America's Prophet (6 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

Transferring the Liberty Bell from truck to train at St. Louis after the Exposition, 1905.

(Courtesy of The Library of Congress)

And by rallying so intently around the words of Leviticus 25, Americans were reaffirming their commitment to the country’s moral foundations and its roots in the Hebrew Bible. During the years when the Liberty Bell was assuming its stature, Americans had near-universal biblical literacy, which means that most people would have recognized the context of the inscription. They would have seen it as part of God’s larger call to free the enslaved, salve the sick, uplift the poor. That recognition didn’t mean Americans went rushing to change their public policy, but it did mean they wanted their greatest symbols to be associated with their highest aspirations.

And sure enough, successive waves of ostracized Americans attempted to commandeer the Liberty Bell to support their own liberations. Suffragettes molded a replica of the Liberty Bell, dubbed “the Justice Bell,” to promote women’s rights, chaining the clapper until women could vote. Civil rights leaders made pilgrimages to the bell, and in 1963 Martin Luther King, Jr., invoked its symbolism in his jubilant phrase “Let freedom ring” at the March on Washington. During the Cold War, Jewish groups laid a wreath at what they deemed the “Bell for Captive Nations” to promote the plight of Soviet Jewry. And as early as 1965; gay-rights groups marched at the bell calling themselves “our last oppressed minority.” The process was like a form of Liberty Bell midrash, with each minority group

proclaiming liberty unto itself. More than any other emblem of 1776, the Liberty Bell had become the embodiment of America.

AT THE TOP

of the ship’s ladder is a small trapdoor. I pushed it open, hoisted myself through the narrow opening, and suddenly found my head in the mouth of a giant bell. The cupola is an octagon, with narrow arches open to the air. Some wasps had built a nest inside the bell. The Centennial Bell, dating from 1876, is considerably larger than its ancestor, weighing thirteen thousand pounds in honor of the thirteen colonies. Its metal is a mixture of American and British cannonballs from Saratoga and Union and Confederate cannonballs from Gettysburg. Around its lip is the inscription

PROCLAIM LIBERTY THROUGHOUT ALL THE LAND UNTO ALL THE INHABITANTS THEREOF

.

After the oven of the tower, the open air of the cupola felt freeing. The ground floor of this building may have given birth to the prose of America, but this was a place of song. I could see all the way down the expanse of Independence Mall, a beautification begun in the 1950s, and up the Delaware River, where, thirty-nine miles upstream, Washington crossed on Christmas night in 1776. For the first time on my climb, I felt proud. I rested my hand on the lip of the bell, which felt cool and vibrated with the slightest touch. I was so accustomed to thinking of the Liberty Bell in its climate-controlled museum across the street, I was jolted to remember that the bell had lived for decades on top of this building.

Karie Diethorn joined me in the cupola. For a second her academic mien melted away. She smiled ruefully. I asked her if she had ever experienced a personal moment with the bell.

“I’m always awestruck with how people react to it,” she said. “Once we did a military swear-in. The navy brought sailors and they

took their oaths in front of the Liberty Bell. It was extremely moving. They committed themselves to serving their country in front of one of its greatest icons. To them, the Liberty Bell embodied all the sacrifices that came before them. I didn’t expect to be as overwhelmed as I was.”

“So why do you think people need that object?”

“I think it symbolizes hope. In the 1950s a lot of people looked at the Liberty Bell and thought about America as the greatest country in the world. Now, we still see the patriotic story, but we also see the incredible tragic events of our history. The irony of slavery and liberty coexisting in our nation. The Liberty Bell embodies all of those ideas. It’s a very flexible symbol. I think that’s why people relate to it.

“Also, the message is very poignant,” she continued. “That inherent in our history is tragedy and victory simultaneously. From slavery comes freedom. But freedom is easily lost and can become slavery again. To me, it’s like looking down a long hallway, and the Leviticus verse resounds throughout that hallway for whatever period you’re in.”

“I love how it comes back to sound.”

“Hearing is our most fundamental sense,” Diethorn said. “Even a deaf person can feel vibration. And it’s the same with this place. The bell is the most important part of this otherwise public building. It’s the universal part. It sings the Declaration of Independence. The smallest part of the building turns out to have the biggest voice.”

IF THE CUPOLA

atop Independence Hall is one of Philadelphia’s most glamorous spots, the basement of the Christ Church parish house is surely one of its dingiest. It’s cramped, poorly lit, and overflowing with books, the kind of room where some Dickensian waif

would be locked away during his childhood. The rector of the church took me into that morass and showed me one of the least known artifacts of July 4, 1776, and one of the most stirring relics I’d ever held.

Christ Church was always something of a twin of Independence Hall. The two were built within months of each other, in the same formal Georgian style. When its own bell tower was completed in 1754, Christ Church was the tallest building in the colonies, a distinction it held until 1810, the longest any structure has enjoyed that honor in American history. The front door was lorded over by a three-foot-high relief of Charles II, with garlands and a toga in the manner of Julius Caesar, yet George Whitefield was invited to preach here. Christ Church was a royal building but open to change. And with bells, it superseded its crosstown twin: The State House had one; the church had eight.

“The reason this church was the largest building in the colonies was to send a message,” explained Tim Safford, the nineteenth rector. With his WASPy good looks and staunch commitment to social justice, he could be the poster preacher for the contemporary Anglican Church. He is also a voracious student of the Revolution. “And the king was the ruler of the church. What happened in the State House was fine, but not until it happened in the church did independence hit home. That’s why Jacob Duché was such a hero.”

Jacob Duché was the rector of the most important church in America at a time when the most important Americans sat in his pews every Sunday. His father had been a mayor of Philadelphia, and the Duchés were descended from Huguenots, antiestablishment French Protestants. “He’s steeped in the intense cauldron of Philadelphia,” Safford said, “where blacksmith is living next to banker, banker next to seamstress, and they all meet in Christ Church. Only in Philadel

phia could Betsy Ross sit next to the president of the United States in church, even though she could afford only a cheap pew.”

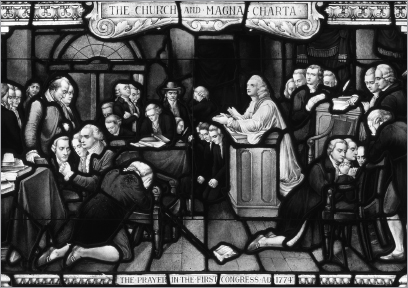

Stained-glass window at Philadelphia’s Christ Church depicting the Reverend Jacob Duché’s reading of Psalm 35 at the first Continental Congress, Carpenter’s Hall, 1774.

(Courtesy of Christ Church, Philadelphia; photograph by Will Brown)

That diversity threatened many of the delegates who gathered in Philadelphia on September 6, 1774, for the first Continental Congress. The meeting was held at Carpenter’s Hall, around the corner from the State House. A lawyer from Boston motioned that the assembly open with a prayer, but delegates from New York and Charleston objected. The members were simply too divided by religious sentiments, with Episcopalians, Quakers, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians among them. Samuel Adams suggested they invite Duché, who he had heard was a “Friend to his Coun

try.” The next morning Duché, dressed in clerical garb and white wig, read that day’s appointed psalm from the Book of Common Prayer, the thirty-fifth. “Plead my cause, O Lord, with them that strive with me: fight against them that fight against me.”

“I never saw a greater Effect upon an Audience,” John Adams wrote his wife, Abigail. “It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that Psalm to be read on that Morning.” But then Duché did something even more extraordinary. He deviated from the prescribed Anglican readings and, in homage to the revivalist spirit of the time, offered what Adams called “an extemporary Prayer, which filled the Bosom of every Man present. I must confess I never heard a better Prayer or one so well pronounced…. It has had an excellent Effect upon every Body here.”

“This was the ultimate Great Awakening moment,” Tim Safford said. “Many of the delegates just fell to their knees and began to cry. The antiauthoritarian spirit of the Awakening had suddenly been transported into the command center of the Revolution.”

But Duché’s revolutionary fervor reached its climax, along with that of the rest of the city, on July 4, 1776. That Thursday afternoon, after the Congress had approved the Declaration of Independence but before the text had been printed, signed, or read aloud, Jacob Duché strode to Christ Church and convened a special meeting of the vestry. The members unanimously agreed that Duché could strike out all homages to the king from the Book of Common Prayer. The minutes of that meeting are stored in this basement room and were the first book Safford pulled from the shelves to show me: “Whereas the honourable Congress have resolved to declare the American Colonies to be free and independent States, in consequence of which it will be proper to omit those petitions in liturgy wherein the King of Great Britain is prayed for as inconsistent with the said declaration.”

Safford then reached to the uppermost bookcase and pulled out a particularly clean cardboard box, tied with a ribbon. He laid it on the table, opened it, and removed a maroon leather book, about sixteen inches tall and ten inches wide. Considering its age and the poor conditions in the room, the book was in remarkably good condition. He opened to the title page.

The Book of Common Prayer, and administration of the Sacraments and other rites and ceremonies of the Church according to the use of the Church of England.

It was printed by Mark Baskett in 1716. “I get goose bumps every time I hold it,” Safford said. “This was the physical manifestation of the king. And to Duché, the king was God.”

Safford slowly turned the pages of the mammoth book and pointed out the half dozen passages where Duché had crossed out references to the Crown and replaced them with tributes to the new country. Duché scratched through words that asked God to bless “thy servant George, our most gracious king and governor,” and wrote in by hand, “the Congress of these United States.” He excised parts of a prayer beseeching God on behalf of “this kingdom in general, so especially for the high court of Parliament under our most religious and gracious King,” and inked in “these United States in General, so especially for the delegates in Congress.” He drew a line through entreaties for the “prosperity and advancement of our Sovereign and his kingdoms,” and inserted the “honour and welfare of thy people.” In half a lifetime of reading American history, I had never seen an artifact that more vividly captured the epic transformation that day represented. And this gesture would not have taken months to sink in. Worshipers at the most powerful church in the land would have heard it that Sunday, July 7, the day

before

the Declaration of Independence was read aloud for the first time. Christ Church rang the true bell of liberty.

“I think this book represents Christ Church’s way of blessing

what happened over at the State House,” Safford said. “The Congress has gone and done this. What could be more helpful than to have Christ Church say, ‘We agree.’ Almost every other church was loyalist or refused to participate in the Declaration. And speaking as a priest, I can say that it was Duché who had to live with the consequences of what he did.”

“So what was he thinking at that moment?”

“I think he’s probably scared to death. I think he’s excited. I think he’s worried he might be hanged. I think he believes he’s doing God’s work.” Safford lifted his head as if toward some invisible authority and clenched his hands as if to build up courage himself. He wasn’t really speaking to me now. “And I’ve always thought this was the real Mosaic moment of the Revolution. Duché must have felt like Moses, going before the pharaoh. How could you do anything but quake? Every molecule in your being had trained you to believe that the king was the king because God had put him there. Duché was denying everything in his heart. And the only way you can do that is if you believe that God has called you to do it.”

Safford turned back to look at me. “And I’m sure his agony is the agony of all Moseses in American history. He had all the anguish that Dr. King had in 1968. He had all the doubt that Abraham Lincoln had. He had all the concerns of George Washington.

Is this the right thing?

”

Duché’s torment only increased in the next year as the American cause suffered a series of debilitating blows. Finally, in September 1777, when the British conquered Philadelphia, one of their first acts was to arrest Jacob Duché. A night in jail shook the preacher, as did Washington’s bloody defeat the following week at nearby Germantown. On October 8, Duché wrote Washington an eight-page private letter begging him to call off the war. “He

is saying, ‘George, I know you. Put an end to this before it becomes a travesty,’” Safford said. “‘The British are going to destroy you and slaughter these young men. Congress is leading you astray.’” But Washington found the letter a “ridiculous, illiberal performance” and released it to Congress. Duché, the hero of 1776, was finished, forced to seek exile in England. Years later he returned to Philadelphia a broken and forgotten man, buried in an unmarked grave.