Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (16 page)

Hitler’s order for total radio silence among the attack formations had been followed, thus depriving Bletchley Park analysts of a clear picture through

Ultra

material. Regrettably, SHAEF relied far too much on Ultra intelligence, and tended to think that it was the fount of all knowledge. On 26 October, however, it had alighted upon

‘Hitler’s orders for setting up

a special force for special undertaking in west. Knowledge of English and American idiom essential for volunteers.’ And on 10 December, it worked out that radio silence had been imposed on all SS formations, which should have rung an alarm bell at SHAEF.

Unlike the German army the Luftwaffe had once again been incredibly lax, but SHAEF does not appear to have reacted to Bletchley transcripts. Already on 4 September, the Japanese ambassador in Berlin had reported after interviews with Ribbentrop and Hitler that the Germans were planning an offensive in the west in November

‘as soon as replenishing of air force was concluded’

. The subsequent inquiry into the intelligence failure stated,

‘The GAF [Luftwaffe] evidence shows

that ever since the last week in October, preparations have been in train to bring the bulk of the Luftwaffe on to airfields in the West.’

On 31 October, ‘J[agd]G[eschwader] 26 quoted Goering order that re-equipment of all fighter aircraft as fighter bombers must be possible within 24 hours.’ This was significant because it could certainly indicate preparations for an attack in support of ground troops. And on 14 November, Bletchley noted: ‘Fighter units in West not to use Geschwader badges or unit markings’. On 1 December, they read that courses for National Socialist Leadership Officers had been cancelled owing to ‘impending special operation’. The Nazi over-use of the word ‘special’ was probably the reason why this was not seized on. And on 3 December, a report was called for by Luftflotte Reich ‘on measures taken for technical supply of units that had arrived for operations in the west’. The next day fighter commanders were summoned to a conference at the headquarters of Jagdkorps II. Soon after, the whole of SG 4, a specialized ground-attack Geschwader, was transferred to the west from the eastern front. That should have raised some eyebrows.

The head of the Secret Intelligence Service considered it

‘a little startling

to find that the Germans had a better knowledge of the US order of battle from their signals intelligence than we had of the German order of battle from Source [Ultra]’. The reason was clear in his view.

‘Ever since

D-Day, US signals have been of great assistance to the enemy. It has been emphasized that, out of thirty odd US divisions in the west, the Germans have constantly known the locations, and often the intentions, of all but two or three. They knew that the southern wing of US First Army, on a front of about eighty miles, was mostly held either by new or by tired divisions.’

The understandably tired 4th and 28th Infantry Divisions were licking their wounds after the horrors of the Hürtgen Forest. They had been

sent to rest in the southern Ardennes, a steeply sloped area known as the ‘Luxembourg Switzerland’, and described as a

‘quiet paradise for weary troops’

. It seemed to be the least likely sector for an attack. The men were billeted in houses, to make a change from the extreme discomforts of foxholes in the Hürtgen Forest.

In the rear areas, soldiers and mechanics settled down with local families, and the shops were stocked with US Army produce.

‘The steady traffic

and the slush soon gave nearly every village the same drab, mud-splashed touch. In most of the drinking and eating places the atmosphere was that of some far western town of the movies where the men gathered at night to spice their lives with liquor. These soldiers, for the most part, had made their deal with the army. They didn’t care for the life, but they proposed to make the best of it.’

The Germans, despite all orders forbidding reconnaissance, had a very clear picture of certain sectors of the front, especially those which were lightly held, such as the 4th Infantry Division frontage in the south. German civilians could move back and forth, slipping between outposts along the River Sauer. The Germans were thus able to identify observation posts and gun positions. Counter-battery fire was an essential part of their plan to protect their pontoon bridges over the Sauer in the first vital hours of the attack. Some of the more experienced agents even mingled with off-duty American soldiers in villages behind the lines. After a few beers, many soldiers were happy to chat with Luxembourgers and Belgians who spoke a little English.

Locals ready to converse were rather fewer than before. The joy of liberation in September and initial American generosity had turned sour later in the autumn as collaborators were denounced and suspicions increased between Walloon and German-speaking communities. Resistance groups made increasingly unjustifiable demands for food and supplies from farmers. But, for the eastern cantons closest to the fighting along the Siegfried Line, the greatest dismay was caused by the decision of the American civil affairs administration to evacuate the majority of civilians between 5 and 9 October. Only a small picked number would be allowed to remain in each village to look after livestock. In one way, this would prove to be a mercy because even more farming families would have been killed otherwise.

Over the previous 150 years, the border areas of Eupen and St Vith had

moved back and forth between France, Prussia, Belgium and Germany, depending on the fortunes of war. In the Belgian elections of April 1939, more than 45 per cent of those in the mainly German-speaking ‘eastern cantons’ voted for the Heimattreue Front

which wanted the area reincorporated into the Reich. But by 1944 the privilege of belonging to the Reich had turned bitter. The German-speakers of the eastern cantons had found themselves treated as second-class citizens, jokingly known as

Rucksackdeutsche

who had been gathered up and carried along after the Ardennes invasion of 1940. And so many of their young men had been killed or crippled on the eastern front that now most German-speakers longed for liberation by the Reich’s enemies. Yet there were enough left still loyal to the Third Reich to constitute a considerable pool of potential informers and spies for German intelligence, known as

Frontläufer

.

Parties from the divisions in the Ardennes were allowed back to the VIII Corps rest camp at Arlon or to Bastogne, where Marlene Dietrich went to perform for the GIs, crooning huskily in her long sequinned gown which was so close-fitting that she wore no underwear. She nearly always sang ‘Lili Marlene’. Its lilting refrain had gripped the hearts of Allied troops, despite its German provenance.

‘The bloody Heinies!’

wrote one American soldier. ‘When they weren’t killing you they were making you cry.’

Dietrich loved the response of the soldiers, but she was much less enamoured of the staff officers she had to deal with.

‘La Dietrich was bitching,’

Hansen wrote in his diary. ‘Her trip among the corps of the First Army had been a rigorous one. She didn’t like the First Army. She didn’t like the competition between corps, armies and divisions. Most of all she disliked the colonels and generals of Eagle Main [12th Army Group rear headquarters] at Verdun where she lived on salmon because her meal times did not correspond to the chow periods and no one took an interest in her.’ She also claimed that she caught lice, but that did not stop her from accepting General Bradley’s invitation to cocktails, dinner ‘and a bad movie’ at the Hôtel Alfa in Luxembourg. General Patton, whom she claimed to have slept with, was clearly much more her sort of general. ‘Patton believes earnestly in a warrior’s Valhalla,’ Hansen also observed that day.

On the evening of Sunday 10 December, there was a heavy fall of snow. The next morning, Bradley, now partially recovered, went to Spa to see Hodges and Simpson. It would be their last meeting for some time. He returned in the afternoon after a long drive past Bastogne.

Snow covered the whole area and the roads were thick with slush as a result of the blizzard the previous night. A pair of shotguns which he had ordered were waiting for him. General Hodges seemed to have had the same idea. Three days later, he spent

‘a good part of the afternoon’

with Monsieur Francotte, a renowned gunmaker in Liège, ordering a shotgun to be made to his specifications.

Bradley’s headquarters remained quietly optimistic about the immediate future. That week staff officers concluded:

‘It is now certain that attrition

is steadily sapping the strength of German forces on the western front and that the crust of defence is thinner, more brittle and more vulnerable than it appears on our G-2 maps or to the troops in the line.’ Bradley’s chief worry was the replacement situation. His 12th Army Group was short of 17,581 men, and he planned to see Eisenhower about it in Versailles.

At a press conference on 15 December to praise the IX Tactical Air Command, Bradley estimated that the Germans had no more than six to seven hundred tanks along the whole front.

‘We think he is spread pretty thin all along,’

he said. Hansen noted that as far as air support was concerned, ‘Little doing today … Weather prevents their being operational even a quarter of the time.’ The bad visibility to prevent flying, which Hitler had so earnestly desired, was repeated day after day. It does not, however, appear to have hampered artillery-spotting aircraft on unofficial business in the Ardennes. Bradley received complaints that

‘GI’s in their zest

for barbecued pork were hunting [wild] boar in low-flying cubs with Thompson submachine guns.’

Also on 15 December, the

G-3

operations officer at the daily SHAEF briefing said that there was nothing to report from the Ardennes sector. Field Marshal Montgomery asked General Eisenhower if he minded his going back to the United Kingdom the next week for Christmas. His chief of staff, General Freddie de Guingand, had just left that morning. With regrettable timing on the very eve of the German onslaught, Montgomery stated that the shortages of

‘German manpower, equipment

and resources precluded any offensive action on their part’. On the other hand, VIII Corps in the Ardennes reported troop movements to its front, with the arrival of fresh formations.

In the north of the VIII Corps sector, the newly arrived 106th Infantry Division had just taken over the positions of the 2nd Infantry

Division on a hogsback ridge of the Schnee Eifel.

‘My men were amazed

at the appearance of the men from the incoming unit,’ wrote a company commander in the 2nd Division. ‘They were equipped with the maze of equipment that only replacements fresh from the States would have dared to call their own. And horror of horrors, they were wearing neckties! Shades of General Patton!’

*

During the handover a regimental commander from the 2nd Division told Colonel Cavender of the 423rd Infantry:

‘It has been very quiet

up here and your men will learn the easy way.’ The experienced troops pulling out took all their stoves with them. The green newcomers had none to dry out socks, so many cases of trench foot soon developed in the damp snow.

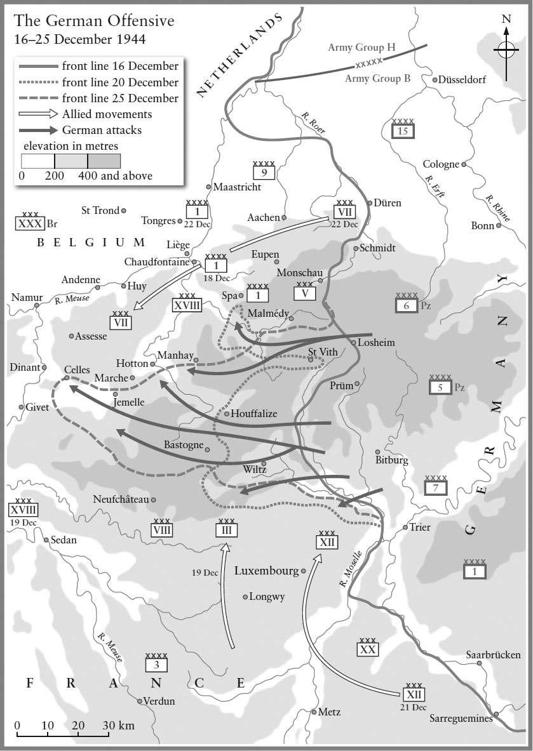

Over the following days the 106th Division heard tanks and other vehicles moving to their front, but their lack of experience made them unsure of what it meant. Even the experienced 4th Division to their south assumed that the engine noises came from one Volksgrenadier division being replaced by another. In fact there were seven panzer and thirteen infantry divisions in the first wave alone, coiled ready for the attack in the dark pinewoods ahead.

In Waffen-SS units especially, the excitement and impatience were clearly intense. A member of the 12th SS Panzer-Division

Hitler Jugend

wrote to his sister on the eve of battle.

‘Dear Ruth

, My daily letter will be very short today – short and sweet. I write during one of the great hours before an attack – full of unrest, full of expectation for what the next days will bring. Everyone who has been here the last two days and nights (especially nights), who has witnessed hour after hour the assembly of our crack divisions, who has heard the constant rattling of Panzers, knows that something is up and we are looking forward to a clear order to reduce the tension. We are still in the dark as to “where” and “how” but that cannot be helped! It is enough to know that we attack, and will throw the enemy from our homeland. That is a holy task!’ On the back of the sealed envelope he added a hurried postscript: ‘Ruth! Ruth! Ruth! WE MARCH!!!’ That must have been scribbled as they moved out, for the letter fell into American hands during the battle.