America's Prophet (5 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

I asked if the quotation suggested Norris and his colleagues viewed themselves as a continuation of the Israelites.

“I doubt they considered themselves chosen like the Israelites,” she said. “I think they looked on themselves as Englishmen, first and foremost, and that they were entitled to the rights of Englishmen. Winthrop, Bradford, and others in the seventeenth century viewed themselves more as exceptional. By the eighteenth century, people were more practical. The idea that the Bible portrays oppression, and everybody knows the text, made it easy for them to quote the Bible.”

AS SOON AS

we stepped through the door and into the bell tower I began to sweat. The first two floors are air-conditioned, the others are not. A worn wooden staircase leads to the third floor, an unfinished space that reminded me of the attic in my childhood home. In

the building’s early years, Diethorn explained, the State House employed a doorkeeper, who cleaned the fireplaces, lugged wood, and replaced the candles. This floor was his living quarters. “In the late eighteenth century, the doorkeeper’s wife had a baby in this room,” she said. The next level up, the fourth, is where the bell ringer would have stood—Philadelphia’s Quasimodo. This floor is where Isaac Norris’s ill-fated bell spent much of its life, inactive and trapped.

Norris’s request for a bell arrived in London in the spring of 1752 and was quickly relayed to Whitechapel Bell Foundry. The foundry cast the bell using the customary method of an inner mold, called the core, and an outer mold, called the cope, into which the founders poured molten bell metal, an alloy of 77 percent copper and 23 percent tin, mixed with traces of arsenic and gold. “Basically, it’s like a fruitcake,” Diethorn said. A bell has five parts: the lip; the sound bow, where the clapper strikes; the waist, the concave part in the middle; the shoulder, which is where the Leviticus quote is located; and the crown, which connects the bell to the wooden yoke. The note Norris’s bell sounded was an E-flat.

The bell arrived in Pennsylvania that September, and eager workers made a critical misstep: They hurriedly unpacked the bell, mounted it on a temporary rigging, and bolted in the clapper. They pulled back the metal clapper, dropped it toward the lip, and listened intently as a deadly thud reverberated through history. The bell cracked. A horrified Norris blamed Whitechapel for using metal that was “too high and brittle.” Whitechapel, in turn, blamed “amateur bell-ringers.” Wars have been launched over less. Norris tried to send the bell back, but the ship’s captain refused to transport it, so Norris dispatched the bell to “two Ingenious Work-Men” in Pennsylvania, Charles Stow and John Pass, who melted it down and recast it. Tinkering with the alloy, they added an ounce and a half of copper for

each pound of bell, yet another miscalculation. The following April they lugged the recast bell to the top of the tower for a ceremonial chime. Instead of a sonorous peal, the bell issued an atonal

bonk,

which one witness described as the sound of two coal scuttles being banged together. Far from proclaiming liberty throughout the land, the bell couldn’t be heard on the ground floor.

Stow and Pass were so humiliated by the “witticisms” hurled at them that they hurriedly prepared for a second recasting. “If this should fail,” Norris wrote, “we will…send the unfortunate Bell” back to Whitechapel for remolding. A frantic six weeks later, the recast bell was ready to be toted to the belfry. This version at least rang, but its sound pleased few. “I Own I do not like it,” Norris wrote, and ordered a replacement from Whitechapel. He planned to return the original bell for credit, but the assembly ultimately kept both. The “Old Bell” hung in the tower, while the “Sister Bell” hung in a secondary cupola on the fourth-floor roof where it tolled the hours. The Old Bell was still hanging in the State House steeple in July 1776, though the tower was so rotted it was dangerous to enter.

The drama of that summer was marked by four key dates: July 2, when the Congress voted for independence; July 4, when it adopted Jefferson’s document; July 8, when the Declaration was read aloud for the first time; and August 2, when most members signed. The only date for which evidence exists of bells being rung in the city is July 8. “There were bonfires, ringing bells, with other great demonstrations of joy,” wrote a witness. But no one specified that the State House Bell was among those sounded, and there’s reason to at least be skeptical, considering the poor state of the belfry. Five years later the tower was considered so rickety it was removed entirely and the bell retired to the fourth floor, where it remained mute for the next forty years and was rung only on ceremonial occasions. Twice offi

cials actually sold the bell, but both times they balked before handing it over. For all practical purposes, Pennsylvania’s E-flat bell was impounded, a forgotten slave to its own misfortune, unable to peal even for its own release. (The Sister Bell was also removed, in 1828, when the new bell tower was finished. It was given to a Catholic church, which was burned in 1844 in a wave of anti-Catholic riots. The bell crashed to the floor and broke into smithereens. Workers collected all the pieces they could find and recast them into a 150-pound bell, down from the original 2,080 pounds. The recast version now hangs at Villanova University.)

During one of the original bell’s ringings, likely in the 1820s or 1830s, it cracked again. Some witnesses claimed the cracking occurred on the visit of Marquis de Lafayette in 1824; others said it followed the passage of the Catholic Emancipation Act in Britain in 1829; still others suggested it was at the funeral of Chief Justice John Marshall in 1835. The truth, Diethorn explained, is that the bell was probably cracking all along, just not visibly. On Washington’s Birthday 1843, the crack had become so substantial that it rendered the bell unusable. Officials performed a repair technique called stop drilling, in which they actually removed chunks of metal to prevent the jagged edges from scraping, thereby creating the inch-wide gap that became the bell’s most distinctive feature. The rounded edges from this procedure are still visible. At the time, officials actually took the metal fragments and made them into trinkets, which they sold. “It was like buying a piece of Noah’s ark jewelry,” Diethorn said.

So why such misfortune?

“In effect, the bell was doomed from the start,” she stressed. “They were taking the same metal, subjecting it to heat, breaking it down, and reconstituting it. Plus, their casting techniques were highly flawed. Today, they use sterile environments and humans don’t get anywhere near the bells when they’re being cast.”

I asked her why the bell came to have such meaning.

“It’s hard to get your heart around a building,” she said. “But the bell is timeless, in its shape, its function. It’s easier to understand on an emotional level.”

And so much of that emotion, she added, comes from the inscription. “You have to remember, the cultural identity of these people is so vividly informed by the Bible,” Diethorn said. “It’s not the same as saying they were religious, but it was the common language of all members of that society. What I think is fascinating about this era is how the idea of reason, science, and objectivity, which inform the Enlightenment so completely, can coexist in their minds with the idea that there is a divine presence in the world.

“I think a lot of laypeople in America today feel that the Enlightenment was somehow antireligious,” she continued. “That people like Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, and others were deists and didn’t believe in God. That couldn’t be further from the truth. The language of religion is so ingrained in their culture in the form of the stories, the aphorisms, the proverbs, and the characters, and this religious language is readily adopted as the language of liberty, whether you’re talking about the Israelites, their captivity, and their freedom, or leaders like Moses, David, or Solomon. The eighteenth century is big on parallels. They’re searching for historical precedent for their own actions, and they’re finding it in religious rhetoric because everyone understood and could relate to that.”

“And it seems that specifically what they were looking for is authority,” I suggested. “An authority higher than the king. God gives you that authority.”

“The heart and the head need to be equally stimulated to make something worth doing,” Diethorn said. “The Enlightenment may give you intellectual credibility, but the Bible gives you emotional credibility.”

THE STAIRCASES IN

the tower get wobblier the higher you climb. Above level five, you enter the new tower, installed during the building renovation in 1828. When the nation’s capital moved to Washington and the state capital to Harrisburg, the State House was slated to be torn down, but a wave of nostalgia accompanied the visit of Lafayette and the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Ceremonies inspired by the French hero’s arrival introduced the name Independence Hall into popular use.

The sixth flight of stairs is by far the most narrow, and the steps are placed at uneven intervals. About halfway up, they are interrupted by jutting steel girders that now buttress the structure. I had to lift my hands above my head and squeeze between the railing and the beam, like climbing through the pistons in a car engine. And then the stairs stop. The only way to reach the cupola is via a wooden ship’s ladder. This seventh level is dark and much smaller than those below it. The air is stale and dusty, more like descending into a dungeon than ascending to a summit. I grasped the rungs and began to climb.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the fractured, largely forgotten, nearly century-old State House bell suddenly experienced a remarkable renaissance resulting from a newfound fascination with the Mosaic phrase on its face. In 1839 a Boston abolitionist group called Friends of Freedom circulated a pamphlet that featured on its cover an idealized drawing of the bell, including the inscription

PROCLAIM LIBERTY TO ALL THE INHABITANTS

. The drawing was captioned “Liberty Bell,” and inside was a poem “inspired by the inscription on the Philadelphia Liberty Bell.” Six years later another abolitionist group adopted the same image in a poem by Bernard Barton.

Liberty’s Bell hath sounded its bold peal

Where Man holds Man in Slavery! At the sound—

Ye who are faithful ’mid the faithless found,

Answer its summons with unfaltering zeal.

The emphasis on the newly coined Liberty Bell was part of the abolitionists’ desire to deflect attention away from the Constitution that had enshrined slavery into law and to return attention to the Declaration and its ideal of liberty for all.

The notion soon took hold among Americans. Benson Lossing’s popular

Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution,

published in 1850, featured a brief history of the Liberty Bell. The account included the fictitious story of a blue-eyed boy who waited outside the Assembly Room on July 4, 1776, heard the passage of the Declaration of Independence, and scurried up the bell tower to the “gray-bearded” guard crying, “Ring! Ring!” The story had been circulating for a decade and quickly became accepted fact. To capitalize on the new popularity, officials in 1852 carted down the bell from the rafters and placed it on display along with a portion of George Washington’s pew from Christ Church, a Bible from 1776, and Ben Franklin’s desk. As Mayor Robert Conrad said at the dedication, “We acknowledge even a profounder feeling of exultation over the contacts and deeds that have made this the holiest spot—save one—of all the earth; the Sinai of the world, upon which the Ark of Liberty rested.”

Completing its resurrection, the Liberty Bell began traveling around the United States. It made seven journeys by rail between 1885 and 1915, for a total of 376 stops in thirty states, including world’s fairs in Chicago, New Orleans, and Atlanta. Three of the four first trips were in the South, where Northerners tried to use the bell as an instructional tool to enlighten former Confederates. Stereopticons

showed former slaves bowing down to the bell. John Philip Sousa wrote “The Liberty Bell” march. Along with renewed interest in the Stars and Stripes through Flag Day and the Pledge of Allegiance, the Liberty Bell became part of a wave of American exceptionalism, which held that God had chosen America to lead the world into a new Promised Land. As another Philadelphia mayor, Charles Warwick, put it in 1895, “No religious ceremony in the bearing of relics could have produced more reverence than this old bell.”

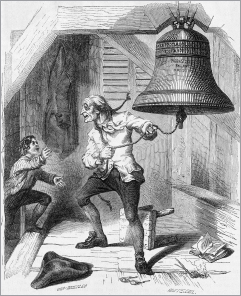

“The Bellman informed of the passage of the Declaration of Independence,” depicting the mythical story of the ringing of the Liberty Bell. From the cover of

Graham’s Magazine,

June 1854.

(Courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia)