Among Flowers (4 page)

Authors: Jamaica Kincaid

I cannot tell now exactly when in those first few hours of the morning on my journey that my understanding of distances collapsed. I walked through the town of Tumlingtar and the way out led to a sharp incline and then to a set of houses surrounded by cultivated plots that seemed to be resting on a plateau, level ground, but the ground was never level for long, and suddenly, or eventually, I was climbing again, going up and up, and the going up seemed sudden, surprisingly new, for I had not expected it. For those first few hours, I was expecting the landscape to conform to the landscape with which I was familiar, gentle incline after gentle incline, culminating in a resolution of a spectacular arrangement of the final resting place of some geographical catastrophe. But this was not so. I walked up toward a ridge, and I thought that when reaching the ridge my whole being would come to something, the something that had made me there in the first place. But this was never to be so. The Himalaya destroys notions of distance and time, I thought then, plant-hunting destroys all sorts of notions, but this I have always known.

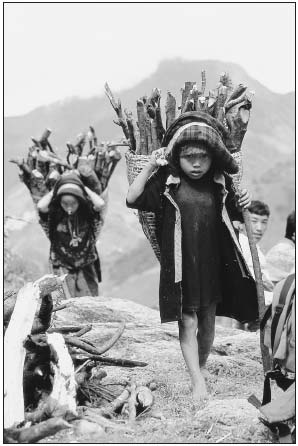

Nepalese gathering

Rhododendron,

their primary fuel source

The road then, sometimes as wide as a dirt driveway in Vermont, sometimes no bigger than a quarter of that, was red clay unfolding upward; the top of each climb was the bottom of another. By midmorning my senses were addled. It took me many days to realize, to accept really that I was going up; it took me many days to understand how far up

up

was, how there was no real up, how going up was just a way of going there. I began to have a nervous collapse, but fortunately there was no one in my company, botanist, Sherpas, and porters, to whom I could make my predicament matter. Dan had told me of the practice in Nepal of planting two

Ficus

trees together,

Ficus benghalensis

and

Ficus religiosa,

providing shade for the traveler, who from time to time turns out to be people like us. We passed by three such plantings and stopped to drink water, and then at the fourth one we stopped for lunch. As we walked we had been accompanied by a band of children, though not the same ones all the time. As some of them left, others would take their place. When we stopped for lunch, they crowded around and stared at us in silence. They watched us as we ate our lunch. It felt odd but also seemed fair: we were in their country looking at their landscape after all. That day, our first day of stopping to eat lunch, began with cups of hot orangeade, a drink that seemed then extravagant and unnecessary, tasting so hot and sweet, but later we would come to count on and look forward to it. According to the watch I wore on my left hand, a watch that was equipped to do all sorts of things that I could not make sense of, tell direction for one, it was ninety-six degrees and we were in the full heat of the sun all the time we walked. Sue had been walking with her umbrella open, shading herself. When in Kathmandu she had told me about bringing along an umbrella, I had secretly thought it an unnecessary thing to do; now I saw why and I could only look at her with envy.

We continued on our way that afternoon, the scenery remaining the same as the morning, except we came upon a family who lived in a small house that was in the shade of a huge citrus tree, a tree with fruits larger than grapefruits. At about half past one we came into Khandbari, a town that had telephones connected to the world from which I had just come. I called my son, Harold, spoke not to him but to someone who could say to him that I had called him, and went from feeling pleased with myself for that to feeling sad because I had not been able to tell him that I loved him myself. By that time, it was less than a week since I had been away from my home, but I began to wonder what exactly separated me from their memory of me. I was not dead, but might I as well be? Still, might-as-well is different from the certainty.

We passed through Khandbari and almost got into trouble because Dan had left his passport in Kathmandu and Khandbari had a checkpoint. I saw Sunam, our lead Sherpa and guide, speaking to a man in military uniform with an intensity and rapidity I had only seen in movies, and so had thought invented for presentation in a theatrical situation, but it worked in the same way; we were allowed to go on. We reached the place where we would spend the night, a village called Mani Bhanjyang, but the best spots had been taken by the two groups of trekkers who were on our same route. They were going to Makalu Base Camp, and we were on the same route as they for the next two days. Sunam found a place for us to camp down from that in the middle of a field, the only other level piece of earth in the vicinity. We were thirty-seven hundred feet up and even then the sky was beginning to be darker and more curved than I had ever known it to be. That night, I called Harold on my satellite phone and spoke to him directly.

It was that next morning that I began to see the flora of Nepal. We had left our campsite at half past six in the morning and started walking toward what, I did not know yet. It was ninety-six degrees by seven, according to the watch I wore, and we walked up and up for two hours straight. In fact we were just walking through, and also just walking toward, the end of our journey, but I did not know this yet. I still had the idea that we would walk to something and then leave it for something else. But that was never so. We were walking, and every place we walked was something, every place we walked was important, certainly from the point of view of a gardener. It was just that this gardener lives in Vermont. In any case we were walking, and it was very warm and I kept my eyes closed, in a way, because the climate I was walking in was not the climate in which I make a garden. The climate in which I was walking, the things growing there would count as annuals for me. As a gardener, I have a fixed view of annuals. They really are ornamentals. That is, they are ornaments for the more substantial and, so, really real perennials. In any case, we were walking and I was with Sue. For Dan and Bleddyn had raced ahead as would always be the case, and suddenly I saw these pink flowers everywhereâat my feet when I looked down and somewhat above eye level when I looked up, and then alongside me when I was just going forward. I recognized them from shape and texture, only I had seen them in another color, deep purple. I had seen those same flowers in a nursery in Vermont and in a garden in Maine but only in deep purple. To see them now in pink while remembering them in purple enhanced my feeling of anxiety and alienation, and so when I said to Sue, “What is this?” and she answered me matter-of-factly, “That's

Osbeckia

,” I was comforted.

The plant I had seen in the nursery in Vermont and in my friend's garden in Maine had a dark fleshy-colored and coarse-skin stem with deep purple flowers. I had always wanted to plant them in my garden, but they seemed as if they were not really annuals, they seemed too late-blooming and too woody in stem for my climate. On the whole, in my garden (and all the time I was walking around in Nepal I was mostly thinking of my garden) annuals need to be delicate-looking, while at the same time bearing flowers non-stop as if they do not know how to do anything else. Now as I trudged along, not knowing really where I was going, I was thinking of something I had known in passing, a plant seen in a nursery, and in a garden in Maine, trying to latch on to it as if it were one of the certainties in the whole of life. Much later I learned that the deep purple form of

Osbeckia

comes from Sri Lanka, the one before me was native to the place in which I was seeing it.

That day we walked eight miles going gradually uphill. We stopped for lunch in the middle of a village and I asked for a cola soft drink, and received it. That was the last time such a thing happened. It was then that I began to notice this phenomenon. I saw a girl, about the same age my daughter was then, seventeen, combing the hair of someone else with much carefulness; she was combing through her familiar's thick head of straight hair because it was riddled with lice. This was all done with a loving fierceness, as if something important depended on it. The person combing the hair used a comb that was fine-toothed and carefully went through the hair again and again, making sections and then dividing again the sections into little sections. This engagement between the delouser and head of hair made me think of love and intimacy, for it seemed to me that the way the person removed the lice from the head of hair was an act of love in all its forms. I saw this scene over and over.

That day, for lunch, the vegetable was something I knew by the name of “christophine” and which was familiar to Sunam by another name in Nepali. It is a soft, fleshy, watery fruit originating from somewhere I do not know but is used as a vegetable by people who come from the tropical parts of the world. It is not grown in Antigua, the island in the Caribbean where I am from, but it was grown on the island of Dominica, the island my mother is from. This vegetable was a staple of her diet when she had lived there, and I was remembering the lengths to which she would go to find it and incorporate it in my diet. I hated it then, and so imagine my surprise to find it for lunch in a small village in Nepal. It was the most delicious thing I ever tasted.

From the place we ate our lunch, the center of a little village full of people and many of the things that come with them, I could see ahead of me, my way forward, a landscape of red-colored boulders arranged as if deliberate and at the same time the result of a geographic catastrophe. I was making this trip with the garden in mind to begin with; so everything I saw, I thought, How would this look in the garden? This was not the last time that I came to realize that the garden itself was a way of accommodating and making acceptable, comfortable, familiar, the wild, the strange. Above us were some large brown rocks and they seemed firmly placed. So strange, I thought, How would I get to them? I thought, Once I got to them, I thought, Life would be settled, I thought. Much to my surprise, I walked up to them and was in them, and found a place to take a pee and then walked some more into a forest of gingers (

Hedychium

) in flower, skullcaps in flower,

Osbeckia

in flower,

Euphorbia

in flower,

Arisaema

in flowerâand the botanists, Dan and Bleddyn, especially were sad. They were not just sad, they began to sulk, and Dan complained to me about all that walking (two days) with no seeds to collect and Bleddyn complained to Sue (his wife) that there were no seeds to collect. We were only two days out, Sue said to Bleddyn. I said to Dan, We were still in the tropics. But they knew that. The day was hot. Sue had held her umbrella over her head, protecting herself from all that heat, and I wished again and again that I had brought one with me.

The forest of gingers was actually a swath of cultivated farmland. People were farming spices, for local consumption, and when I found this out, their guarded and circumspect relationship to me did not seem so inexplicable. While walking through this forest of the gingers I saw

Dicentra scandens, Agapetes serpens,

an epiphytic rhododendron,

Begonia, Strobilanthes

(blue and white), a yellow impatiens that Bleddyn said was not gardenworthy,

Philodendron, Monstera deliciosa, Hydrangea aspera

(subsp.

Robusta,

Bleddyn said to me),

Tricyertis maculata, Arisaema tortuosum, Amorphophallus bulbifera, Osbeckia

. Except for

Dicentra scandens

(the yellow-flowered climbing bleeding heart) and

Begonia

âthough not this particular oneânone of the plants were familiar to me.

At half past three in the afternoon we reached the village of Chichila. We had started the morning in Mani Bhanjyang at about four thousand feet and had walked up two thousand feet to Chichila. It was still hot but the clouds were coming in from Makalu, or so I was told, because if the clouds had not been coming, I would have been able to see the great Makalu, a mountain that I had never even heard of until I was nearing Chichila and every passerby greeted me with the word “

Nemaste

” and then “

Makalu

.” But we were not going to Makalu. We were going to look for flowers, or rather the seeds of flowers. Walking around the the village I saw little gardens in which were cultivated squash, corn, marigolds, and dahlias. We sat on a public bench in the hot sun and drank some beer we had bought. There was no other way for that beer to be had other than someone carrying it from Khandbari on his back. I had not seen, so far, animals put to this use. We had just started to enjoy how nice it was to sit with a beer in the hot sun after a day of walking up when, suddenly, without warning, it turned cold and windy and rain started to fall. It was as if, suddenly, we were in another day altogether, another day in another season. We moved into the shop where we had bought the beer and sat near a fire that seemed to have been burning all along, as if the people there knew that no matter how hot it got outside, eventually a fire would always be needed inside.