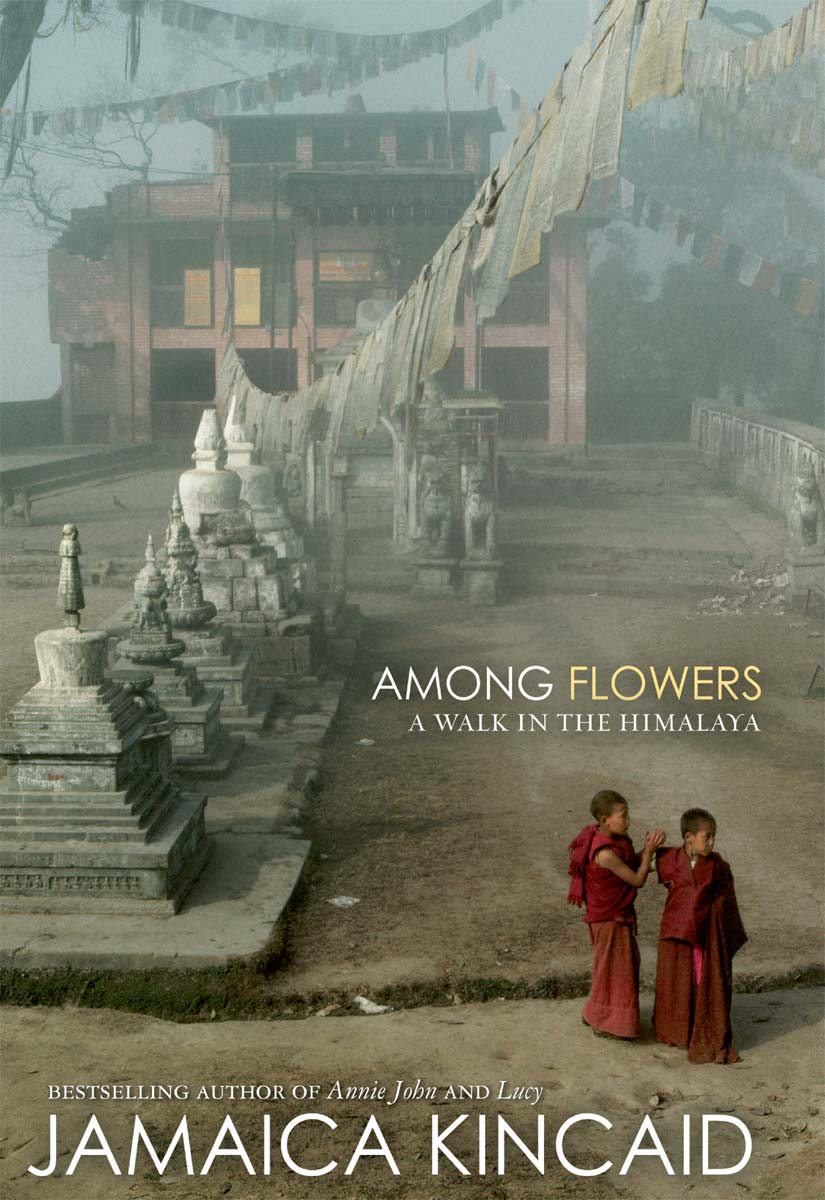

Among Flowers

Authors: Jamaica Kincaid

Mr. Potter

Talk Stories

My Garden (Book)

My Brother

The Autobiography of My Mother

Lucy

A Small Place

Annie John

At the Bottom of a River

A W

ALK IN THE

H

IMALAYA

AMAICA

K

INCAID

For Jonathan Galassi

Published by the National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-4688

Text copyright © 2005 Jamaica Kincaid

Map copyright © 2005 National Geographic Society

Photographs by Daniel J. Hinkley

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the National Geographic Society.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kincaid, Jamaica

Among flowers: a walk in the Himalaya / Jamaica kincaid.

p. cm. -- (National Geographic directions)

ISBN: 978-1-4262-0901-7

1. Kincaid, Jamaica--Travel--Nepal. 2. Nepal--Description and travel. I. Title. II.

Series.

PR9275.A583K5632 2005

813'.54--dc22

2004059284

One of the world's largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations, the National Geographic Society was founded in 1888 “for the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge.” Fulfilling this mission, the Society educates and inspires millions every day through its magazines, books, television programs, videos, maps and atlases, research grants, the National Geographic Bee, teacher workshops, and innovative classroom materials. The Society is supported through membership dues, charitable gifts, and income from the sale of its educational products. This support is vital to National Geographic's mission to increase global understanding and promote conservation of our planet through exploration, research, and education.

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463), write to the Society at the above address, or visit the Society's Web site at

www.nationalgeographic.com.

O

ne day, in the year 2000, I was asked to write a book, a small one, about any place in the world I wished and doing something in that place I liked doing. I answered immediately that I would like to go hunting in southwestern China for seeds, which would eventually become flower-bearing shrubs and trees and herbaceous perennials in my garden. Two years before, in 1998, I had done this. I had accompanied the most outstanding American plantsman among his peers, my friend Daniel Hinkley, and some other plantsmen and botanists on a plant-hunting and seed-collecting adventure in Yunnan and Sichuan Provinces. I started out in the city of Kunming and it was so hotâI wondered if I was just going to have a look at things I could grow in a garden that I made on the island in the Caribbean where I grew up. I wondered if the most thrilling moment I would remember was seeing the tropical version of

Liriodendron tulipifera

, the tulip tree, of William Bartram's travels. But then we went out in the countryside, and up into the mountains, up to fourteen thousand feet in altitude, Dan now reminds me, and I collected seeds of species of primulas,

Iris

, juniper, roses, paeony,

Spiraea, Cotoneaster, Viburnum

, some of which I have now growing in my garden.

I experienced many difficulties in this adventure, but they were of a luxurious kind. I did not like, and could not even bring myself to understand, my hosts' relationship to food: I feel that the place in which it is taken in, eaten, be it the kitchen or the dining room, must be far removed from the place, bathroom or outhouse, in which it comes out again in the form of that thing called excrement. Not once was my life really in danger, not even when I was close by to places where the Yangtze River was in the process of flooding over its banks just at the moment I was driving by its banks in my rather nice, comfortable bus. The greatest difficulty I experienced was that I often could not remember who I was and what I was about in my life when I was not there in southwestern China. I suppose I felt that thing called alienated, but it was so pleasant, so interesting, so dreamily irritating to be so far away from everything I had known.

And so when I was asked to do something I liked doing, anywhere in the world, my experience in southwestern China immediately came to mind. I called up Dan Hinkley and I said to him, Let's go to China again. As a plantsman and botanist, and nurseryman to boot, Dan goes to some faraway place and collects the seeds of plants once or twice a year. The intellectual curiosity of the plantsman and botanist needs it, and the commercial enterprise of the nurseryman needs it also. When I suggested southwestern China to him as a place of adventurous plant-collecting, he said, Oh, why don't we do something really exciting, why don't we go to Nepal on a trek and look for some

Meconopsis

? Why don't we do something really interesting, he said.

In October 1995, Dan had traveled to Nepal on his first seed-collecting expedition there. He had collected in the Milke Danda forest, a forest that is in the Jaljale Himal region.

Milke Danda, Jaljale Himal!

To see those words on a page, flowing from my pen now, is very pleasing to me. In 1998 when I accompanied Dan and some other plants-people to southwestern China, I had no idea that places in the world could provide for me this particular kind of pleasure; that just to say the name of a place, to say softly the name of a place, could cause me to long deeply to be in that place again, or to long just to be nearby again. That first visit he made to Nepal haunted Dan so that he wanted to go there again. It's quite possible that I could hear his longing and the haunting in his voice when he suggested to me that we go looking for seeds in the Himalaya, but I cannot remember it now. And so Nepal it was.

We were all set to go in October 2001. Starting in the spring of that year, I began to run almost every day because Dan had said that the trip would be arduous, that I had no idea how hard it would be, and that I must prepare my body for the taxing physical test to which I would subject it. And so I ran for miles and miles, and then I lifted weights in a way designed to strengthen the muscles in my legs. It was recommended to me that I walk with a backpack full of stones, so that I might make my upper body more strong. I did that. And Dan had said that I needed a new pair of boots and that I should break them in, and so I wore them all the time, in the garden, to the store, or even to a dinner outing. Everything was going along well, until near the end of August: I suddenly remembered that my passport with a visa stamped in it from the Royal Nepalese Consulate General in New York had not come back from my travel agent. I called to tell her that she ought to hurry them up because I applied for my visa in June and here it was August, and still I had not heard if I would be allowed to enter that country in a month. She was very surprised to hear from me, she had not received my passport in June, she had forgotten all about me. In any case where was my passport? We could trace its arrival in her office on Park Avenue, but it never reached her desk. It has been lost, she said; it has been stolen by someone in her office, I thought.

I applied for and within a matter of days received a new passport; I applied for and within a matter of days received a visa to enter and exit Nepal. I had myself inoculated against diseases for which I had not known antidotes existed (rabies) and against diseases I had not known existed (Japanese encephalitis). I felt all ready to go and then there came that new State of Existence into being called “The Events of September 11.” How grateful I finally am to the uniquely American capability for reducing many things to an abbreviation, for in writing these words,

The Events of September 11

, I need not offer a proper explanation, a detailed explanation of why I made this journey one year later.

The following spring, the spring of 2002, I resumed my intense training. I trained so hard that near the end of June I was limping, I had done something to my right foot, something that did not show up on an X-ray, only my foot hurt so very much. Then for a short period of time, my son, Harold, who was thirteen at the time, and I determined that he too would make the trip, yes, he would go to Nepal with me, but by the end of August we could see that was not to be. Dan sent me an e-mail asking for our passport numbers and other documents; he wanted to forward them to our guides who would then secure for us our internal travel documents. At that moment Harold said, No, he would not go, as if the whole idea was ludicrous in the first place. Later I would have many opportunities to be glad for his decision. I wrote back to Dan: “So sorry about all this. Harold is not coming but you probably guessed that. Tickets and documents only for me, then. We will share a tent. By the way: Have you heard of the plane crashing and the bus going off the road in the floods, all in Nepal? This happened yesterday. My love to you and Bob.”

Just around then, Dan's friends, two botanists who are married to each other and own a very prestigious and famous nursery in Wales, where they live, decided to join us. I have always been so envious of the many seed-collecting trips Dan had made with them to Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and China. Their names are Bleddyn and Sue Wynn-Jones, and the number of times I have heard Dan say that he and Bleddyn and Sue collected something together would fill me with such envy because I really always want to be someplace where seeds are being collected, I want to be in the place where the garden is coming into being. Their presence made me happy and when Dan said, in one of his e-mails, “This is going to be an adventure,” it made me forget, for a flash of time, the trouble I was having leaving. This account of a walk I took while gathering seeds of flowering plants in the foothills of the Himalaya can have its origins in my love of the garden, my childhood love of botany and geography, my love of feeling isolated, of imagining myself all alone in the world and everything unfamiliar, or the familiar being strange, my love of being afraid but at the same time not letting my fear stand in the way, my love of things that are far away, but things I have no desire to possess.

I left my home in the mountains of Vermont at dawn one morning at the beginning of October. Nothing was out of place. I made note that the leaves were late in turning, but when I look at a record I keep of things as they occur in the garden I see that I always think the leaves are late turning. It was warm for an early morning in early October, but it is so often warm in early morning in early October. And yet as I drove away from my house, I had the strange sensation that I might be seeing everything in the way I was seeing it for the last time, that when I saw again those things that I was looking at that morning, the mountains (the one I can see from my house, Mount Anthony, in particular), the trees, the houses, the people in their cars, the very road itself, they would not look the same, that the experience I was about to have would haunt many things in my life for a long while afterward, if not forever.

It was only after I returned home a month later that I noticed how quiet and clear are the streams and rivers near where I live; how calmly they meander along as if their paths are old and dull, their origins nearby, not hidden deep within some still unfamiliar place beneath the surface of the earth. Only then I noticed too how smoothed out the sides of the mountains were, not rippling with ridges; how almost uniform in height they seemed, gentle slopes, soft peaks, old and known, with no parts of them unexplored. And the sky above all this? Again, only when I returned home did I notice that the sky above me hardly ever caused me to observe it with real anxiety, being mostly clear and a sad pale blue in the daytime and turning to a grayish black at night. If I made particular note of water, land, and sky when I returned home, it is only because when I was away, walking in the foothills of the Himalaya, that became the world I knew. I knew with certainty. There, I lived outside all that time; and the distinctiveness of it all, the wide and open spaces, were especially so when seen from far away and protected by an overarching and concavelike sky. And this wide-open space was then pursued by the unrelenting encroachment of the mountains, this landscape in the Himalaya.

I left my home on a morning in early October and headed to the airport, which was four hours away. At the time, feeling that it was ridiculously false and then again not so at all, I insisted to myself that everything I saw I was seeing for the last time. This turned out to be true, for when I saw all that I had been familiar with again, everything was changed in my eyes, and yet it did remain the way it had always been, only that I did not see anything the same way again.

I left my home, I went to an airport in New York. I arrived there in the middle of the day. The airport seemed deserted, or spare of human emotion, or just unsettling in a chemically induced way, but I had not ingested a chemical of an unusual kind, as far as I knew. I got on the airplane. All the time my state of mind was influenced by the hard fact that my thirteen-year-old son had not wanted me to go away. That he had said goodbye to me with tears rolling down his cheeks; that he had, days before, asked people he thought could influence me, to tell me outright, my going away to this place, for such a long time, would cause him to suffer. I love my children, more than I love myself, and yet there I was on an airplane off to Hong Kong and then to Nepal.

On the way to Kathmandu, I spent less than twenty-four hours in Hong Kong; and this small amount of time had the feeling of being a particle of some sediment in a bottle that was being shaken up. Oh, the whirl of it. I was not here or there or anywhere. I was at the airport, again, and the flight was eight hours late. I was sent to a part of the airport where people with destinations different from mine were waiting. A modern airport is not unfamiliar to me. I have been in one of them many times, waiting to go from one place or the other. In a modern airport you will suddenly be confronted with people who are very different from you even though you are all wearing the same sort of clothes, and who have very different ideas from you about how the very world in which you place step after step ought to be arranged. I am used to that. But even so in Hong Kong, in the airport, I felt strange: alone, lonely, excited, happy, afraid, despair, all at the same time. These feelings were exaggerated when I got on the plane, Royal Air Nepal, and was told that the time was not an hour ahead, or an hour behind, but that the time was measured by the quarter hour. It meant that while I could calculate the rest of the world based on that thing called the hour being behind or ahead of me, when I was in Nepal fifteen minutes was lost or gained one way or the other. How confusing is such a thing, how magical is such a thing, how correct is such a thing. Though I only know all of this in retrospect, in sitting at my desk in Vermont and thinking about it, in looking back. We flew to Kathmandu in the dark of night. I childishly asked if it was safe to do so, wondering if we might accidentally crash into a mountain. We landed safely and I gave a man forty American dollars for carrying my suitcase from the baggage area to the taxi. Everyone was astonished by this amount of money, but I was so grateful to be myself, whatever that was, in one place that I would have paid many times that more just to say, “Hi, I am me.” I went to bed and slept soundly through the night in a memorable hotel called the Norbu Linka, memorable because it is the only place I have slept in Kathmandu.

That next morning Dan took me to have my photograph taken for my trekking visa, which is a separate one from my visa to enter Nepal, and he also took me to a store to buy an elegant walking stick, a walking cane made of native wood that had the head of a dog carved at the top, just where your hand gripped it. At another store, we bought chocolate bars and tins of candy. Then we went to the best bookstore in the worldâthat is if you are interested in the world of explorationâthe Pilgrims Book House, and I bought a book, just for the sake of buying a book, about the first attempt to climb Kanchenjunga. Until that moment I did not know there was a mountain called Kanchenjunga. All that time, I was still in between the things I had left behind in Vermont, my thirteen-year-old son not wanting his mother to go so far away from him, the flat-top mountains, the certainty of, just for instance, the plumbing situation (here is the kitchen, here is the bathroom, the two do not know the other exist). Dan had been in Kathmandu for some days before me and he had sent me an e-mail in which he said it was very hot, so bring suitable clothes. Many days before that he had sent me a long list of suitable clothes I would need for our walk in the mountains where we would gather seeds. This particular e-mail made me bristle with anxiety, but anxiety is never any help at all, and so I took note of it and then ignored it. Dan had titled his e-mail “I'll do your bras if you do my underwear,” and he'd written: