Among Flowers (7 page)

Authors: Jamaica Kincaid

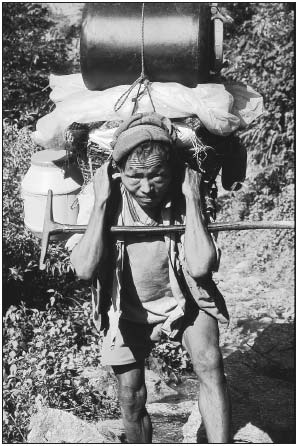

Porters' loads can exceed one hundred pounds.

Between the cows and their herdsman and Cook not finding water to cook us supper, we grew irritable. From our place way up above the village, and even from that way up above the place where we had eaten our lunch, we were closed in. The sun was setting somewhere; we could see the light growing dimmer, literally like someone turning the wick of a lamp lower. We, and by that I mean me in particular and especially, began to whimper and even complain. For one thing, from our vantage point, so high above, we could see the porters carrying our baggage and the tents and all our other supplies and necessities, resting at the place where we had eaten our lunch. So if Cook should find a place in which to cast camp, and casting camp always depended on him, weâand we were so important we felt thenâcould not enjoy camp, for the things that made sitting in camp comfortable were half a day's walk away. What had the porters been doing all day? someone saidâmeaning, What had they been doing when we were exploring the landscape, looking for things that would grow in our garden, things that would give us pleasure, not only in their growing, but also with the satisfaction with which we could see them growing and remember seeing them alive in their place of origin, a mountainside, a small village, a not easily accessible place in the large (still) world? We were then having many emotions, feelings about everything: The Maoists were right, I felt in particular: life itself was perfectly fair, people had created many injustices; it was the created injustices that led to me being here, dependent on Sherpas, for without this original injustice, I would not be in Nepal and the Sherpas would be doing something not related to me. And then again, the Maoists were wrong, the porters should be fired; they were not being good porters. They should bend to our demands, among which was to make us comfortable when we wanted to be comfortable. We were very used to being comfortable, and in our native societies (Britain, for Bleddyn and Sue; America, for Dan and me) when we were not comfortable, we did our best to rid ourselves of the people who were not making us comfortable. We wished Sunam would fire the porters. But he couldn't even if he wanted to. There were no other porters around.

We were hungry and tired. It really was getting dark. The sun was going away, not setting. We couldn't see it do that, we could only see the light of day growing dimmer. Still, we could see the porters. They were far away. Way below us. The most forward of them were not even near the place where we had come across the fragrant

Convolvulus.

And there was no real place to camp. No doubt I will always remember this evening, for it was the evening where we could not decide where we would stay, among other things. At just about the time some of the porters were traversing the unpleasant landslide, Sunam decided that we would cast our camp at a spot that was the only level site in the area. Cook had found a stream nearby, in any case, and that was always the deciding factor. We were three-quarters of the way up a steep rising of rock covered with some

Taxus

and

Sorbus

and, instantly recognizable to me, barberry and some kind of raspberry

(Rubus).

We made our way through them and found we were in a field that had growing in it mostly wormwood, some kind of

Artemisia.

What a relief. And then someone pointed out a leech and then another and then another, and we soon realized that we would camp, we would spend the night in a field full of leeches.

Immediately as we entered this area we were attacked by them. At first it was just one or two seen on the ground, then leaping onto our legs. Then we realized they were everywhere, like mosquitoes or flies or any insect that was a bother, but most insects that were a bother were familiar to us. The leech was not something with which we were familiar. And why was it so frightening, so strange? It was just a simple invertebrate, after all. But a leech is a different kind of invertebrate. To see it whirl itself around as it gathers momentum to fling itself dervishlike onto its victim is terrifying; to see the way it burrows into clothing as it tries to get next to a person's warm skin so it can first make a gash that cannot be felt, for it administers an anesthetic as it bites, is terrifying; to see a thin, steady stream of blood running down your arm or your companion's arm is terrifying, for the leech also administers in its bite an anticoagulant. Was it because it was silent, making no noise of any kind that made it so reprehensible, so shudder-making?

A leech,

just the mere words would make us jumpy, cross. When Dan had first told me of this journey, he had mentioned leeches as one of the disturbing things to be encountered. He had also mentioned altitude sickness and deprivations of everyday comforts such as showers, bathrooms, people you loved, but I remembered leeches more than I remembered Maoists, even when I got to Kathmandu and saw the evidence of a civil war, soldiers with submachine guns everywhere. I remember Dan saying that there will be leeches but we will have so much fun. That night above the Arun River, on the opposite side of the Barun River, looking into the Barun Valley, I was not concerned with anything but the leeches. And so when we walked into our campsite and I saw these little one-inch bugs whirling around and then leaping into the air and landing on us, my spine literally stiffened and curled. I could feel it do this, stiffen and then curl. I screamed loudly and silently at the same time. And then I did what everybody else was doing, Sherpa, porter, and fellow botanist, I forged ahead, grimaced, laughed, searched for the parasites, found them, and picked them off and killed them with great effort and satisfaction. Even so, the disdain and unhappiness for spending the night in a field of leeches never went away.

The stoves were lit and Cook began to make us food. There was no room for our dining tent so the table and chairs were set out on a tarpaulin. We had tea and biscuits, nothing could stop thisâand how grateful we were for this. Night fell suddenly, as if someone, somewhere, decided to turn out the light because it suited them right then. After being hot all day, suddenly we were cold and wanted very much to put on our warm clothes. But the clothes were way down below. Sunam had gone back down to hurry up the porters who were carrying our suitcases. The laxness of the porters made Dan and Bleddyn annoyed not only because they couldn't change into dry clothes but also because they wanted to review their collections of the day, try to do some cleaning of seeds, and make some entrances into the collection diaries. We were sitting on our chairs in the open air and looking out on the Barun Valley at night in the Himalaya. It was beautiful. But the leeches kept coming at us. Finally we set up a sort of Leech Patrol; each person, the four travelers, looking for leeches in four different directions.

Our luggage still had not arrived and there was much discussion regarding what the porters had been up to all day. And there was no

chang,

a fermented beverage made from millet, or any other kind of alcoholic beverage as far as we could tell, in the Maoist area. WeâI, reallyâfelt small, as if I were a toy, inside the bottom of a small bowl looking up at the rim and wondering what was beyond. The person who lived in a small village in Vermont was not lost to me, the person who existed before that was not lost to me. I was sitting six thousand feet or so up on a clearing we had made on the side of a foothill in the Himalaya. Only in the Himalaya would such a height be called a foothill. Everywhere else this height is a mountain. But from where we sat, we were at the bottomâfor we could see other risings high above us, from every direction a higher horizon. The moon came up, full and bright. And it looked like another moon, a moon I was not familiar with. Its light was so pure somehow, as if it didn't shine everywhere in the world; it seemed a moon that shone only here, above us. It sailed across the way, the skyway, that is, majestically, seemingly willful, on its own, not concerned with having a place in the rest of any natural scheme. It was a clear night. We sat on the tarpaulin, on the chairs around the table in a circle, huddled toward the middle to see more clearly and readily the leeches. We were looking up at the sky, clear and full of stars, the light from the moon outlining the tops of the higher hills, and they

were

hills when placed in context of the true risings beyond which we could not see.

It must have been near nine o'clock when we had our dinner. I should have been hungry but I wasn't. I felt sick, my stomach hurt, I wanted to throw up. I was served but could not eat. Dan said that perhaps it was the altitude. We were up at about six thousand feet. Dan flossed and brushed his teeth. I did not. I don't know what Sue and Bleddyn did. Dan and I went into our tent. He reminded me to check my shoes and socks for leeches, to check myself for leeches, to check the space around my sleeping bag for leeches. All was clear and then we settled in to have our nightly review of the day's events, which mostly resulted in huge cackling and laughter. We had finished our cackling and laughter and were about to go to sleep when there occurred a huge storm of fierce thunder and big rainâthe kind of thunder and rain that made me think it was pretending to be so fierce and then I thought it was the end of the world, we would never leave this place, the storm would so change the world that we would be forced to stay in the leech field in our tents forever And it reminded me that this was my first question when confronted with the landscape of the Himalaya: Is this real? It is real enough. We heard Bleddyn calling out to us, Dan and me, that we should check our tent window. Dan and I turned on our flashlights and saw an army of leeches trying to penetrate the window, a square made of mesh netting which served as ventilation on the side of our tent. It was horrifying, not only because we were so far away from everything that was familiar to us. All day as we had marched along, taking a new route to escape the Maoists and their demands, which we felt might include our very lives; we felt endangered, assaulted, scared. In reality it was just about a dozen leeches, but how to explain to a leech that we did not like President Powell? How to tell a Maoist that Powell wasn't even the president? At some point I stopped making a distinction between the Maoists and the leeches, at some point they became indistinguishable to me, but this was only to me. Fortunately I had acquired some

DEET

, against Dan's advice, that justifiably denounced insecticide, and I always carried it with me. I reached into my day pack, which was at the foot of my sleeping bag, and sprayed it furiously on the leeches trying to get into our tent and they just fell away and I hoped they were dead. I could not sleep. I wanted desperately to pee but when I thought of the leeches leaping up and then burrowing themselves in my pubic hair, I decided to hold it in. But then I couldn't fall asleep and so I went out of our tent, just outside the entrance, and took a long piss. This was a violation of some kind: you cannot take a long piss just outside your tent; you are not to make your traveling companions aware of the actual workings of your body. Not to allow anyone an awareness of the workings of your body is easy to do in our normal lives, where we have access to our own bathrooms, thirty-minute showers of water at a temperature that pleases us, toilets that allow their contents to disappear so completely that to ask where to could be made to seem a case of mental illness. After I had my pee, I took another sleeping pill and went to sleep and did not dream about Maoists, leeches, or anything else. And then I was awakened by a terrifying sound of land falling down from a great height, an avalanche. It sounded quite close by. The morning didn't come soon enough. We got dressed rapidly (I did not brush my teeth), packed up, ate, checked ourselves for leeches, and left. We never wanted to see that place again.

We got going without regret, without looking back, without even wishing for another moon like the one we had seen the night before. It was the most beautiful moon I had ever seen without a doubt, but I would not spend a night in a field full of leeches just to see another one like it. We marched upward the steep climb to the top. Many times the thick growth of maple, oak,

Sorbus,

and yew would thin out and clear up and I felt the top was near, but this clearing was only a pause leading up to more thick forests and darkness and moistness and slippery paths, almost falling down in a way that could be dangerousâand this was not a place to have an accident of any kind. To twist your ankle here wouldn't be good at all; it would cause much misery and inconvenience. Then again, if your heart cracked out here, how much longed-for would a twisted ankle be? We climbed up to nine thousand feet, finally reaching a clearing that was somewhat level. We were at the very top of the ridge of the mountain we had just walked up. Almost as a reward, Dan immediately found a

Cardiocrinum giganteum

that was almost twice as big as the tallest of us, and that was Dan himself. It had lots and lots of seed. How happy he was and Bleddyn too. And after that we seemed to find nothing but

Cardiocrinum giganteum,

they were everywhere. I remained deeply in the experience of the night before: The Moon, The Leeches, The Landslides, The Escape from the Maoists, all of it capitalized. We walked down the forested hillside, plunging into a gulley, going more steeply down it seemed than we had gone up the day before; the sun hot overhead, the sky clear of clouds and blue as if it had never known otherwise. Down we went, toward the Arun again, passing through a thick forest of oak,

Aralia,

and

Berberis.

I kept my eyes peeled to the ground, carefully picking out each step I took, for we were on moist ground. In fact the earth seemed to be only a leaky surface; I could hear water trickling, I could feel my feet slipping on the sticky wet ground. From time to time I fell and cursed myself for doing so. But then we were out in the open sun and the ground was dry and we were walking in nothing but red-fruited

Berberis.

But I couldn't collect any seeds because they are on the list of banned seeds, seeds not to be brought into my country. As usual, our destination seemed farther away the closer we got to it. We could see a village high above the other side of the Arun, and it was the village beyond that was our destination. We stopped for lunch just before crossing a river, that fed into the Arun, at a place called Sampung, and then one hour after lunch crossed the Arun and started climbing up again. That day after the night spent in the field with the leeches, we walked for nine hours and stopped in Chepuwa just a mile or two from our destination, the village of Chyamtang, because it was getting dark. We were so very tired and cross, though not with each other and not with the people who were taking care of us.