so they could save their skins, if not their possessions. In today's Guayaquil rows of brightly painted houses wind their way up the steep hill, crowned by a picturesque lighthouse.

Directly below the balcony and stretching for blocks along the river was the Malecón, a boardwalk even more elaborate and attractive than the one in Puerto Vallarta. Back at the turn of the millennium, the city gave it a complete face lift and now, along with the broad river walkway itself, the Malecón hosts gardens, museums, restaurants, upscale shops, and an indigenous artisans' market.

Pirates aside, I'd picked Guayaquil for an Austen group thanks to that classic traveler's resource, the friend-of-a-friend. Betsy, an American who'd married an Ecuadorian, had agreed to arrange the Guayaquil Austen venture. She'd managed to locate an ongoing reading group willing to add

Pride

and

Prejudice

to its December schedule. I was eager to see what perspectives on Austen Guayaquileños might have in common (or not) with Guatemalans.

I'd arrived gruesomely late the night before, but Betsy was as energetic and upbeat as her emails had led me to expect. A blue-eyed blond in her late sixties dressed casually but stylishly, she'd been easy to spot in the crowd at arrivals. She'd whisked me off then set me up in the apartment next to hers, one she and her husband also owned. That next morning when she invited me over for breakfast, I was still on the balcony taking in the singular view.

“This is just the most fascinating thing you're doing, reading Austen in different countries!” she said as she poured coffee. “I'm sorry I can't join you, but I know you'll enjoy both groups!”

This was news to me on two countsâ“can't join you” and “both groups.” I started with the first. “Why can't you join us?”

“We spend December at our house on the coast. Our grandchildren love the beach. We want you to come, too, every weekend, if you can! You'll love it!”

Then she handed me a sheet of paper with names and phone numbers, clarifying the “both groups.”

“The first group I call âMrs. Gardiner.'” Betsy smiled at her own whimsy, a reference to Lizzy Bennet's kind, accommodating aunt. “They're all very warm, very smart. The other one I call âLady Catherine.' I'm not saying they're snobsâthey're just a ritzier group, but they're very well read and interesting. Ignacio José coordinates both. You should talk to him first.”

Ignacio José was, I discovered, a genteelly starving artist, a very talented offbeat writer paid by the groups to serve as a facilitator and literary critic.

“I only mailed six copies of the book,” I said, mentally tallying the readers now involved.

“Mrs. Gardiner has them. I think Lady Catherine bought their own. Actually, even the six you sent almost didn't get here. The customs people assumed we were going to sell them. Why else would anybody want six copies of the same book? They tried to charge extra taxes, and my husband was so mad, he said, âFine, if you think they're so valuable, sell them yourselves!' So they let them through.”

Soledad from the reading group back in Mexico had been curious about the degree of fame Austen achieved in her lifetimeâand while Austen lived to see public acclaim, in her wildest dreams she could never have imagined that nearly two hundred years after her death, in a country of steamy jungles and skyscraping mountains half a globe away, men would be arguing in a crowded post office about a Spanish translation of her dear

Pride

and

Prejudice

.

Betsy then handed me several books. I hadn't mentioned via email that I wanted reading recommendations in each country, but she's such a devoted booklover she couldn't resist sharing.

“These authors are Ecuadorians,” she said. “You'll learn a lot about the culture from them!”

Edna Iturralde was one and the other, Alicia Yánez CossÃo. I tucked the books into my backpack purse, thanking her for getting me started on my newest course of reading.

Since Betsy and her husband were renovating the adjoining apartment, my night there had been a stopgap measure; I'd be spending the month in a comfortable back room in their office suite two blocks away. After helping me lug my fat suitcases the short distance, Betsy handed over the keys.

One of the secrets of long-term travel is to make every temporary abode feel like home, so I set about nesting. In Mexico I'd acquired more things than I could possibly haul away; most I'd left with Diego and his family. The items I'd kept were favoritesâa violet-purple blanket adorned with multicolored fish, an owl statuette with huge, mournful eyes, a bird tile I used as a coaster. Last but not least was Diego's gift, Señor Guapo the stuffed Chihuahuaâa poor substitute for Diego himself, but seeing it always brought back happy memories of the day he'd brought it home to me.

I found spots in my new room for each familiar item, and things seemed cozier already. Too bad there weren't roosters outside to greet me as there had been in Mexicoâalthough over the course of the month I heard men

pretending

to be roosters on three occasions as the local bar shooed customers out for closing time (then again, maybe it was one man, three times).

Homestead established, I stopped at an Internet café to email Diego. There was already a message from him wishing me a safe arrival. I wrote a quick reply, afraid that if I lingered too long over how much I wished he were there with me right then, I'd end up in tears.

I also let my mother know I'd made it safe and sound. The easy part of the café transaction was paying for it, since Ecuador uses U.S. currency, including the Sacajawea dollars that mysteriously disappeared from U.S. circulation. Understanding the clerk was not so easy. Here was a whole new version of Spanish, rapid and contracted, the ends of words often disappearing entirely. A useful phrase like

más o menos

, for instance, which means “more or less,” turns into a single blur of

máomeno

.

I was reduced to the old trick of smiling, faking comprehension, and handing over a bill undoubtedly large enough to cover the total. Oh, boyâdemoted to rank amateur in Spanish once more, unable to carry out the simplest transaction after months of work and slow but steady improvement.

The call in English had gone better. My mother picked up on the second ring, no doubt waiting anxiously since I'd left Mexico. She was pleased I'd made it safely to a new continent, but concern about new dangers surfaced quickly: “I heard on TV about an American farmer getting bit by a vampire bat. They said it came up from South America.”

I could tell from the slight echo that she was using the speakerphone in her bedroom. I could just see her, seated on the bed, which was part of the suite she and my dad had scrimped to buy as newlyweds. The burgundy wood headboard, dresser, and vanity set, meticulously well cared for, had gone from serviceable in the fifties to dated by the seventies to stylishly retro for the new millennium.

Aside from a short stint in Vermont when my father was in the Air Force, my mom had lived her whole life within a fifteen-mile radius of the house where she was born (and I do mean house; my German grandmother considered hospital births a luxury). What had my kind, loyal mother done to deserve a daughter who couldn't manage to stay put? Who flung herself in the path of tropical diseases, battling street dogs, and winged death in the form of bats?

“I've seen lots of pigeons here and some seagulls, tooâbut no bats. Don't worry, I'll be careful!”

***

Ecuador was where Charles Darwin put two and two together on a few important issues when he visited the Galapagos Islands, roughly five hundred miles off the Ecuadorian mainland. My own discoveries weren't quite so dramatic, but it was satisfying for a woman raised on Nancy Drew to finally solve The Bookstore Mystery.

Back in Puerto Vallarta I'd been befuddled every time I asked for a title and the clerk, whether cheerful Marisol or the grim ghost of Pedro Páramo, would pull copies from various shelves around the shopânever from the same location.

That December morning in Guayaquil, when I asked the clerk for Jane Austen novels in Spanish and he began the now-familiar dash from one area of shelving to another, I blurted out impatiently, “Why do you have to look in more than one place?!”

My out-of-left-field bitchy tone stopped him cold, probably more than the question. Arm poised in midair reaching for a book, he stared in injured surprise.

“I'm so sorry!” I apologized, appalled at my own behavior. “I don't feel well.” I was still frustratingly weak and tiredâbut I also felt genuinely irritated that I'd arrived in yet another country with an unfathomable system for organizing books. My mother was a

librarian

, for cryin' out loud. I was supposed to be good at this stuff!

He shrugged and laughed, saying something that resembled “Don't worry!” Then he handed me a copy of

La

AbadÃa de Northanger

. Grateful for his patience and his Austen discovery, I repeated more calmly, “Why aren't all the Austen titles in the same place?”

It took me one more try to understand his accent, but finally the light bulb went on.

Organized

by

publisher

. It should have dawned on me sooner, but I just couldn't get my head around it.

“Why do you do that?” I asked.

He shrugged again and said, predictably, “Why not?”

So you don't have to look in five places for one title? Because most people care about the author, not the publisher? I was incapable of responding without sounding like a harpy, so I didn't. A core value of multiculturalism holds that there's no such thing as good or bad when it comes to culturesâjust “different.” On child labor laws and women's rights, I simply don't buy that, as much as I want to be open to difference. Shelving books isn't exactly a high-stakes venture, but I also didn't see myself returning to the States at the end of the year and reorganizing my books by publisher.

Still, I was pleased to finally know the lay of land and move on to safer territory: my standard request for reading suggestions.

“Nineteenth century?” The clerk's response had more words in it than that, but those were the ones I got. He handed me a volume published by Libresa, plucked from its rightful spot, by local standards, next to all of the other Libresa titlesâ

Cumandá

by Juan León Mera. “Classic,” “school,” “Indians,” and “jungle” were four key words I picked out of his recommendation.

Deciding it was time to retreat to my room before my crankiness resurfaced, I thanked him and turned to pay for my books, but he took them from me with a smile.

Patience

, I urged myself, as he carried the books to a counter where he handed them to a clerk. The clerk wrote down the titles on a piece of paper, which she stamped and handed to me. Then she carried the books to a different counter by the store entrance, directing me to yet another counter.

WTF?!

My stamped slip had a dollar figure on it, so this must be the place to pay. I handed over cash, and Clerk Number Two stamped the slip again. Reporting with my stamped paper to the counter by the store entrance, I was finally rewarded with my books by Clerk Number Three.

What

is

this, the Soviet frickin' Union?

My head throbbing, feeling dangerously close to tears, I sat down outside on a doorstep to collect myself. So Ecuadorian bookstores are slow as molasses, so what? What on earth was wrong with me? Was I afraid to look like a dummy navigating the Byzantine sales system? Was I embarrassed at the setback with my Spanish?

Maybe it really was physical. But could I still be ill after so many weeks? Or was I

losing

it

without Diego? Was I turning into a whiny hypochondriac because I missed his calming influence, his perpetual cheer?

There are few Austen characters less attractive than her hypochondriacs. The best known is Mrs. Bennet, with her “nerves,” and Mary Musgrove of

Persuasion

is a royal pain, too. Emma Woodhouse's father is more endearing since at least he's equally worried on others' behalf, but in Austen's world, dubious health complaints are often shorthand for “Loser!” Apparently Austen's mother was prone in this direction. There are lots of theories as to why Austen's sister Cassandra burned so many of Jane's letters after she died; making sure that none of Austen's (no doubt hilarious) commentary on their mother's complaints survived is one of the more probable ones.

I didn't want to be an Austen Loser, but whatever the problem, I needed a nap. I stopped in a grocery store for some staples, deciding that a bit of chocolate wouldn't hurt either.

“You is beautiful, beautiful,” a man's voice crooned in English just behind me. Knowing I was the only

gringa

in the small store, I refused to turn around.