All That Is Bitter and Sweet (72 page)

It would be impossible to choose a favorite class, but if a measure is how fired up I was, it may have been Diane Rosenfeld’s “Gender Violence, Law and Social Justice” course. In my final paper, I was able to metabolize so many of my life experiences to propose a model that encourages women to engage in a feminist analysis of their own lives and, through strong female-to-female alliances, disrupt the virulent problem of gender inequality in their homes and communities. We can do this by the willingness to become aware, then accept, and finally take action to begin to heal from patriarchal wounding, and from increased personal empowerment commit to service work, addressing gender inequality at the grassroots level.

To suggest a solution, mindful of the many times I have witnessed the power of female-to-female alliances both in the global South and in my own life, I built upon Diane’s and Professor Richard Wrangham’s studies of the bonobos, those wonderful primates I met in the Congo, offering them as a model of how women at the household-to-household level can influence communities into peaceful society. I developed a workshop inspired by the brilliant social architecture of Twelve Step programs, the feminist consciousness-raising groups of the 1970s, and modern sexual abuse and trauma survivor therapy. The workshop would be exportable to any community and open to men as well as women. As Margaret Mead said, every time we liberate a woman, we liberate a man. Also, many men have no idea the effect their addiction to power and degrading women has on us, and them having the opportunity to sit in groups with women who have suffered abuse is an underused strategy. The workshop would incorporate, inter alia, feminist analyses of one’s past and present life, include trauma and shame reduction experiential therapy, role playing, inner child work, art therapy, and identification of compulsive behaviors and addictions, and suggestions for after care and advocacy. The crux of the experience would be for each participant to identify core patriarchal wounding in their life, begin to recover from it, and accept responsibility for advocating feminist social justice change in their communities in whatever way is most meaningful to their personal narrative. Once we begin to recover, we can be most useful in precisely the ways we have been most hurt.

I couldn’t have guessed that my own story would have everything to do with feminist social justice theory and that the gifts I had been given of clinical inpatient treatment and recovery would bring me back to radical feminism.

The paper won a dean’s scholar award. Diane told me when she felt down, she’d read my paper again, and it would put wind in her sails.

I graduated from the Harvard Kennedy School on a glorious day in May 2010, surrounded by some of my dearest friends and members of my families of chance and choice. In a reprise of my college graduation, my mother and sister chose not to attend the ceremony, but Dad was right by my side, along with Mollie. And Tennie, my most wonderful surrogate grandmother, brought her quietly radiant, affirming presence to the commencement, marveling with me at the 468-year-old tradition in I which partook. After I had sung “Fair Harvard” in Latin and had run around hugging classmates and thanking faculty, she presented me with a beautiful necklace on which dangled a key, with a framed reading that said, in part, “There is no more ‘aloneness,’ with the awful ache, so deep in the heart.… That ache is gone, and never need return again. Now there is a sense of belonging, of being wanted and needed and loved … We have been given the Keys to the Kingdom.” The Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Indy Racing League would not excuse Dario from a half day of press obligations related to the 500 (which he would win that weekend for the second time), so he sat in his bus on the track, watching the school’s live Internet feed of commencement, while we chatted back and forth via texting as the exercises unfolded.

After the stately procession through Harvard Yard, the various schools dispersed to smaller venues around the campus to hand out the diplomas. The Kennedy School crowd looked like a United Nations General Assembly, with the foreign students wearing their formal native dress: Africans in colorful dashikis and foulards, Asians in jewel-colored silks. Ever the mountain girl, I went barefoot as I bounded across the grass to accept my diploma. As my little cheering section rose to clap and whoop for me, I felt down to my toes that I was just hitting my stride, that truly anything was possible.

I’m not sure where this journey will take me. All I know is that I’ll always be traveling on the front lines of hope, expecting miracles to happen.

Remembering.

On the path to God, light gives way to darkness, and darkness to light, at intervals. A measure of integration takes place, and we enjoy a moment of peace and joy, but the longing sets in again, and we must again exert the terrible effort.

—CAROL LEE FLINDERS

, Enduring Grace

EPILOGUE

Up on a high ridge in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I walk a narrow footpath ribbed with roots. Dense foliage rubs my shoulders. Some trees I know, but there are more than 400 species here. This park, comprised of mixed mesophytic forest, has more biodiversity than the whole of Europe, so, outside my comfort zone of maple, oak, hickory, larch, walnut, paw paw, persimmon, elm, birch, dogwood, redbud, cherry, buckeye, I have at best, a 1-in-400 chance of naming something. Today, I love knowing what I don’t know.

It is my first long walk since the July full moon. It’s unlike me to not walk, even at night, even if just for a short jaunt to look around, visit the butterflies, watch the turtles in the lake. The woods are spiritually chiropractic. On any given walk, I may not even know I need an adjustment, but once I pass that margin and enter the cathedral of trees and all who live with them, I am changed.

First, I just say, “Hi, God.” Second, I declare my proper relationship with my Creator: I am powerless over people, places, and things; there is One who has all power, and that One is a loving God. Third, I recommit myself to the decision I have made to turn my will and my life over to the care of this Power. A hint of Julian of Norwich’s prayer floats to mind: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well …”

Standing on the edge of a creek, my feet yearn, begging me to step in, anticipating the small, smooth stones a thousand shades of sparkling brown, flashing under rushing water. For today, no further thinking is required. My clothes come off. My body shudders a wordless “ah.”

There is nothing like being in a creek, resting on my back, the water parting at the crown of my head, running along my body. I am baptized every time I lay myself out on the currents, my world view turned upside down, dappled sunlight moving between thousands of leaves floating against the sky.

As I gaze upward, I ponder a few things of which to be conscious during an upcoming trip to Africa, a return to the Congo:

~ Expectations are premeditated resentments.

~ Live life on life’s terms. Be a woman among women, one among many.

~ Do the next, good, right, honest thing. Keep it simple. I am responsible for the stitch, not the whole pattern. Turn the outcome over to God.

~ Ask for help. Write Bishop Tutu, Ted, keep in touch with Tennie. Pray. Cry. Get on the yoga mat. Journal. Read the 104th psalm. Listen to gospel bluegrass.

I feel fear. I have been through this before; I call it a “prescience of grief.” It’s that daunted, jittery moment before a huge wave crashes, and I, standing in the powerful ocean staring at the advancing crest, beginning to seriously doubt the wild abandon and love of adventure that put me in the ocean in front of a wave that could snap my neck. But the fear does not stop me, because more powerful is the certain knowledge that I am less of a woman when I ignore the plight of women elsewhere. My life is richer when I chose to align myself with their realities, share their truth, witness their lives, and admit their pain into my soul.

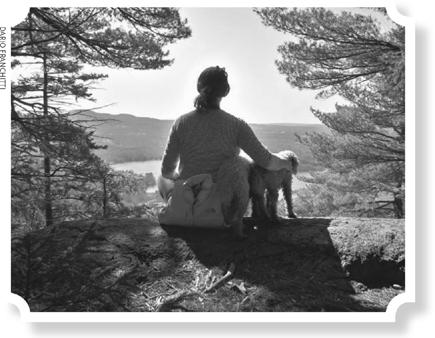

The August full moon has come and gone and I am home once more from Africa. The dogs and I walk in the woods, the creek that runs through our farm calling me. I pick up a green acorn, and think of the ones the squirrels in the Smokys lent me before my trip, the one I placed against my bosom and carried with me, and gave to a child in a slum. Conditions in eastern Congo were even worse than before. I remember traveling across the lakes and over the cruel, dusty roads, visiting forcibly displaced persons camps, and noble clinics inadequately provisioned, working urgently and under duress where girls and women who have survived gang rape sometimes come for treatment. Kika crawled through the bush for a month to reach help. I fell in love with a group of teenage girls at the HEAL Africa clinic in Goma, particularly a thirteen-year-old named Solange. Like the others, she needed surgery to repair the damage her rapists had caused. I remember thinking of Solange and her friends: When they smile, they are fireflies: luminous, magical, just as fleeting.

I nearly lost hope on this trip. The dark night of the soul hit me faster and with more ferocity than ever before. But that is the way it is with Goma. It’s a tough place, perhaps the toughest place I’ve ever been. It challenges the very notion of a loving God. I might even say, Goma defies God. One night in my hotel room, still reeling from the horrors of the day, I wrote an angry letter to God, rejecting the One I had loved in the creeks and woods:

Dear God, These are your children. What is to become of them? Why have you created a world in which you choose to be ‘powerfully powerless?’ I think you and your big plan absolutely suck. I think allowing vulnerable, defenseless children to be gang raped and thrown away, illiterate and unable to prevent and treat disease, is beyond a bad idea. The notion you are a God of justice is a savage lie. I think you’re a cruel charade and that you’re going to be bested by some God who doesn’t let crap like this happen

.

I thought about Archbishop Tutu. What would he say about all this? I send him an SOS in an email. A few days later, I received his reply:

God is so glad God has someone like you. Available, impotent, wanting, and willing, bearing an unbearable anguish, crying and offering all that you can, a point of transfiguration, offering, being a conduit of grace, of love, of tears, of impotence, and God will thank you for accepting the foolishness of the Cross, the weakness of the Cross. I love you and pray for you to go on being the caring, feeling, crying, weak centre of goodness in a horrible world …

My prayer was answered, and I remembered that God lives in the space between people, in relationships, is acted out through our interdependence. God had always been with me.

I remember what I believe: God is love, and when I love, God is with me; and, in order to love, I have to have someone to love. And that someone, well, maybe that someone is you, Ouk Srey Leak. And you, Farm Friend. And you, Solange.

As the dogs run ahead, I visit the ironweed, jewelweed, and admire the twining sprawl of passionweed, which looks like a crazy Costa Rican exotic even though it is our state’s wildflower. I kneel when “my” red tail hawk takes flight in front of me, keering. At the creek, I put my feet in the cold water and savor the delicious tingle and relief that swells in my entire body. I will rededicate myself to the Good God who made all this.

I wade a spell, the hem of my knee-length nightgown getting wet. However, I will not take off my gown, I will not swim. I want to keep the Congo on me. I do not want to rinse off where I have been.

I want to remember.