America's Prophet (24 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

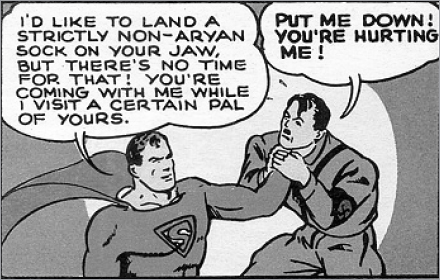

One expression of these writers’ Jewish point of view was their characters’ double lives—the awkward public self striving for accep

tance and the heroic private self that still felt the tug of the old country and hoped to defeat the perpetrators of evil. A number, including Superman, even took their battles abroad.

Superman battles a thinly disguised Adolf Hitler, as shown in

Look

magazine, February 27, 1940.

“The superheroes fought Hitler before the Americans did,” Weinstein said. “And coming from Jewish immigrants who are getting wrenching letters from home about their families, the effect is poignant.” In

Superman

number one, published in 1939, Clark and Lois Lane travel to a thinly disguised Nazi Germany, where Lois ends up in front of a firing squad, until Superman rescues her. In

Superman

number two, also from 1939, Clark Kent visits faux Germany again and meets Adolphus Runyan, a scientist clearly modeled on Adolf Hitler, who has discovered a gas so powerful “it is capable of penetrating any type of gas-mask.” The front cover of

Captain America

number one, published in March 1941, shows the hero smashing Hitler across the face.

“These writers are tapping into the stories they grew up with,” Weinstein said. “But even more, they’re tapping into their own frustrations with America and its inability to stand up for what’s right.”

Americans may or may not have noticed Superman’s Jewish identity, but Hitler sure did. As early as April 1940, Hitler’s chief propagandist, Joseph Goebbels, denounced Superman as a Jew. The weekly SS newspaper lambasted Jerry Siegel as “an intellectually and physically circumcised chap who has his headquarters in New York…. The inventive Israelite named this pleasant guy with an overdeveloped body and an underdeveloped mind ‘Superman.’” Goebbels went on, “Woe to the American youth, who must live in such a poisoned atmosphere and don’t even notice the poison they swallow daily.” And swallow they did: One in four American soldiers carried a comic book in his back pocket during World War II.

But while it makes sense that young Jews might identify with these superheroes, why did they resonate so much with Americans as a whole?

“Neal Gabler has a line in

An Empire of Their Own,

” Weinstein said. “‘The American Dream is a Jewish invention.’ It’s a profound idea, because once Hollywood, comics, and other pop media invent this idea, they help make it a reality.”

“But why isn’t Jesus part of this?” I asked. “Or David, or Abraham? Why is Moses the foundation of so many of these stories?”

“Because Moses is the greatest prophet,” he said. “And the story of Moses is the story of the hero. He’s weak. He’s fleeing his past. He can’t speak so well. Yet he becomes the greatest leader in the history of the Jewish people. If you look at any narrative—in film, theater—there’s an element of Moses in it. It’s the ultimate journey.

The hero starts out doubting himself—‘I can’t do it. I can’t be a leader.’ Yet he rises to the occasion and saves the day.”

“So if you think back to yourself as a boy,” I asked, “have you been saved by this story?”

He smiled. “The rabbis say that when Moses was standing at the burning bush, he saw in the fire all of the pain, all of the suffering that befell the Jewish people. And he also saw their greatness. That’s the dichotomy of Moses, and that’s the dichotomy of Clark Kent and Superman. And I think every one of us taps into that. Sometimes I’m standing at the pulpit, and I can’t connect. I feel nothing. But other times, I’m standing there and I

really

connect. I’m prepared. I’m spiritual. I feel like Moses the leader.

“The word for Egypt in Hebrew is

Mizraim,

” he continued, “which means ‘to constrict.’ Every one of us faces constrictions every day. We live in our own Egypt. Yet every one of us aspires to escape that. We can save the world.”

SAVING THE WORLD

was a central reason behind Cecil B. DeMille’s decision to remake

The Ten Commandments

in the 1950s. To help understand why, I went to see Katherine Orrison, a one-woman library of DeMille’s final creation. The fifty-something author has been obsessed with

The Ten Commandments

since she saw it as a nine-year-old girl in Anniston, Alabama. She eventually moved to Hollywood, befriended Henry Wilcoxon, DeMille’s longtime deputy who also acted in the film, and wrote two books about the movie. She also provided the commentary on the fiftieth-anniversary DVD. She lives in Hollywood in a home filled with overstuffed sofas, mountains of velour pillows, and multiple cats, along with never-before-seen mementoes, including a painting of DeMille and company in the Sinai.

As Orrison explained, DeMille chose to revisit

The Ten Commandments

because he was motivated by a desire to promote morality and religious freedom both at home and abroad. The director told guests at a luncheon in 1956, “I came here to ask you to use this picture, as I hope and pray that God himself will use it, for the good of the world.” In the conservative 1950s, Hollywood embraced the familiar, with westerns, musicals, and biblical epics all experiencing a revival. For six of the twelve years between 1950 and 1962, a religious historical epic was that year’s number one box-office draw, including

Quo Vadis, The Robe,

and

Ben-Hur

. Paramount had resisted DeMille’s entreaties to make another film about Moses, but his longtime rival, Adolph Zukor, an assimilated Hungarian Jew, overruled his staff. “I find it embarrassing and deplorable that it takes Cecil here—a Gentile, no less—to remind us Jews of our heritage! What was World War II fought for, anyway? We should get down on our knees and say thank you that he wants to make a picture on the life of Moses.”

“Zukor and DeMille had been like little dogs growling at each other for twenty years,” Orrison said. “The fact that Zukor ultimately backed the movie showed it was the right movie for the right time. Jews had almost been wiped off the face of the earth in the Holocaust. McCarthyism was rampant in Hollywood with the blacklist. The Cold War was raging. Everybody was scared.” She paused. “But DeMille wasn’t scared.”

A conservative in a town of liberals, DeMille used his film to promote his political views on everything from communism to race relations. In an extraordinary gesture, when moviegoers went to see

The Ten Commandments,

the curtains parted and DeMille himself appeared on the screen. “Ladies and gentlemen, young and old, this may seem an unusual procedure, speaking to you before the picture begins.” He went on to tell viewers what his movie was about. “The theme of this picture is whether men ought to be ruled by God’s law

or whether they are to be ruled by the whims of a dictator like Rameses. Are men the property of the state, or are they free souls under God? The same battle continues throughout the world today.”

In the midst of the Cold War, DeMille’s message was clear: Moses represented the United States; the pharaoh represented the Soviet Union. To drive home his point, DeMille cast mostly Americans as the Israelites and mostly Europeans as the Egyptians—Rameses II was Russian; Sethi I was English; Moses’ adoptive mother was Dutch. (Moses’ love interest, naturally, was American. No cavorting with the enemy!)

DeMille pressed his ideas in other ways throughout the film. The movie opens with a baby Moses being floated down the Nile, then being rescued by a daughter of the pharaoh. The Bible leaps immediately to an adult Moses discovering his heritage, but DeMille sexed up the story, adding a love triangle among Moses, his stepbrother, Rameses II, and Nefretiri, the throne princess. Moses is put in charge of building a treasure city, and he eases the workload of the Israelite slaves, though he doesn’t yet know he’s their kin. A jealous Rameses II tells the pharaoh that Moses must be the Hebrews’ deliverer. Moses then learns his heritage but announces he’s unashamed: “Egyptian or Hebrew, I’m still Moses.” At a time when many Jews still struggled with assimilation, Moses’ open embrace of his faith was a powerful statement of self-confidence.

Moses spends time among the Israelites and murders one of their taskmasters. Brought in chains before the pharaoh, Moses declares it evil that people are oppressed, “stripped of spirit, and hope and faith, all because they are of another race, another creed. If there is a God, He did not mean this to be so!” Again, the emphasis is on inclusion; God accepts all faiths, all races, all creeds. Rameses II banishes Moses to the desert and then marries a heartbroken Nefre

tiri. Moses also marries and is a peaceful shepherd in the desert until one day he spots a bush awash in flames. DeMille had become intrigued by a rabbinic commentary that said that the voice Moses heard from the burning bush was his father’s. In the scene, DeMille used Heston’s own voice slowed down and deepened. (When Moses receives the Ten Commandments, God’s voice is a mixture of Heston’s, DeMille’s, actor Delow Jewkes, and DeMille’s publicist, Donald Hayne. Perhaps one reason DeMille got such good press is that he allowed his publicist to play God!) Even more telling: When Moses speaks to God in the bush, DeMille omitted Moses’ words from the Bible that imply he was a stutterer. In the Hollywood of the 1950s, the hero did not stutter.

“They originally shot the burning bush scene in the Sinai,” Orrison said, “but they had to reshoot it in Hollywood because Charlton Heston couldn’t pull off modesty. He couldn’t do humble—

no matter what

. But the scene does work in the end. The Moses we get in 1956 from Charlton Heston is the way America wanted to think of itself at that time. The country’s no longer humble. The country’s a superpower. And it sees itself as God’s chosen place. So Heston becomes the profile on the coin that says

IN GOD WE TRUST

. That Rushmore visage. Now the hair is white, the beard is longer. He becomes a Founding Father—at least the way we were taught our Founding Fathers looked.”

The mixture of Hollywood magic and 1950s politics is perhaps best on display in the fan favorite of

The Ten Commandments

—the ten plagues. The Bible gives enormous weight to the plagues. Moses’ birth, adoption, flight into the desert, marriage, and firstborn son are all dispensed with in only one chapter of the text. The ten plagues take nearly seven. Moses’ brother, Aaron, directs the first three plagues—turning the water into blood, an inundation of frogs, and

lice. For a superpower so completely dependent on water for irrigation, transportation, and religious ritual, Egypt would have been traumatized by the attack on its water supply. But just when the pharaoh is ready to relent, his stubbornness returns. Moses takes over and pilots the next six plagues—insects, pestilence, and boils, followed by hail, locusts, and darkness. Again, for a culture in which the highest deity was the god of the sun, darkness would have been particularly devastating. “The Egyptians could not see one another, and for three days no one could get up from where he was; but the Israelites enjoyed light in their dwellings.” Pharaoh begs Moses to take his people and leave, but Moses insists that the pharaoh first make a sacrifice to God. The sides are at a standoff, and God announces plans for one final plague.

DeMille, working with primitive special effects, faced enormous challenges in converting the plagues into believable cinema. He chose to show only three: turning the water into blood, hail, and killing of the firstborn sons. For the blood, prop maestro William Sapp built a section of the Nile in a soundstage and stood in the river with a garden hose just beneath the surface. When Heston touched the water with his staff, Sapp pulled away the nozzle, causing red water to spew forth. DeMille found the first take too slow, so the next day Sapp turned up the pressure and pulled the hose away faster. For the hail, mothballs were considered too toxic and too fragile. So with Heston and Yul Brynner standing together in a Hollywood soundstage, Sapp and his colleagues huddled in the rafters with giant bags of popcorn. The kernels were perfect stands-ins because they could be easily swept up after each take. (Sapp also hand-made one hundred latex frogs with mechanical feet for another plague, and they taped Anne Baxter’s reaction, but her feigned horror was deemed over-the-top and DeMille managed to do what the pharaoh couldn’t: stop at least one infestation.)

In the biblical account, the final plague follows a celebration of the first Passover. God instructs each Israelite family to take a lamb, sheep, or goat and slaughter it at twilight. “They shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of the houses in which they are to eat it. They shall eat the flesh that same night…with unleavened bread and bitter herbs.” Moses instructs the Israelites to spread the blood with a hyssop branch and stay indoors until morning. God will see the blood, he tells them, and “pass over the door.”

In the film, Moses gathers his Hebrew family around an abundant table and celebrates a Passover meal. DeMille lingers over the scene, which includes the Egyptian princess who pulled him from the water and, in a bold political statement in pre–civil rights America, a band of black attendants. The Egyptians were left outside, Katherine Orrison stressed, where they would be exposed to God’s wrath; blacks were invited inside, where they were protected.