America's Prophet (8 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

Pharaoh sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his head and a Sword in his hand, passing through the divided Waters of the Red Sea in Pursuit of the Israelites: Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Cloud, expressive of the divine Presence and Command, beaming on Moses who stands on the shore and extending his hand over the Sea causes it to overwhelm Pharaoh.

The echo of the Exodus language widely used in America at the time is haunting. The committee’s report, submitted to Congress on August 20, 1776, offers vivid, behind-the-scenes evidence that the founders of the United States viewed themselves as acting in the image of Moses. Three of the five drafters of the Declaration of Independence and three of the defining faces of the Revolution—Franklin, Jefferson, and Adams—proposed that Moses be the face of the United States of America. In their eyes, Moses was America’s true founding father.

This news stunned me. Why hadn’t I heard about this before? Is it widely known? I sought out an expert. John MacArthur is a sixty-year-old historian from Oregon who grew interested in the seal as a teenager and has since collated every scrap of evidence and every representation. Faced with waves of conspiracies, he created a kind of Great Seal Anti-Defamation League at www.greatseal.com. I asked him if it was a coincidence that Franklin and Jefferson had both come up with Exodus imagery.

“We don’t know if they discussed it,” he told me, “but if they had, why did they come up with such different ideas? I get the impression it was independent.”

“Then why Moses?”

“He’s like an action hero,” MacArthur said. “He’s a role model. And they’re saying, ‘We’re doing the same thing he did. And God wants us to do it.’ That’s the key message: It’s God’s will. The motto ‘Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God’ evolves into the final motto,

‘Annuit Coeptis,

’ ‘Providence has favored our undertakings.’”

But Franklin and Jefferson are widely regarded as among the least religious of the Founding Fathers, and here they are proposing for the seal an act that shows God’s involvement in human history. “Jefferson later publishes a New Testament where he excises all the miracles,” I said, “yet this is the greatest miracle in the Hebrew Bible.”

“For them, slavery violates the rights of man,” he said. “So they view the Exodus as part of natural law, not religious. The Creator gave us life and liberty, so fighting for that freedom is a natural part of being human.”

After the frenzied rush to design the seal, the Congress, faced with a British invasion of New York that August, tabled the idea and didn’t take it up again until 1780. A second committee, made up of what MacArthur called “nobodies,” proposed an entirely new seal, with a seated goddess of liberty on one side and a heraldic shield on the other. That design was also put aside for several more years. A third committee submitted the final design on June 20, 1782. It has the American bald eagle holding an olive branch in one talon and a bundle of arrows in the other, with

E PLURIBUS UNUM

flowing from its beak. The only hint of the first design is the image of light “breaking through a cloud” above the eagle’s head. The reverse side depicts an Egyptian pyramid topped with the eye of Providence, also a legacy image.

“But why ditch Moses?” I asked. “If the later two committees were of nobodies, the first committee was made up of

three of the towering figures of the Revolution

.”

“I think those committees didn’t believe it was proper to have a human being on the seal,” he said. “Too much like the king. Seals are supposed to be more stylized.”

“But it’s worse,” I said. “Not only did they scrap Moses, they replaced him with a

pyramid

. It doesn’t take a Talmudic scholar to point out that we’ve gone from the Israelites being freed from slavery and the pharaoh dying in the Red Sea to the pyramid, which is the burial spot and tribute to the pharaoh, and which they probably (and wrongly) believed had been built by the Israelites when they were slaves. We’ve regressed.”

“The two words they used to describe the symbolism of the pyramid were

strength

and

duration,

” MacArthur said. “They chose it because it was thousands of years old and they wanted America to be strong and endure.” Also, he noted, Exodus imagery may have been appropriate for the liberation of 1776, but by 1782 the country was more focused on rallying around Washington and building an infrastructure. As for claims that the eye and pyramid are Masonic symbols, MacArthur said he had found little evidence that this influenced the design. “You don’t have to be a Mason to be fascinated by the pyramids.”

“So you’ve been looking at these proposals for forty years,” I said. “Do you wish they’d kept Moses?”

“I’ve actually written a screenplay in which Moses is the key to solving the puzzle.”

“So you’ve become Dan Brown!”

He chuckled. “The truth is, when I think of the seal today, I don’t see the dollar-bill version. I see the description. The true form of the seal is the written word that Congress adopted. Anybody can interpret that description. The seal is like the national anthem. It’s really just a piece of sheet music, and every musician makes a slightly different song from the same piece of music.”

BEFORE LEAVING PHILADELPHIA

, I went to stand in front of Independence Hall. Night had fallen and the crowds had thinned, leaving the crisp formality of the seventeen multipaned windows in front and the elegant tower above. With its state-of-the-art lighting and grand presence at the head of the mall, the building may be more arresting today than it was in 1776, when it was surrounded by taverns and dirt alleyways. Time and adoration have elevated it to its position as headquarters of American democracy.

Yet across the street, the Liberty Bell hangs suspended in its exquisite glass chapel, arguably upstaging its former home. The word

LIBERTY

faces the tower. I learned during my visit that Independence Hall receives around 750,000 visitors a year. The Liberty Bell, 2 million. More than just a symbol of 1776, the Old State House bell has become the global icon of freedom. Replicas have been erected over the years in Hiroshima, Berlin, and, in a fitting coming-home, Jerusalem, facing Mount Zion, in 1976. Whenever oppressed peoples march for emancipation, in places like Tiananmen Square or Soweto, they stride behind a Liberty Bell.

And it seems only fitting that a phrase from the Five Books would help shape this mascot of liberty. If the Hebrew Bible makes anything clear, it is that Israel should remember that God freed them from ancient Egypt. More than fifty times the Pentateuch uses a variation of the statement “Remember that you were slaves in the land of Egypt and the Lord your God redeemed you” (Deut. 15:15). The first sentence of the Ten Commandments repeats the idea, as does Leviticus 25. A similar thought is expressed more than one hundred times in the rest of the Hebrew Bible. In part because of this repetition, the Exodus emerges as the central event in biblical history.

It also becomes a defining event in the history of freedom itself. As German poet Heinrich Heine wrote, “Since the Exodus, freedom has always spoken with a Hebrew accent.” Since 1776, freedom has also spoken with an American accent in many places—and been visualized with the Liberty Bell. The union of the Exodus and 1776 in the form of the Old State House bell is a celebration of the idea that human beings can imagine a better life for themselves. As I was leaving Christ Church, Tim Safford told me a story that brought home this ideal and captured the unlikely path of Leviticus 25:10 from a forgotten verse in an unloved book of the Bible to the international expression of human dignity.

In July 1999 the archbishop of Cape Town paid a visit to Philadelphia and Safford volunteered to escort him around town. “Njongonkulu Ndungane had lived in the shadow of Desmond Tutu internationally,” Safford said, “but in South Africa, he was highly regarded because he had served on Robben Island with Nelson Mandela.” On his first night in town, as Safford was dropping the archbishop off at the hotel, Ndungane asked, “Is the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia?” Safford arranged a special tour, and the next day Ndungane arrived at the bell as a student was asking a Park Service ranger, “What is the meaning of the inscription?”

“Well, we don’t know exactly,” the ranger said. “It probably honors the fiftieth anniversary of the Charter of Privileges and has nothing to do with freedom—”

“All of a sudden, Ndungane interrupts him,” Safford said. “‘No, that’s not right,’ Ndungane says. ‘Leviticus twenty-five means that God will always free his people. Humanity corrupts itself and people get enslaved. So God makes a provision that every fiftieth year, you stop the economic hardship, you stop the political oppression, and you set everyone free and start again on an equal level. Because

no doubt in fifty years you will have messed everything up again. That’s why the Liberty Bell proclaims freedom. Because we will always have oppression, but God will always deliver us from it. There’s reason to hope.’”

The ranger stood flabbergasted, his mouth agape. The students were transfixed. After a minute, the ranger said, “Wow, you seem to know a lot about our bell. I’m not exactly sure if that’s true…”

Archbishop Ndungane replied, “On Robben Island, we always dreamed it was true.”

A MOSES FOR AMERICA

T

HE VERY WORSHIPFUL

Geoffrey Hoderath stepped to the pulpit of Saint Paul’s Chapel in lower Manhattan. To his right was a painting commemorating the survival of the chapel on 9/11. Around him was the oldest public building in continual use in New York City, dedicated in 1766. Behind him rose a dazzling gilded altarpiece depicting Mount Sinai in clouds and lightning, the Hebrew name for God, Yahweh, in a medallion, and the two tablets of the Ten Commandments. And this was a church, not a synagogue. Hoderath was wearing a blue suit, a red tie, and a white lambskin apron.

“On behalf of the Grand Lodge of the State of New York, Free and Accepted Masons,” he announced in a tone that suggested he was reading the Decalogue to the Israelites at Mount Sinai, “I welcome you to this reenactment of the inauguration of George Washington as the first president of the United States, on this the anniversary of that historic event. Our purpose is to honor the father of our coun

try, to commemorate the founders of our great republic, many of whom were Freemasons, and to proclaim our living heritage as a free nation.”

The two hundred or so Masons, including many in tricorne hats, blue coats, and breeches, applauded. I had slipped uninvited into this ceremony after nearly a year of trying to penetrate the elusive and secretive world of Freemasons. Every time a door would crack open, two more closed before me. Letters went unanswered. E-mails went unresponded to. Phone messages went unreturned. When I heard about this event, I decided to take my chances. I was attempting to probe the enigmatic web connecting the Masons, the Bible, and the building of America. More, I was hoping to get a closer look at a hidden treasure of the founding era, the Masonic Bible that Washington used to take the oath of office. The Bible lay at the heart of a centuries-old riddle about the passage where the president rested his hand.

I was also trying to unravel the deep-seated bond that connected the leading prophet of the Israelites with the first president of the United States. From the night he led the Continental Army across the Delaware in 1776 to his leadership of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 through his death in 1799, Washington was compared to Moses. In some ways the analogy was understandable. The War of Independence, with its vulnerable, ragtag population pitted against a much stronger, military superpower, had deep parallels with the Exodus. As the reluctant leader trying to hold together an anxious population and lead his people out of subjugation and into freedom, Washington was the natural heir to the Mosaic longings of Americans.

But in the years that followed the Revolution, the analogy would seem less appropriate. Moses, I expected, would have retreated into

semiretirement in America, like Washington. Instead, the opposite happened. Having sounded the bell for Revolution, Moses became the clarion for the Constitution. Having offered the road map for freedom, he became the model for imposing strict federal law. Why? What is it about Moses that once more made him such a necessary presence in the volatile first decade of American life? And what does it say about the identity of early Americans that they viewed the founding leader of the Israelites and the patriarch of the United States as such analogous leaders?

“As we gather to reenact one of history’s most momentous events,” Hoderath continued, “let us begin as they did, by invoking the aid of the Great Creator of Heaven and Earth. On that day, Thursday, April 30, 1789, the rector of Trinity Church offered the invocation, which Washington himself had composed. ‘Almighty God, we make our earnest prayer that thou will keep the United States in thy holy protection…’” Hoderath continued to the end of the short prayer, then uttered, “Amen.” As he did, a fife-and-drum corps paraded down the nave.

“If ever history knew an indispensable man,” Hoderath continued, “George Washington was that man. When the thirteen colonies needed leadership in the War of Independence, the Continental Congress chose Washington. When liberty seemed lost in the fall of 1777, Washington kept the soldiers in the field. When independence lapsed into sectional conflict after the war, the framers asked Washington to chair the Constitutional Convention. And when the new republic elected its first president, again the natural choice was Washington.”

As Hoderath suggested, the period immediately following the Revolution proved to be one of disarray. The Articles of Confederation were ineffective; Congress was impotent; Europe jeered.

Washington complained that thirteen states all ruling independently would soon ruin the whole. “What astonishing changes a few years are capable of producing,” he wrote. Distraught, Americans searched everywhere for answers—science, philosophy, the classics. But many viewed the crisis as a moral one and turned to the Bible for guidance. “This revolution,” one delegate to Congress said, “has introduced so much anarchy that it will take half a century to eradicate the licentiousness of the people.”

For many Bible lovers, the Exodus appeared to provide direction. As the story of the Israelites in the desert suggested, maybe the way to secure freedom was to give up some freedom. Maybe what was needed was a firm leader and firmer law. Maybe, one Boston preacher said, the United States needed a national charter that would leave a glow upon the nation like that “upon the face of Moses when he came down from the holy mountain with the tables of the Hebrew constitution in his hand!”

And so the narrative resumed. The Constitutional Convention would play the part of Mount Sinai—and Washington would be Moses.

“As a young man beginning his career of greatness,” Hoderath continued, “Washington was made a Freemason in Virginia. His lodge still meets in Alexandria. Later, when serving as president, Washington was the worshipful master of that lodge. In that regard, he was like many of the nation’s founders who were ardent Freemasons. Today, Freemasons around the world take pride in our early brothers’ contributions to the new nation and to the cause of freedom.”

Hoderath then set the stage for the inauguration. “More than two hundred years ago, everything we see around us in lower Manhattan was entirely different.” Trinity Church had yet to be rebuilt following the fire that swept through the city in 1776. The Canyon of

Heroes, the section of Broadway later devoted to ticker-tape parades, was a street of fashionable houses. The meeting under a grove of buttonwood trees that led to the New York Stock Exchange was still several years away. Yet the city’s population was 33,000, more than that of Philadelphia or Boston. Its size and centrality contributed to its being chosen the first capital.

Washington personally oversaw every detail of his installation. After learning of his election while in Mount Vernon on April 14, the general paid a final visit to his ailing mother, then proceeded by coach toward New York, switching to horseback in some towns to lead parades spontaneously organized in his honor. He recrossed the Delaware under a triumphal arch supported by thirteen pillars and surrounded by women and children dressed in white. From New Jersey, he traveled via water on a red, white, and blue barge, manned by thirteen pilots in white. As he entered New York Harbor, twenty singers rowed up alongside him and regaled him with a version of “God Save the Queen”:

Joy to our native land!

Let ev’ry heart expand

For Washington’s at hand

With Glory crown’d!

On the morning of April 30, thousands flocked to the old city hall on Wall Street, which had been renovated and rechristened Federal Hall. Washington proceeded to the second floor to meet with the House and Senate. Careful to leave his military uniform behind, he was clad “in a full suit of dark-brown cloth of American manufacture, with a steel-hilted dress sword, white-silk stockings, and silver shoe-buckles. His hair was dressed and powdered in the fashion of

the day.” As one observer wrote, the great man seemed agitated and nervous “more than ever he was by the levelled cannon or pointed musket.” Outside, the roofs of the houses were crowded, and the throngs were so dense “it seemed as if one might literally walk on the heads of the people.” All eyes were focused on the balcony. “In the centre of it,” one observer wrote, “was placed a table, with a rich covering of red velvet; and upon this a crimson-velvet cushion.” The stage was set for the inaugural swearing-in of the president of the United States.

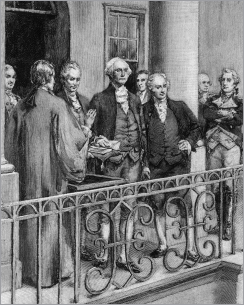

George Washington being inaugurated with his hand on Genesis 49-50 of a Masonic Bible, Federal Hall, New York, April 30, 1789. Colored engraving, 19th century.

(Courtesy of The Granger Collection, New York)

But there was a problem. Washington had nothing to rest on that

cushion. There was no Bible. The Constitution does not require taking the oath of office on a Bible. John Adams had not used a Bible when he was sworn in as vice president nine days earlier. But the Bible’s role in oath taking goes back as far as Augustine, and incoming kings and queens in Britain had taken their coronation oaths on Bibles for centuries.

For the most part, Washington was not particularly religious. Historian Joseph Ellis called him a “lukewarm Episcopalian and a quasi-Deist.” Even religious scholar Michael Novak and his daughter Jana, who argue in

Washington’s God

that the president believed in the Hebrew notion of God, conclude that he wasn’t exactly a Christian. He never took Communion; he rarely knelt during prayer; he did not use Christian names for God such as Redeemer or the Trinity; and in decades of private correspondence he referred to Jesus only once or twice.

But he did believe in Providence, a deity that acted in history to free the Americans from bondage under the British. As he stated in his Thanksgiving Proclamation of October 1789, all Americans must unite in rendering unto Almighty God “our sincere and humble thanks for His kind care and protection of the people of this country previous to their becoming a nation.” Four years later, after Benedict Arnold’s treason was uncovered hours before he did serious damage, Washington wrote that the providential train of circumstances “affords the most convincing proof that the Liberties of America are the object of divine Protection.” And Washington clearly knew his Hebrew Bible. In a letter to the Jews of Newport, he acknowledged the shared roots of Jews and Christians: “May the Children of the Stock of Abraham who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants.” His decision to be inaugurated with the Bible under his fingers and the Constitution on his lips guaranteed that these two achievements of the

written word would be linked in the office of the presidency for generations to come.

Geoffrey Hoderath picked up the story. “After consulting with Washington, Chancellor Robert Livingston, the Grand Master of Masons of the State of New York and one of five drafters of the Declaration of Independence, who was to administer the oath of office, hurriedly sent Worshipful Brother Jacob Morton to nearby Saint John’s Lodge to retrieve its altar Bible. Washington might have been playing a clever game. There were twenty-three churches in New York City. If he were to swear on a specific Bible, that church might get precedence. Instead he used a Masonic Bible, which is nondenominational. We are fortunate to have that Bible here today.”

Hoderath gestured to the right of the pulpit, where three men in suits, aprons, and Secret Service demeanors stood holding a square metallic suitcase. With its shiny faces and bulging locks, the case looked like the kind of device James Bond might use to carry a portable satellite dish, a machine gun, and a spillproof container of shaken vodka martinis. The men put on white gloves and opened the top. They pulled out a sizable King James Bible, with a flaking leather front and two locks on its side. It had been printed in London in 1767 by Mark Baskett, the same printer who published the Book of Common Prayer that Jacob Duché defaced on July 4, 1776.

The Washington Bible, as it came to be called, is the most illustrious Bible in the country, and arguably the most famous single book in American history. At least four other presidents used it in their inaugurations: Warren Harding, Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter, and George H. W. Bush. The Masons carried it to Washington, D.C., in 2001 for the inauguration of George W. Bush, but rain prevented its use. The Bible was present at the funerals of Andrew Jackson and

Zachary Taylor and was used at the dedication of the Washington Monument, the laying of the cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol, and the centennial celebration of the White House and Statue of Liberty. The Bible is owned by Saint John’s Lodge and is used in Masonic rituals, though it spends most of its time on display at the Federal Hall museum on Wall Street, a onetime customs house built on the spot of the demolished first capitol. A gallery contains the original balcony railing and the purported slab where the president stood. I had visited Federal Hall a few months earlier and stumbled onto the tale of how the Bible was nearly destroyed one morning two centuries after it first gained fame.

At 7:45

A.M

. on September 11, 2001, janitor Daniel Merced showed up for work at Federal Hall, less than a thousand feet from the World Trade Center. A first-generation Hispanic American, Daniel asked his colleague to sweep the building’s front steps, and then he went to change. Just before nine o’clock, Daniel looked out the door and noticed the steps were covered in office paper, fax-transmittal forms, and debris. It was a jolt. “Didn’t you sweep the steps?” he asked his colleague. Stepping outside, he cried out, “Look, there’s smoke!” Daniel thought 120 Broadway was on fire and rushed to find his cousin, who worked there. Along the way he ran into a colleague, who told him, “A plane hit the World Trade Center.” They hurried back to Federal Hall, and as they got inside, the building shook. “‘Lock the doors,’ our supervisor said. ‘Another plane hit the World Trade Center.’ At that point we knew what it was.”