America's Prophet (25 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

The tenth plague was often portrayed in art as an angel with a bloody knife, but DeMille thought the image wasn’t scary enough. “The most frightening thing in the 1950s was the atom bomb,” Orrison explained. “Everybody was told that radiation could permeate every nook and cranny of every house or shelter. You couldn’t see it, you couldn’t smell it, you couldn’t feel it. But it could kill you.” Sapp came up with the idea of a green fog that swooped down out of the sky in the shape of a claw. The idea for the claw came from a menacing cloud formation one of DeMille’s secretaries had seen over the San Fernando Valley.

Did Americans understand the connection? “I certainly did,” Orrison said. “I’m a firstborn. I’m sitting in Anniston, Alabama, watching this movie, and I’m terrified.”

“Even as a child you thought it was radiation?” I said.

“You couldn’t get away from it. Remember, we were doing duck-

and-cover drills every week. I knew I wasn’t one of the chosen people. I was Episcopalian. But thank God Moses let those African slaves inside his house. Because what it said to me was you can be black, you can be white, you can be a nonbeliever, but Moses is a universal guardian. I think the reason baby boomers embraced the movie is that it spoke directly to our childhoods.”

“What I find fascinating about the Passover scene,” I said, “is that when Moses is in the slave quarters, he’s suddenly human. He’s not that wooden prophet who confronts the pharaoh.”

“Yes! Thank God! He’s the great father. The father of our country. And for me, as a child of divorce, he was

my

father.”

“Your father?”

“If I was going to live through what my parents were doing to me, I needed a surrogate parent. Divorce is no big deal now, but I was in a small southern town, and I was the only divorced child in my school. And I can remember the day my mother said, ‘Don’t tell anybody. You’ll lose your friends.’ And she was right. I lost all my friends.”

“But there were lots of people you could have latched onto as a father figure,” I said. “Why Moses?”

“I was the right age. And I thought, ‘God loves me, even though I’m not a Jew. If I can get into that house with Moses, I’ll be safe. I may not have a father, but Moses is everyone’s father.’”

“But why not Jesus?” I asked.

“Jesus couldn’t be my father. He was above me. Jesus was divine. Moses is a family man. He’s a leader. He was so real to me that the first Passover after I saw the movie, I went to our refrigerator, took out some lamb chops, and spread the blood on our front door.”

My jaw dropped.

“I’ve done it in every place I live,” she said. “I do it here!” And

with that she stood up, led me to the front porch of her Hollywood home, and pointed out two faint, reddish brown streaks on either side of her front door. I thought of Exodus 12: “You shall observe this day throughout the ages, as an institution for all time.” Moses was still alive in the Valley of Sin.

“So what did your mother think?” I asked.

“She said, ‘Kathy, we’re not Jewish.’”

“But you did it anyway.”

“I thought I needed to be saved,” she said. “I thought, ‘If I follow God’s law, and I listen to Moses, then my life will be okay.’ I wasn’t sleeping at night! Thinking about Moses was the only thing that brought me peace.”

CECILIA PRESLEY LIVES

in the desert, nearly three hours east of Los Angeles. After all the back-and-forth to get to her, she welcomed me to her lagoon-front home near Palm Springs as if I were an old friend.

Call me Ceci

.

How about a drink

?

Excuse me while I let out the dogs

. I wondered how honest she would be about the man she calls Grandfather, but I quickly discovered she had lost little of the spunk that had caused DeMille to have her chaperoned in Egypt. It didn’t work. She fell so hard for Abbas El Boughdadly, the cavalry officer hired to wrangle the horses and camels, that she married him and moved to Cairo. The news caused such a scandal that it was reported in

Time

magazine.

“It wasn’t a scandal in my family,” Presley said. “Of course they were sorry to see me go, but he was a marvelous man. It didn’t work. I shouldn’t have done it. Grandfather was my life. But when I came home after a few years, he said, ‘Now I can like Abbas again.’”

She eventually remarried, took over the family foundation fol

lowing her grandfather’s death in 1959, and became an ardent philanthropist and film preservationist. I was interested in whether her grandfather, whom Billy Graham dubbed “the prophet in celluloid,” was a religious man himself.

“God was alive to him,” she said. “The Bible was alive. But religion was not. He found it too narrow. He went to church, but he would go when they were empty and sit in them.”

“Was he one of those people who was a lifelong searcher?”

“His fundamental belief was that Jesus Christ was a messenger, but he never stopped searching. He was fascinated by scientists—from Edward Hubble to Albert Einstein. He was working on a film on space exploration when he died. To him, religion and science were not incompatible.”

“But if he was so interested in Jesus, why remake

The Ten Commandments

and not

King of Kings

?”

“Because Moses is a more universal story than Jesus, and in the fifties a more relevant story. Moses is the antithesis of communism, and Grandfather

hated

communism. He said terrible things happened to countries who had no god.”

I asked her if she thought those views were reflected in the film.

She looked at me stupefied. “It

is

the movie—from the beginning to the end. When Pharaoh enslaves his people, that’s communism. When he punishes at will, that’s communism. When he’s the divinely chosen king, that’s communism. You don’t have to spell it out. In fact, spelling it out would be preaching. But people pick it up.”

Just in case, DeMille did spell it out—in his introduction, in interviews, and, in an unprecedented move, in the streets of the United States. As part of his plan to spread biblical values, DeMille actually paid to put the Ten Commandments in public squares across the country. The idea had its roots in 1946 when juvenile judge

E. J. Ruegemer of Minnesota offered to suspend the sentence of a sixteen-year-old boy who had stolen a car if he promised to keep the Ten Commandments. “What are the Ten Commandments?” the boy asked. Working with the civic group the Fraternal Order of the Eagles, Ruegemer distributed 100,000 framed prints of the law of Moses around the country over the following years, along with 250,000 comic books that recount the story. DeMille heard about the effort while he was working on

The Ten Commandments

. He contacted the judge and offered to up the stakes. He then persuaded Paramount’s promotion department to pay for granite monoliths of the Ten Commandments to be placed on courthouse lawns, in city halls, and in public squares in every city where the film played. Over more than four thousand were made, and DeMille dispatched Heston, Brynner, and other stars to attend the dedications. One of these monuments, in Austin, Texas, later became the basis for the Supreme Court decision in 2005 that allowed the Ten Commandments on public property but banned them from courtrooms. A publicity stunt for Paramount became the basis of landmark U.S. law.

And the ploy worked.

The Ten Commandments

was released on October 5, 1956. Reviews for the three-hour-thirty-nine-minute film ranged from respectful to savaging. One critic tagged it “Sexodus,” another “epic balderdash.” The

New Republic

deemed it “longer than the forty years in the desert.” But audiences loved it. The film earned $34 million in its first year, second only to

Ben-Hur

for the decade. By 1959, it had been seen by 98.5 million people. Today, its inflation-adjusted total ranks fifth on the all-time box-office list, behind

Gone With the Wind

,

Star Wars

,

The Sound of Music

, and

E.T.,

and ahead of

Titanic, Jaws,

and

Ben-Hur

. When its annual network screening on Easter is calculated, it would easily be the most viewed film of the 1950s.

“And the letters we got!” said Mrs. Presley. “One man wrote Grandfather that he had been a Nazi prison guard in Poland and had beat a Jewish prisoner senseless. ‘See, now you look like the rest of the Jews who were in your Bible,’ the guard said to his victim. But when he saw

The Ten Commandments

and looked into the face of those Jews, the man wrote Grandfather for absolution.”

As this letter suggests, DeMille’s biggest impact may have been in the area of interfaith relations. The 1950s represented a breakthrough in America’s relationship with God, when the starkly drawn denominational lines of the past began to fade. True religion was under threat, wrote historian Will Herberg in his landmark 1955 study,

Protestant-Catholic-Jew

. Instead, religion had been replaced with what he called a watered-down “faith-for-faith’s sake” attitude, where “familiar words are retained, but the old meaning is voided.” Religion now meant little more than maintaining a positive attitude in life and believing in everything you do. Dwight Eisenhower became an emblem of this denuded devotion. America, he said, “is founded in a deeply felt religious faith—and I don’t care what it is.” Eisenhower’s 1953 inaugural parade was led by a generic “float for God.” In 1954 “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance; in 1956 “In God We Trust” became the national motto; in 1957 it was added to the back of the one-dollar bill, in between the two faces of the seal.

The Ten Commandments,

with its blend of Jewish and Christian themes, fit perfectly into this moment. Despite the Hebraic subject, the film is replete with New Testament references, from Moses saying after the burning bush, “He revealed his Word to my mind and the Word was God,” an echo of the Gospel according to John, to a delinquent Moses appearing before the pharaoh yoked to what appears to be a wooden cross, to the playing of “Onward, Christian

Soldiers” during the Exodus. The film reflects the larger merging of Christian and Jewish strands of American life into what came to be called the Judeo-Christian tradition. Though the phrase first appeared in 1899, “Judeo-Christian” did not become widely used until after the Holocaust as an expression of the two traditions’ shared values of morality, freedom, and law. In the 1952 speech where Eisenhower proclaimed America’s religious foundation, he explained, “With us of course it is the Jud[e]o-Christian concept…a religion that believes all men are created equal.”

As arguably the most influential film of the 1950s,

The Ten Commandments

both mirrored and molded the mainstream acceptance of different faith traditions that began to emerge in late-twentieth-century America. DeMille was decades ahead of his time when he included Islam in the list of great religions that belonged in the American public sphere. In the film, Moses repeatedly stresses the universality of God, who was “not the god of Israel or Ishmael alone, but of all men.” Ishmael is the progenitor of Muhammad and a central prophet in Islam. Also, DeMille had his cast and crew read the Koran and often said the strongest encouragement to make the film came from the prime minister of Pakistan, “who saw in the story of Moses, the prophet honored equally by Moslems, Jews, and Christians, a means of welding together adherents of all three faiths against the common enemy of all faiths, atheistic communism.” DeMille’s genius was to make Moses a projection not just of American strength but also of American pluralism.

I asked Ceci Presley how much DeMille’s interest in interfaith relations might have been influenced by learning later in life that his mother was Jewish.

“Grandfather identified with Judaism his whole life,” she said. “But with his father being a lay minister and having grown up read

ing the New Testament, he could no more have been a Jew than I could have been a Muslim. Still, he was far ahead of his time in so many ways, and the thing he hated most in his life was bigotry.

The Ten Commandments

is his attempt to show how America can save the world with a universal notion of God.”

That union of America, God, and Moses is most vividly displayed in the final scene of the film. Moses stands on Mount Nebo with his family, about to be summoned to his death. He blesses his

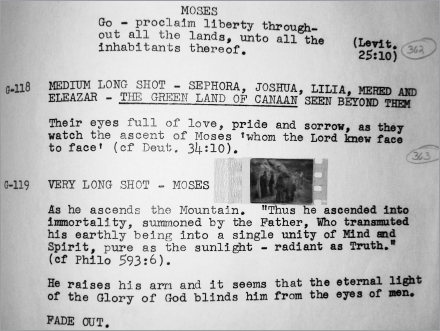

successor, Joshua, hands over the Five Books of Moses, then proceeds a few steps toward the summit. Then he turns, raises his arms to swelling music, and intones in his most sermonizing voice, “Go, proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.” The words inscribed on the Liberty Bell come not from this moment in Deuteronomy, of course, but from Leviticus 25. Yet DeMille understood their significance in American history. Noerdlinger’s research had uncovered not just the Mosaic connection to the Liberty Bell but also the story of Moses on the seal. A publicity illustration released with the film showed Charlton Heston holding up the Liberty Bell as if it were the Ten Commandments.

Close-up of the final scene of

The Ten Commandments,

as shown in Cecil B. DeMille’s private script, complete with cell of the finished film, in which Moses utters the phrase depicted on the Liberty Bell, from Leviticus 25:10: “Go—proclaim liberty throughout all the lands, unto all the inhabitants thereof” from the private collection of the Cecil B. DeMille Estate.

(Photograph courtesy of the author’s collection)